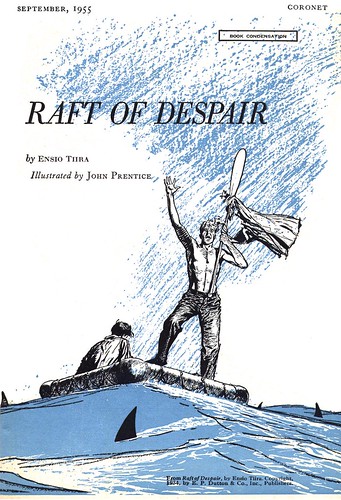

Some of Smith's illustrations (the few I'd seen) reminded me a little of Robert Fawcett's work. So I particularly enjoyed this anecdote Charlie related to me about meeting Robert Fawcett:

"May have told you this, but about 1950 or '51 Haines Hall and Chet Patterson asked me to join them for dinner one evening at one of those old but posh SF eateries. The lure, RF would be joining us. Believe Stan Galli and Bruce Bomberger were there too. With no warning, they sat me next to RF (Haines' brother-in-law). In a lull, I ventured a question to the great one....'Do you know William A. Smith?' He did a double take, turned to Haines, and gesturing to me, said, 'who's this?' I think his actual words were 'who the hell is this?' Haines explained ( I was the favored new kid on the block), and RF reluctantly turned and said, 'yes, Bill is a good friend....and he's a fine painter'. He did not say 'illustrator'. That was the only conversation from him for the evening, with me at least. At the time I naturally was in awe of RF, but was also an admirer of Wm. A. Smith."

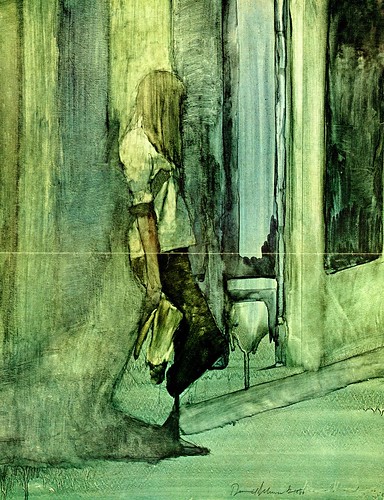

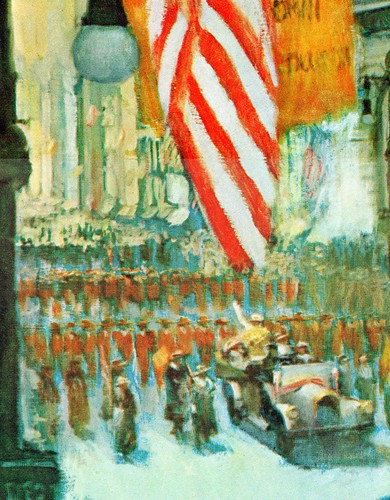

About these images, Charlie wrote:

