If you were a fellow in the 1950s, as you paused before repairing a leaky faucet, retrieving a bolt you just dropped down your Studebaker’s intake manifold, or tearing into a new addition on your split-level, you might have fetched yourself a copy of Popular Science magazine to check your method and approach.

In the era between WWl and VietNam, Pop Sci bestrode the middleclass/middlebrow world of handy- and would-be-handymen like a Colossus- it sought to instruct and explain, in sometimes breezy, often earnest and occasionally dire fashion, the scientific and mechanical goings-on of a world in flux. Sawdust covered stacks of Pop Sci were typically found in basement workshops, their pages rife with photos and drawings of fellows with pipes clamped between their teeth building go-karts and kitchens and cyclotrons, or fabulously elaborate cutaways of manufacturing plants or warships.

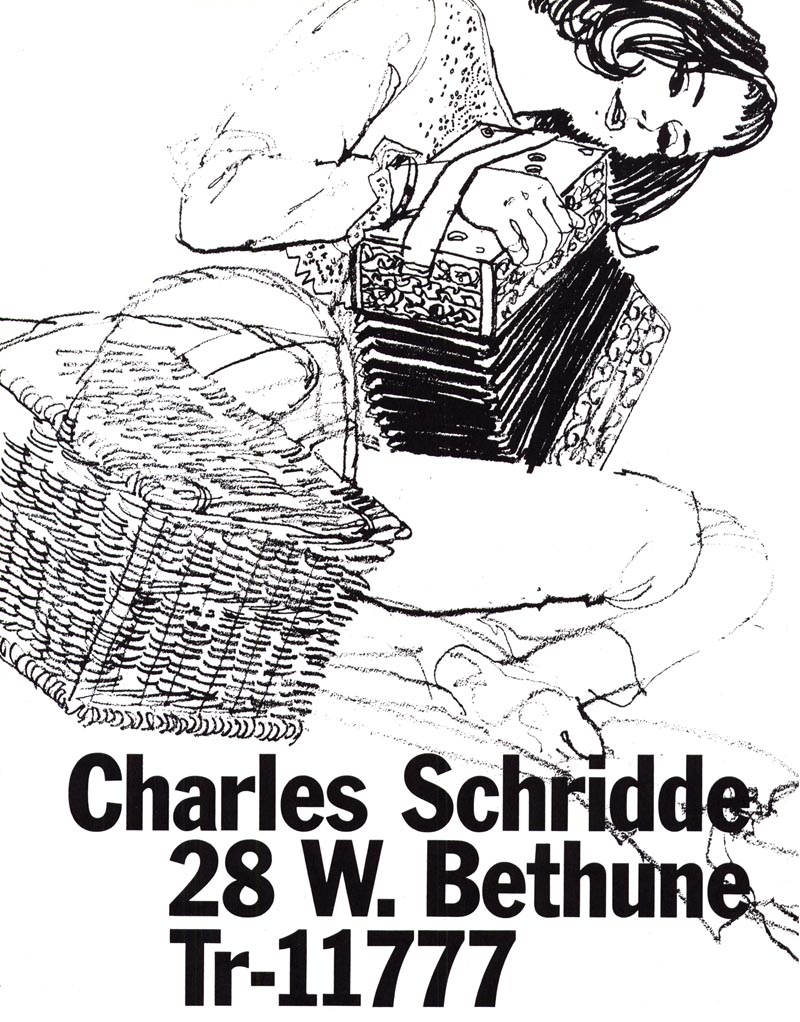

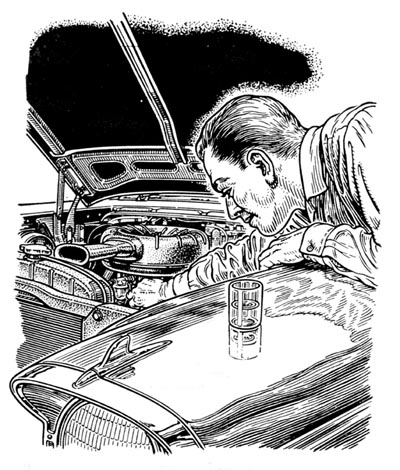

A monthly feature of Pop Sci was ‘Hints from the Model Garage’, a two-page spread of automotive hints and tips. From perhaps ’49 to ’62, it was illustrated by a man who signed his work “Rouse”. No further credit accompanied his eight panels each month, nor am I even certain of his first name, but for the sake of this article let’s call him “Art”.

