"This field uses much the same type of talent employed by the syndicates," begins Rodewald, "but mostly on a free-lance instead of a salary basis."

"It is perhaps the lowest-paid field in the whole art business (twenty-five dollars for a whole page of four to six line drawings is not uncommon), and it is worth considering only as a refuge of desperation. A young beginner may glean a certain amount of valuable experience from this work; otherwise only an artist of phenominal speed or one who works on a royalty basis can hope to earn more than the barest subsistence."

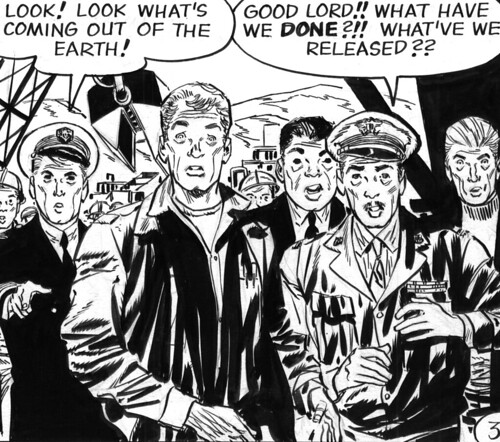

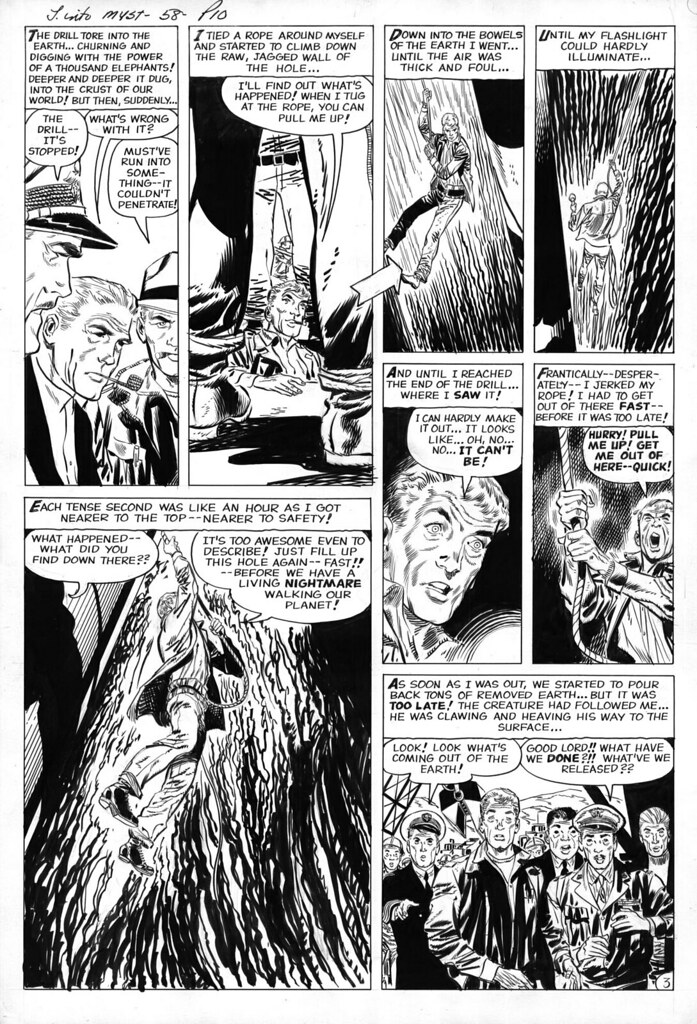

Its mind-boggling to think that an illustrator of the calibre of Don Heck, who drew the page above in 1959, would be willing to pour this much quality into work that paid only $25 per page. Jim Amash has interviewed over a hundred comic book professionals from the early days of the business for Alter Ego magazine and says, "almost all of them said they had wanted to get out of the business - if they could have. Some, like Jerry Robinson, tried showing their samples to editors in more lucrative markets like book and magazine publishing. But there was a stigma attached to the comics industry, and as soon as editors saw the samples were comic pages, they didn't care how good they were, they wanted nothing to do with you."

