I heartily agree. Unfortunately, 'life ain't like that'. Many people - many artists, art directors, clients - even the general public - place a value on artwork based on how they have personally chosen to categorized it. Which brings us to our second commentor who, in response to yesterday's post put it rather astutely: "The old joke used to be (still relevant I guess) is that the difference between an illustrator & a cartoonist was about $500..."

Since we are talking about commercial art (and the commercial artists who hope to make a living from their efforts) the perception of others regarding the merit of what exactly they are producing profoundly affects not only their fiscal bottom line, but their psychological one as well.

We can all learn a lot from the experience of others -- and that brings me to an enlightening anecdote from an artist we looked at not long ago: Tom Sawyer. I believe Tom has the sort of healthy attitude all artists - hell, all creative professionals - should strive for. This excerpt from Tom's memoirs perfectly (if you'll pardon the pun) illustrates the point:

"Largely out of curiosity I learned more and more about how the business side of advertising worked. Which resulted, I suppose inevitably, in my becoming something of a pain-in-the-ass at Johnstone & Cushing,"

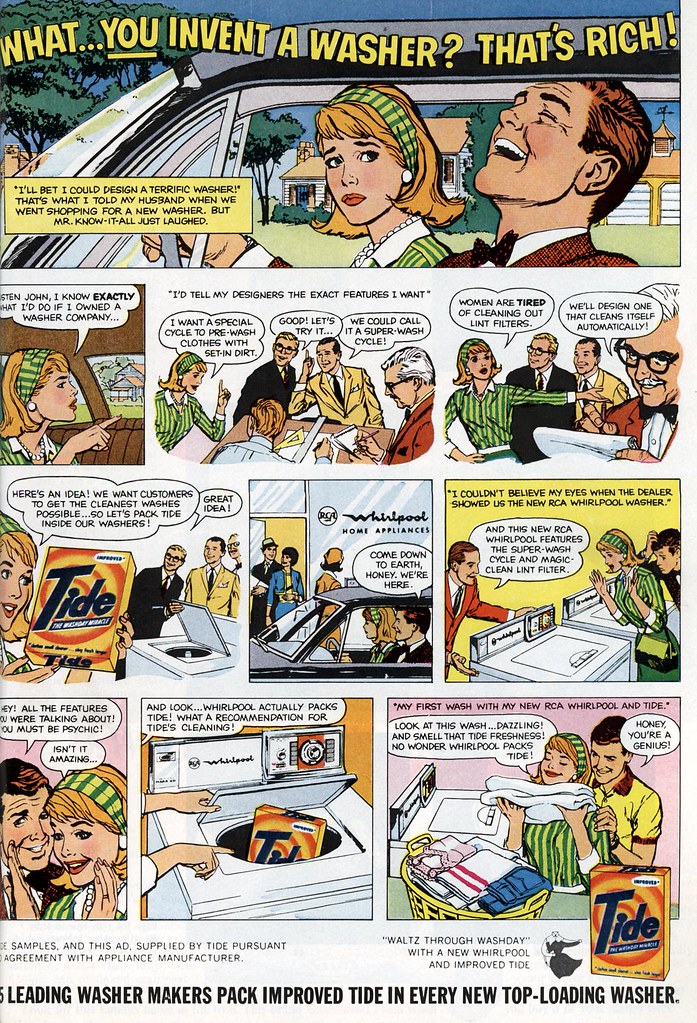

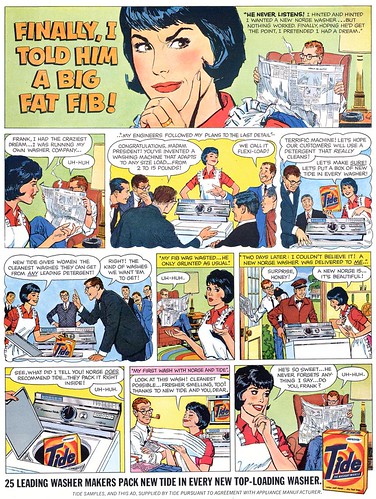

"... and eventually alienated me from the larger arena of cartoonists and illustrators in general. My first steps in that direction – more like a leap, actually – came via a dispute with J&C over an assignment to illustrate a comic-book style advertisement for Tide laundry detergent."