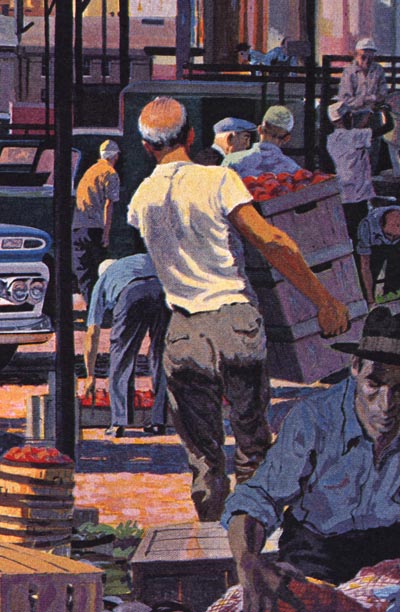

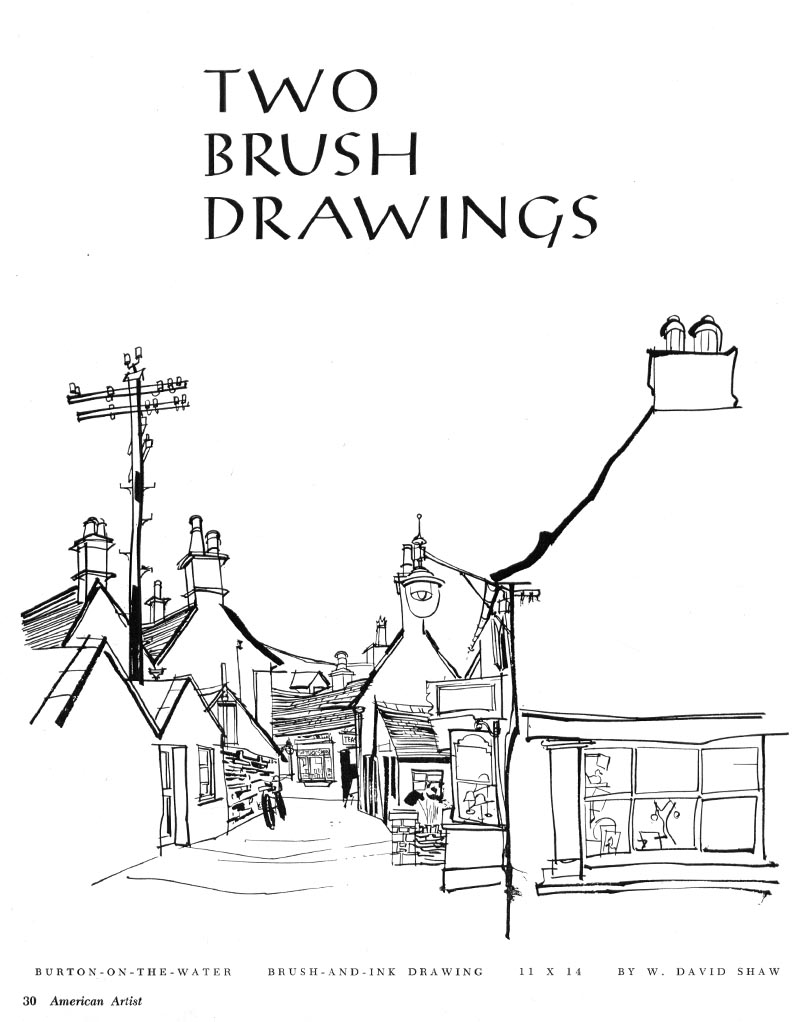

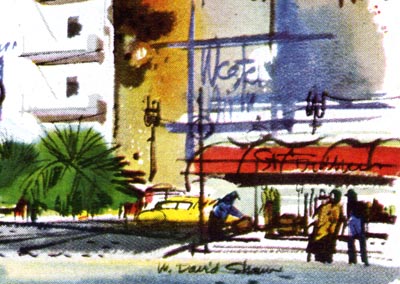

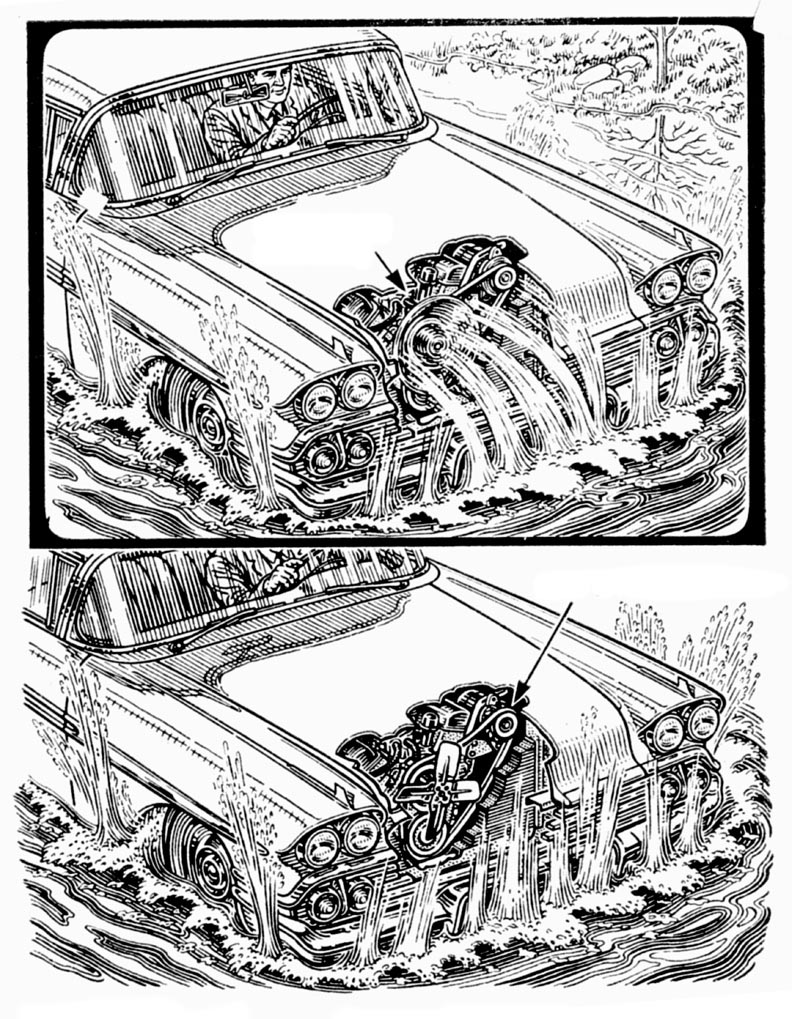

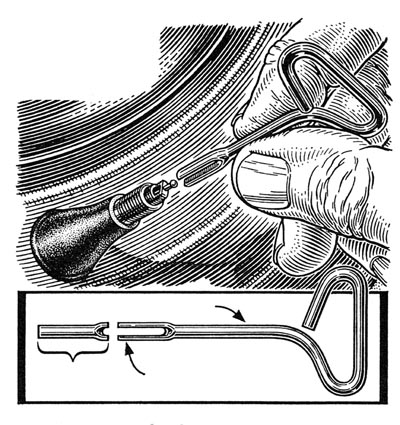

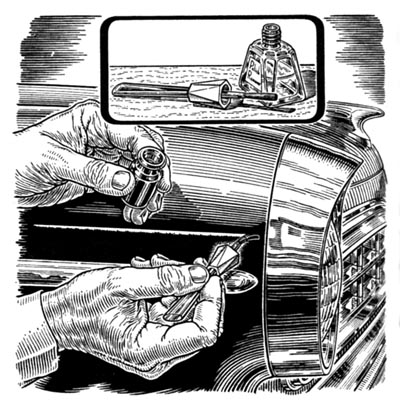

Rouse’s work goes far beyond the normal scope of technical illustration, which tends toward the dry and schematic: in addition to his precision he’s incredibly fluid, and shows signs of Horror Vacuii - there’s a graphomaniacal aspect to Rouse’s work which reminds me of Will Elder’s, sans the jokes.

Leif and I discussed the scratchboard look, but I’m convinced it’s done in ruling pen, crowquill and maybe a little tech pen, along with the aid of drafting equipment.

Bonafides in engineering or at least an intimate knowledge of how things work [and look] are explicit in Rouse’s rendering of ancillary parts and assemblies—it’s as if he can’t help himself; he must draw that windshield washer pump, and make it look great, even if the subject of the illustration is the carburetor.

Rouse’s manifestly dogged but lovely and complex approach—look at how not only the salient points of each illo but also the background details are fully fleshed out in sparkling detail—seem to suggest a man unafraid of sheer hard work in pursuit of his paycheck, and one who finds some delight in the dry corners of a niche of illustration which is normally carried out with little more than a purely factual approach.