Some artists like Jack Kamen left the comic book business for exactly that reason. Kamen, who quit the comics the same year Fred Rodewald's article was published, found he could do similar style line drawings for advertising clients at $40 to $50 per drawing. In an interview in The Comics Journal #240, Kamen says he could walk into a New York ad agency, "and walk out with $1,500 worth of work. I'd say, 'What do you got for me?' 'Well, we've got 30 or 40 drawings over hear at $40-$50 bucks a piece.' 'I'll take it.' "

Ten years later, page rates in the comics business had only gone up about ten or fifteen dollars, and even then, the business was so unstable that they would sometimes drop down to as low as twenty dollars. Long-time industry veteran, John Romita Sr., described in a 2001 interview how the comics business of the late 50's/early 60's was "a roller-coaster."

"I remember going from $20 dollars a page, pencil and ink, to $40 a page, pencil and ink. And then, the next two years, every time I took a job in, I got a cut and I ended up at $20 a page again. We were flying without a parachute. I used to be afraid of getting a mortgage."

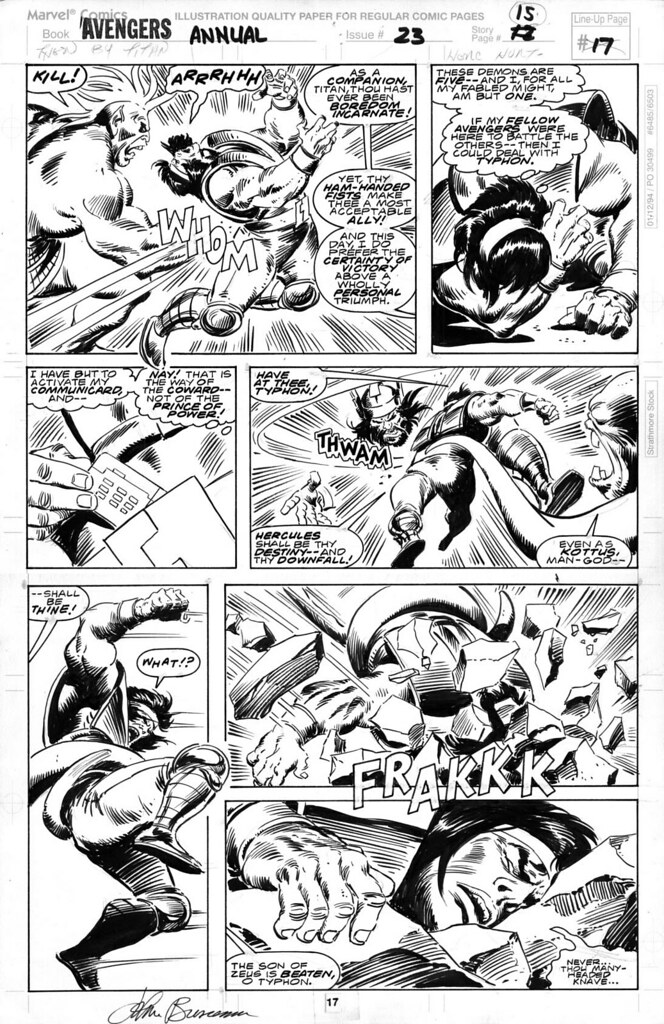

In spite of those stressful conditions, the business was able to attract some remarkable talents. John Buscema (above), undisputably one of the finest draftsmen the comics have ever seen, was working then at Fredman~Chaite studios as a storyboard artist.

In an interview published in Alter Ego #15, Buscema says, "Advertising's a brutal life, believe me. For example, I would work a whole week and get ready to go home on a Friday night, and I'd get a call - the owner of the studio would get a call from an agency, that there was a campaign that had to be in by Monday. You know, when you talk about a campaign, you're talking about dozens of artists working on one product. It could be cars, it could be cigarettes, it could be anything, and you'd have to stay in the city. I'd have to call my wife and tell her I wasn't going to be home for the weekend."

"So when I got the call from Marvel, [then Marvel editor-in-chief] Stan [Lee] said, 'I don't know if you'll agree to work, We'll make you happy, financially, and we have plenty of work' I never thought twice and I returned to comics."

By then it was the mid-60's and page rates for top talent had climbed to around $60, according to Jim Amash, who was quoted that number by one of the industry giants, Jack Kirby.

John Buscema drew on his advertising art acumen in his approach to his comics work. Reflecting Rodewald's advice that one must be incredibly fast to make a living in comics, Buscema once told a group of young professionals during a 'chalk-talk' tutorial, "Are you guys familiar with the one line? ... You put in three or four lines, I put in one. I did that in half, a third, a quarter of the time.... We picked that up in advertising. This is a very simplified way - its supposed to be very, very sketchy. But carried it over into comics. ... You guys want to struggle along with the pages, you want to fill in a black background... what's the point of filling in a whole black area when you can just scribble it in? ... Your problem is to tell a story the best possible way, the fastest possible way. ... Do your job. If you earn your own pay, that's it. You're in this for the money!"