"Working in this form was not unusual – I had drawn dozens of similar jobs. But the difference here was that instead of this one being printed in the Sunday color-comics section of newspapers all over the country, it was intended as a full-page, four-color advertisement which would appear simultaneously in several slick women’s magazines, among them McCall’s, Ladies Home Journal and Good Housekeeping."

"A fresh venue for the comics format, it immediately struck me that in those publications it would be an attention-grabber – which of course is what advertising is all about. I asked Al Stenzel what the job would pay. Accustomed as he was to the docility, the seeming near-gratitude shown by most artists for being paid at all, he was put-off that I’d even inquired. Al shrugged, replying that it would of course be the then-going rate for the Sunday comics ads – $300 to $400."

"I told him that wasn’t acceptable, that it should be substantially higher. Which of course further annoyed him. Cranky, Al said he’d take it up with management, and I returned to my drawing table. And a few minutes later I was summoned to Jack Cushing’s office. Jack wasn’t happy, and wanted to know what my problem was.

I explained that my friends who were ‘real’ illustrators were paid $2,500 or more for advertisements in such magazines, some not even full-page ads, and that was what I expected to receive. Astonished – and offended – by such presumption, he reminded me that this was just ‘comics.’ "

I explained that my friends who were ‘real’ illustrators were paid $2,500 or more for advertisements in such magazines, some not even full-page ads, and that was what I expected to receive. Astonished – and offended – by such presumption, he reminded me that this was just ‘comics.’ ""I was astonished that he didn’t understand, much less that we were even discussing it. And a moment later I was further surprised to find myself explaining, to this man who was old enough to be my father, and a veteran of the trade, that we were talking a different, more upscale market, that the ad agency that had given him the job would, on behalf of its client, have to pay substantially more per pair of eyeballs for the space in those magazines than it would for newspaper insertion – the premium for reaching a far more targeted market – which, I reiterated, was why the illustrators were able to charge more."

"I likened it in one way to the rationale by which advertisers had to pay higher rates for commercial time on a hit network TV show or movie aimed at women than they would, say, for a local broadcast with a not-so-specialized audience."

"It was my first encounter with the phenomenon of the entrepreneur who, having invented a business – the box, if you will – around which things had changed, had become reluctant to revisit any of it, to ruminate outside of those parameters. And clearly, as a mere [schmuck] artist, I was about the last person Cushing expected to hear articulating any of it. His look gave me the impression that in his view, since I was a guy who spends his life at a drawing-table, I wasn’t supposed to know this stuff. And it pissed him off. Jack rather grumpily offered that he’d think about it."

"Next day, I had the assignment – at the then-unheard-of-for- Johnstone & Cushing price I’d demanded. Eventually I illustrated several such advertisements..."

*Once again, a reminder that Jim Amash conducted an excellent and very thorough interview with Tom Sawyer in Alter Ego #77, which is still available from the publisher.

All of this post's content from Tom's memoirs is Copyright © 2008 by Tom Sawyer Productions, Inc.

My Tom Sawyer Flickr set.

well, thats a discussion. anyway, nowadays it seems that you make more money in comic books that in illustrations. great post

ReplyDeleteThat's a fabulous story: How this clever man finally got what he wanted.

ReplyDeleteHis comics must have had some impact on all those housewifes...

This is why artists need to learn more about the business side. Tom was absolutely correct in his assessment.

ReplyDeleteFreelancers in general (and I'm thinking of the writing side in particular) tend to under-value their work, which leaves them open to exploitation.