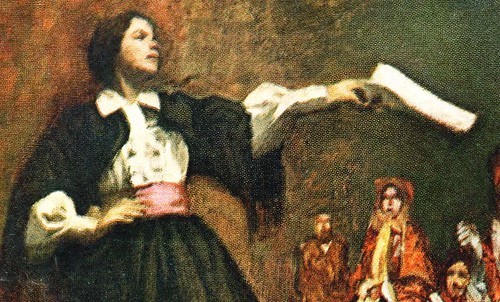

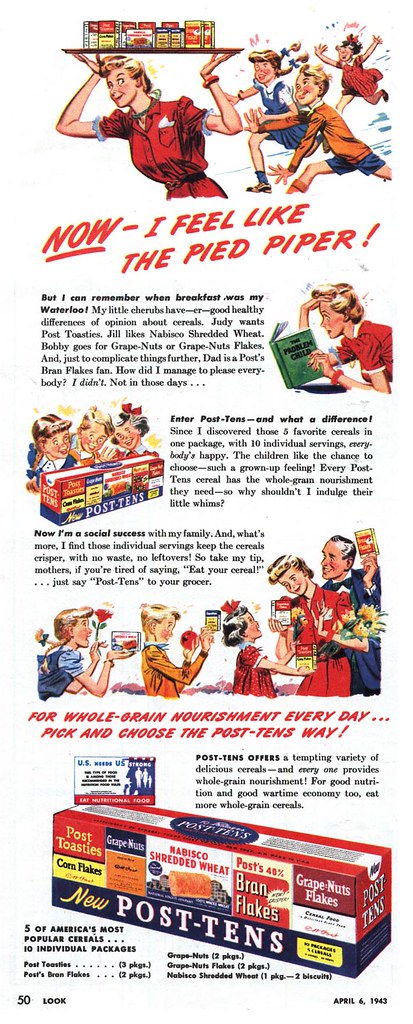

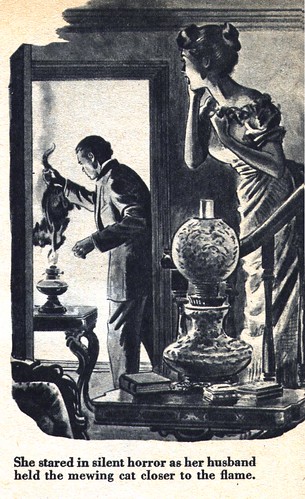

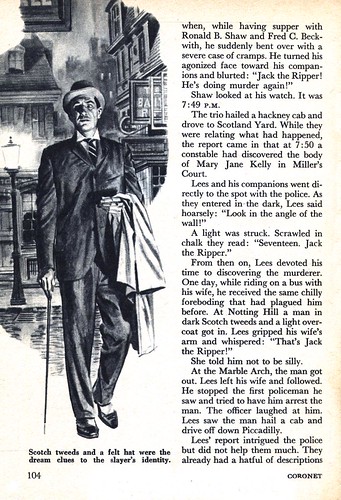

"Smith had a heavy painterly hand....but could be oh-so subtle when the character or scene needed it. I could tell he had to 'behave himself' on the Coca Cola ad [above] ...had to hold back some of that 'horsepower' he possessed. He was not as inventive in style and technique as, say, Briggs, Parker, Fawcett, etc.....but he was rock solid on dramatic presentation."

Charlie went on to say, "He seemed a mystery....never heard much about him or his career, etc." - which I was unable to help with, since what I knew about the artist was no more than what was available in the short bio you can find in Walt Reed's "Illustrator in America".

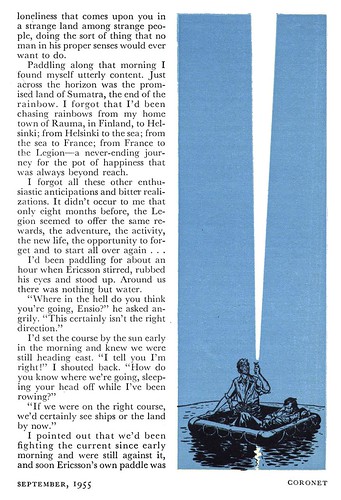

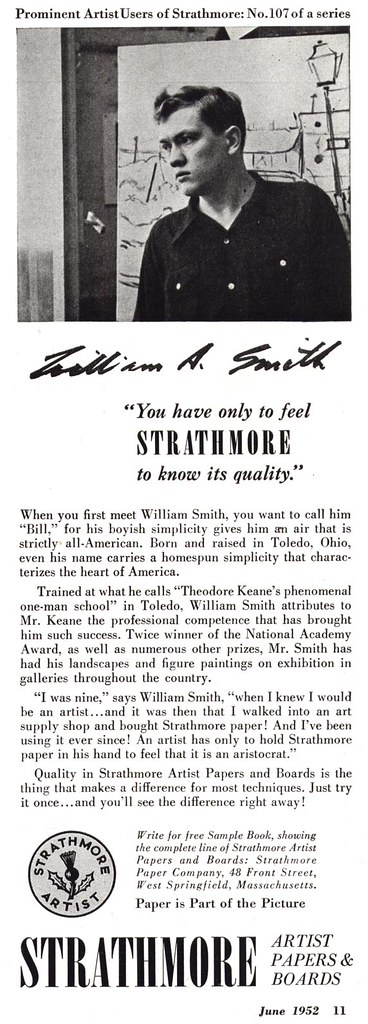

Then, in one of those coincidences that make me think "there are no coincidences", a package arrived in the mail: a recent acquisition from ebay... two bound volumes of American Artist magazine, 1952 and 1953. And what should the June 1952 issue contain but a six-page article on William A. Smith!

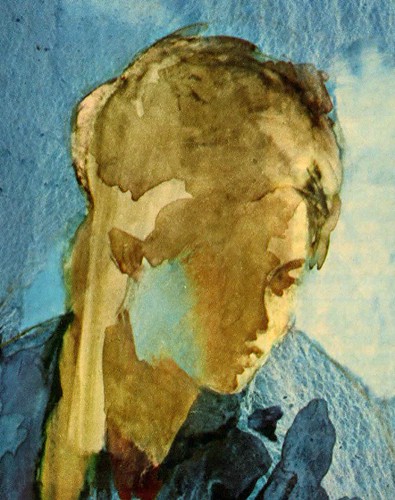

That same issue contained this ad below, so now you know what the artist looked like around the time he painted these pieces.

With the generous assistance of Charlie Allen, who has provided virtually all the scans I'll be presenting, and with the benefit of the information in the American Artist article, it looks like we will get to spend this week learning about "a fine painter", William A. Smith.