I asked several industry professionals for a rough estimate of page rates typical of mainstream comics today. One artist, who has been out of the business for some time now, told me he was recently offered an assignment at $300 a page, pencils and inks. He told me, "That's about what the rate was in l980."

"When I was working in comics," he continued, "it was a decent living. With royalties you could expect to do fairly well on a monthly book. Just about everything else I've worked on as an artist has paid better- animation, storyboards, advertising...probably even signpainting if I had tried that."

Other artists confirmed this number, although noting that there are some working for less. However, said one pro with more than a decade of experience, "As long as you can be consistent and get things done (mostly) on time, it's more than possible [to make a living in comics]. There's also additional income from royalties (if you're on a book that sells well enough), trade paperbacks, and original art sales. I also do commission work through my art dealer. I'm not rich, by any measure, but I manage to pay all my bills on time and I haven't had to skip any meals yet."

"It's definitely not as lucrative as mainstream illustration work, but it's a hell of a lot more fun!"

And echoing that sentiment are these sage words from one long-time professional comic artist:

"I'm occasionally surprised how much, and how little, some artists are paid per page, but you can do well either way if you apply yourself to the work. If you get into a field or have a specific career based on the potential of making money you've lost already. Having a passion for what you do will always bring a monetary reward, some will become wealthy but most will have a very enjoyable life doing what they love to do, and that ain't bad, considering."

Nice article. I always like hearing these sorts of things in context to the time period.

ReplyDeleteSo what is $25 a page equivalent to in far as today's page rates?

I had the sheer joy of filming John Buscema for the Frazetta documentary. At the end of the interview he did a sketch for a book we were going to give to Frank at the end of filming.

Watching him start with a wrist, and sticking true to his "one-line" rule Conan emerged out of nowhere and we all gasped at the ease and proficiency of such seasoned skills.

He was sooo damn good.

=s=

people are still putting that much or more into pages for $25 or less.

ReplyDeleteYikes! never wanted to do comic books (especially the non-cartoony kind), and I'm too slow and deliberate anyways. Waaaaaaaay too slow.

ReplyDeleteThis is a sad story, but at least these fellas seem to enjoy their work.

Thanks again for another great presentation. These business posts have been fascinating.

Shane, I'm dying of envy that you had this amazing experience - you lucky bastard. How great that such a film exists... is it online somewhere? I'm out of the loop on this stuff, I'm afraid...

ReplyDeletemellon;

I hope you don't mean people working in the mainstream for major publishers are getting paid $25 a page, because if that's so, we're going to have to stage an intervention.

harley; thanks for your feedback - its good to know these posts were appreciated. Let's hope younger readers give what was presented this week some thoughtful consideration. Whatever career path they choose, these posts were intended to provide some historical context and some perspective on current opportunities.

Thanks for this post. I'm an art student studying illustration and I'm interested not only in comics, but also in animation, character design, and storyboards. How much of this article still applies to today? For me, as long as I have a job that pays me to draw (pays me enough to get my bills done and eat) I'm pretty happy. Keep in mind that I'm super naive, though. :D

ReplyDeleteThis comment has been removed by a blog administrator.

ReplyDeleteThere are a lot more comic companies out there now, so it's good for someone starting out, but there are smaller pay rates for everyone.

ReplyDeleteSeasoned pros who made a lot of money in the 90s can't get much comic work these days. Now the best paying work is in Advertising! Storyboards can be a easy job for someone used to doing comics.

I agree with Leif,about Shane

ReplyDelete"I'm dying of envy that you had this amazing experience"

Have you seen this.. John Buscema Drawing Capt. America and ink...

http://www.youtube.com/watch?v=bo4d8oTU2tk&feature=related

'Best

Atula

Fantastic article. Too many comics history stories concentrate on art styles, genres and characters ... without talking about the money. Thanks, thanks, thanks!

ReplyDelete$300 a page, pencils and inks. He told me, "That's about what the rate was in l980."

ReplyDeleteThats $216,000 a year in 1980. I would say thats pretty damn good.

Even King Kirby got $57,600 in 1966, pretty good for the time.

Yes theyn should've got a piece of the action but they were far from paupers. At least for the top guys.

$6k for a 20 page book. 72k a year. That's a white collar salary in 2019. In 1980 it's much more.

Deletegood useful content....

ReplyDelete