My friend and fellow in-house storyboard artist at O&M Toronto, Dan Milligan, had been asked by one of the AD's at the agency who also taught at OCAD to substitute teach her interpretive illustration class for a few weeks while she was out of the country. Because it was a large group, the AD had also asked her friend, Anita Kunz, to co-teach the class with Dan.

But when Dan and Anita presented themselves to the students for the first time, and it was suggested that half the group go with Dan and the other half go with Anita, what should have been a simple arrangement turned into a huge conflict.

Apart from a tiny handful of students, almost everyone began stampeding towards Anita.

Now you could rationalize that given the choice between a (then) unknown storyboard artist or an award winning 'celebrity' illustrator you would have rushed Anita with the rest of the group. But personally, I think something else was going on (and the comments Dan endured from the students who grudgingly joined his group in the end confirm my suspicions):

Nobody could imagine enjoying an advertising assignment. They all wanted to express their unfettered creativity - and presumed that Anita's group, doing an editorial assignment, would allow for limitless personal expression.

I believe you can trace the origin of this philosophical rift to the work of the first generation of 'Avant-gardes'... and the early adopter art directors who hired them.

Yesterday David Apatoff commented that Robert Weaver was tormented by the fact that he had had to "compromise" his creative vision by working as a an illustrator - in essence, as a 'hired gun' - and that there were some fellow illustrators who were sympathetic to that perspective.

This way of looking at the profession seems to me to have been entirely alien to the previous generation of illustrators. From what I've read and from the conversations I've had with those who were there, the goal of just about every art student was to get paid to draw (not a bad prospect) and exert as much creative influence as was possible, considering the collaborative nature of the commercial art business.

Looking at the editorial - or 'story' - art of the 50's, there is a general sense of traditional, acceptable, well-crafted restraint to the work - even when the subject matter is volatile. Even the most forward thinking illustrators like Al Parker seemed to have set certain parameters... certain boundaries that simply could not be crossed.

But beginning with the Avant-gardes - and I would say continuing to this very day, the idea of having total creative freedom (and I'm going to go out on a limb and suggest, even freedom from the constraints of craft) has been seen by a faction within the illustration business as a more acceptable - and even nobler - attitude than the traditional approach to commercial art.

I'm hardly in a position to judge. Like I said at the beginning of the week, I like a lot of the work we're looking at in these posts, even though I have to admit that I don't neccessarily understand it. But in regards to the broader public (and ultimately, we are talking about work produced for consumtion by the general public), no doubt some would say, "why would I want to pay somebody all that money for something my 5-year-old could draw?"

Is this were unfettered creativity leads? And if so, how does it make for viable commercial art?

This post will be continued... tomorrow.

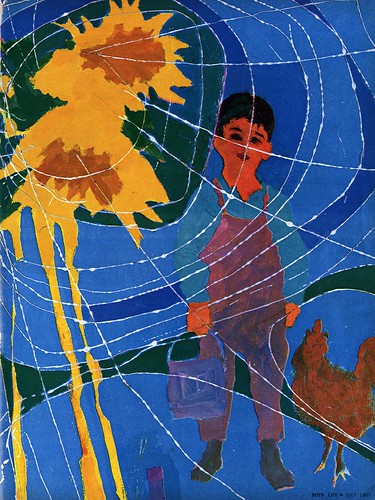

I certainly can't comment from "inside" the philosophical problem, but I can comment as someone who was soaking this in at the time. Now it may be because I was young, but almost everything we are seeing here, I love. Especially the more expressive use of color. I remember long afternoons tearing through these magazines, pulling pages out (The rooster thing FOR SURE!)and taping them up in my room. So much of this seemed an outgrowth of social changes of the time. More permissive with the use of color, design, ideas led to the rift here. What was the artist's responsibility/rights? I'm not sure, but hey it made for some amazing work. I love what we see here this week. It takes me back and inspires me.

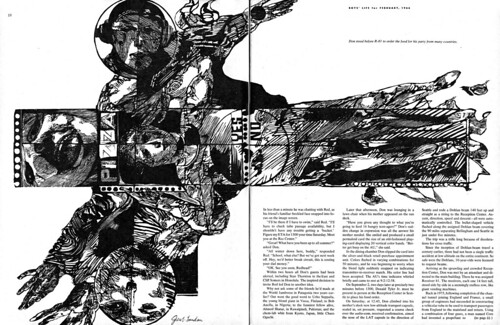

ReplyDeleteHi Leif, That'sa great era of really creative illustration. One of my very favorites of that time was Jacob Landau, do you remember his work ? He was fantastic. I have a magazine somewhere in which he did all of the illustrations. If, and when i find it, I'll send you scans.

ReplyDeleteLeif -

ReplyDeleteThank you SO much for this blog! It really is an inspiration and education, and I love reading it (almost) every day.

I cannot recall how or when, but I've had Mr. Milligan's site bookmarked on my browser for some time now... he and Anita are both fantabulous artists. Great story!

The great illustrators of the golden age knew the difference between what they camera did and what they did. This is why in Pyle's lecture notes he castigates a student for not having a model to work from because they shouldn't need models. Their province is the imagination, the depths. Dunn said similar things in his lecture notes. F.R.Gruger said, "Illustration can't hope to compete with the camera in the reporting of facts. (Illustration) has nobusiness with the outer shells of things at all. It deals with the spirit"

ReplyDeleteWhile the work of the golden show clear evidence they were making art and not clicking a shutter to capture reality, the economics and harsh realities of the depression and dull editors made the point moot.

From that point on, more and more of the attempt was to make the interiors of the magazine "pop" more. Thus large outlined shapes of strong color. Luckily great talents like Al Parker could take that limitation (all freedoms result in limitations after all, that's the yin and the yang of it)and still make beautiful work.

The other point in all this is the political idea that fantasy and enjoyment are Tory ideas that the bohemian artist, struggling along with the rest of the huddled masses, should be opposed to and should actively seek to destroy for the sake of the common good. Social Realism for social awareness leading to social change...

The fact that Art is entertaining by nature, of course, makes this oppositional stance, self defeating. And the fact that Dunn and Pyle and Wyeth and Coll and Gruger were full up with humanity and life-enriching "equipment for living" as Kenneth Burke calls Story. The greats had heart to spare, for Tory and Dock Worker alike, a fact that seems to have been lost on the more politically minded.

These factors and many others, I think, account for so much doubt and confusion that occurred in the arts after the depression which culminated, in good ways and bad, in the 1960s.

I could be wrong, of course.

Kev Ferrara

The Dead Rider

Dark Horse Comics

You should be able to write a reaction paper at college. Here is https://paperovernight.com/blog/reaction-paper what you need!

ReplyDelete