"Shortly after a plane landed at the airfield three miles from the internment centre, a dilapidated truck driven by two Japanese soldiers brought representatives from the camp. Most of the reception committee consisted of members of the Chefoo Boy Scout troop. With enthusiasm they quickly unloaded the plane and transferred the supplies to the truck."

"The former Mission, which incidentally was the birthplace of Henry R. Luce, the publisher of Life, was made up of a large number of solidly constructed brick buildings, surrounded by a high brick wall. The Japanese had built guard towers at strategic locations along this wall, which was topped with electrified barbed wire."

"Most of the families lived in long, one-story buildings divided into several rooms approximately nine by twelve feet. Each of these cubicles was ordinarily occupied by two or three people, a man and wife and perhaps a child. The blocks of buildings had a shanty-town look. Each dwelling had a tiny back yard equipped with an improvised stove, chairs and a table made from available junk, according to the resourcefulness of the tenant. Stovepipes were constructed by piecing together discarded tin cans [shown below]. Bricks, stones, crates, bamboo poles and metal containers were quickly put to use by those lucky enough to be able to find them. There were also a number of larger buildings."

"One was occupied by bachelor girls, another a men’s dormitory. Perhaps the grandest building was the hospital. It was excellently staffed by internees, among whom were some of the best doctors in North China. There was simple church, more than adequately attended to by the missionaries, who practically overran the camp."

"I climbed the wooden ladder in one of the guard towers and when I got to the top I found a somewhat embarrassed Jap sentry. When I greeted him with “Konnichi-wa”, he snapped to attention, saluted me and handed me his rifle. Naturally I was surprised, but I accepted the weapon, inspected it and handed it back to him. He again saluted and after returning his salute I descended the ladder, leaving him with mutual “sayonaras”. I felt that if it was as easy as that, I could certainly get him to pose for a sketch. The next day I made the painting of him in the tower which is reproduced on the third cover. That night I found a bottle of saki that he had left in my quarters as an expression of his gratitude."

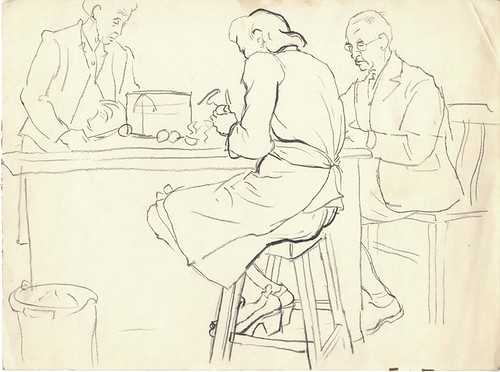

"Most of the prisoners were British. There were also Americans, Belgians, Italians, Eurasians and the various other types that would naturally be found in a group of people gathered under these circumstances from northern Chinese towns such as Tientsin, Peiping, Cheefoo and Tsingtao. They were missionaries, soldiers of fortune, businessmen, educators, professional people and scholars, such as E. T. C. Werner, author of many books on Chinese life, customs and mythology. There were the powerful and influential leaders of industry known as “taipans”. These people were accustomed to having servants and living in the luxury of the Occidental in the Orient. When they were all thrown together and forced to make their new home livable it required considerable readjustment. During the first few days of internment, they had the new experience of having to perform menial tasks before the eyes of Chinese coolies, who reclined under trees and watched their humiliation with great glee."

"A committee of nine selected by the internees took care of what self-government was permitted and of all negotiations with the Japanese authorities. They organized schools, set up kitchens, saw that the hospital was staffed, appointed fire tenders and organized games and dances. An orchestra was formed by an American Negro musician, who had come to China to play with a jazz band, a couple of Hawaiians and a few amateurs. They played a conglomeration of early vintage jazz tunes such as “Sweet Sue,” “Honeysuckle Rose,” “Red Sails in the Sunset,” and, after the liberation, “Happy Days Are Here Again.” Every able-bodied person was assigned some duty according to his special abilities. General welfare of the camp was gradually improved, and soon even shower rooms were constructed."

"The women, many of whom had never cooked and sewed before, showed considerable skill. The problem of making clothing last was one of their difficult tasks and they accomplished it amazingly well. One woman was a gifted interior decorator, and she and her husband made their small cubicle on of the wonders of the camp."

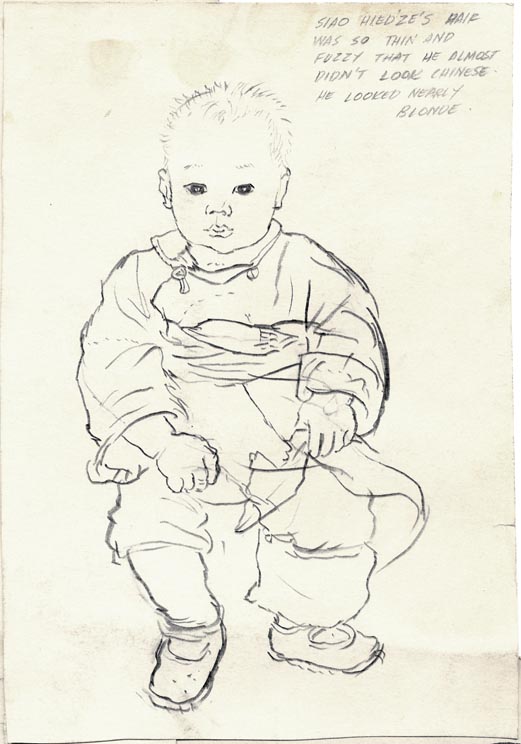

"The prisoners were not subject to beating, but infants and old people endured needless discomfort. Daily assemblies were enforced, and people made to stand in formations while they were counted. Bad weather and lack of adequate clothing made this a great hardship. Giving babies as well as adults nearing their ninetieth year a poor diet of rice gruel, turnips and bread, but almost entirely lacking in meat, eggs and dairy products, was unnecessarily inhumane. Located in a fertile and rich part of the Shantung peninsula, the camp could easily have been supplied with more and better food. By an “over-the-wall” black market the internees were able to augment their diet. Those who lacked cash to deal with the Chinese outside sold wedding rings and other personal treasures to individual Japanese guards for a fraction of their value. This black market was organized and run by a Catholic priest internee whose membership in the Trappist Order had prevented his speaking a word during the twenty-five years prior to his imprisonment. His efficiency and volubility were admired by fellow internees."

"Some of the people felt it important to buy black market whiskey as well as food. The ever-resourceful Chinese peasants supplied this demand with “bai gar” (white lightning), a horribly potent drink resembling vodka, but made from millet. If no other beverage is available, it might be recommended, but not very highly."

* My thanks to Kim Smith for providing both the art and article for this week's topic. Our story continues tomorrow.

Very good post for Veteran's Day, and what terrific draughtsmanship and brushwork. Thank you for showing us Smith's work.

ReplyDeleteFantastic. Beautiful sketches and a compelling story. I love the scene in which the Japanese soldier hands him - a prisoner - his weapon for inspection. Such a strange, human moment, oddly funny.

ReplyDelete