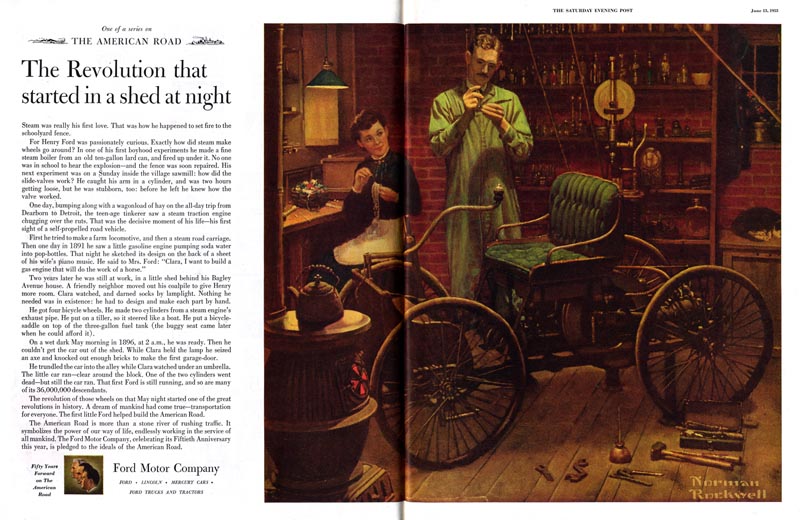

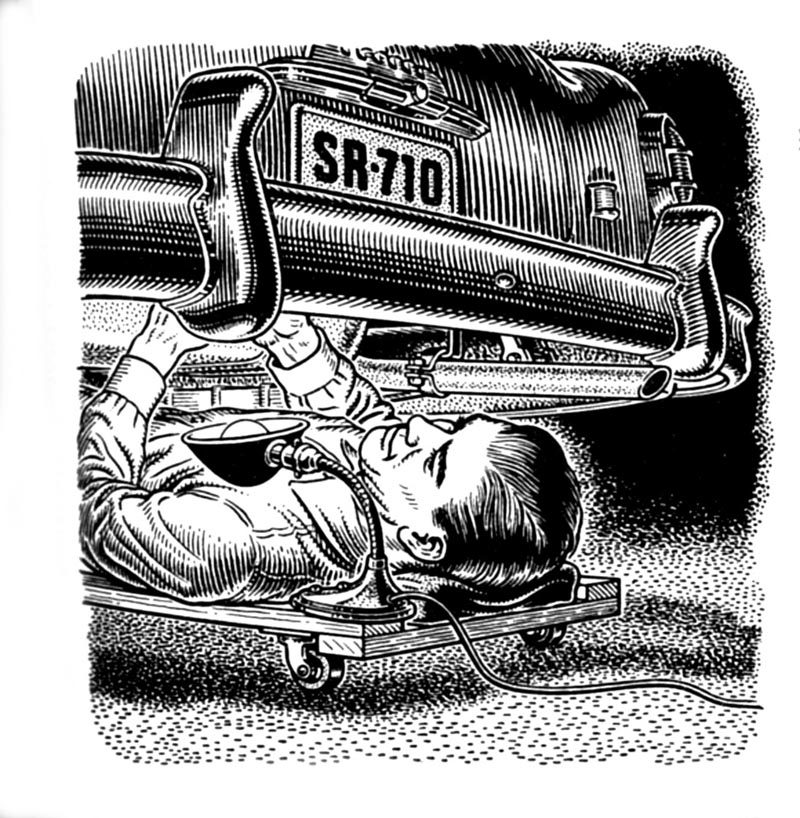

None of this professional detachment for Rouse—he’s the Norman Rockwell of down-and-dirty tech illustration. From his rendering of faces, I get the hint that his instructive time took place in the ‘20s:

the guy under the car looks like F. Scott Fitzgerald to me, and overall the penwork has the enthusiasm and skillfully graceful modeling of Charles Dana Gibson, if far more rigidly applied.

I can’t help but think that Rouse, upon entering the studio for the day or evening, didn’t sigh and mutter, “Dear God, not another carburetor,” but instead brought to the board some kind of affection for the mundane mechanical subjects of his talents, and in doing so left behind some modestly astonishing examples of inspired hard work.

[I have been unable to find even a shred of information on Rouse the man, so any help readers can provide would be appreciated.]

Many thanks to Dan for his insightful remarks and for sharing these images from his collection!