There followed some years of varied work doing anything that came to hand, including book illustration and movie posters for Fox films. It was a period of discouragement, for Briggs considered himself a failure after a brilliant beginning. But it was also a period of self-appraisal and criticism; an eventually healthy interlude that lead to better things.

He was merciless in his scrutiny of himself. "I realized that I just wasn't doing acceptable work, because if it had been good, they would have wanted to buy it."

"With that new attitude I set about learning to draw, which I never could do before, in spite of the fact that some of my illustrations had been more or less acceptable. I really didn't know the craft of my profession. I think I had imagination then, but really didn't know how to use it. The intervening years when I did movie posters and a few book illustrations were spent in trying to find myself. I used to think that when some other artist did an illustration in a particular way, that proved it was the way to do it. It was only when I began to look at the idea from my own point of view that I started to get any place. It was better if I didn't try to figure out what Parker or Von Schmidt would do and realized that it was my problem, and that from my point of view my experience was just as good as theirs."

"I really don't know myself what makes my own point of view. I do know that it is what people want to buy, whereas they didn't want to buy my idea of how somebody else would do it. One can't achieve any sort of success as an illustrator until one concentrates on and expresses one's own point of view."

A great many young illustrators have stood at the same crossroads that Briggs faced. Most of them have refused or been unable to take the right turn, because they have lacked, first, the downright fortitude that is required for a merciless self-examination and, second, the stamina to slowly and painfully work out their early mistakes.

Excerpted from the October 1950 issue of American Artist magazine, written by Henry C. Pitz

* My Austin Briggs Flickr set.

"I realized that I just wasn't doing acceptable work, because if it had been good, they would have wanted to buy it."

ReplyDeleteLeif, does Briggs' comment remind you of your earlier series on Andy Virgil? The flow of assignments dried up for Virgil as well, and he was convinced that if he flogged himself to work harder and better, he could cure the problem. Sometimes, as in Briggs' case, you are just going through an economic depression. But sometimes, as in Virgil's case, you are just plain on the wrong side of history and there is nothing that human willpower or talent can do to keep you from getting massacred.

In Briggs' case, fiction magazines and advertising assignments would come back and sustain him for the balance of his career. In Virgil's case, the magazines were all dying out for good. The problem is, you never really know until you look back over your shoulder, years later.

While I agree the use of photography cut down the size of market open to illustrators in the 60s and 70s there were still many opportunities for illustrators with the 'right' style for the time.We've just heard from Marvin Friedman, who was able to navigate his way through the period.

ReplyDeleteSome illustrators are just not able to bend their style to the prevailing mood and end up falling by the wayside or taking work far below the status they were used to.

Sad to say, but times change.

David;

ReplyDeleteWhen Anita Virgil and I began corresponding and she told me about Andy's awful fallow period I mentioned that those had been my friend Will Davies' most lucrative years. His "big fish in a small pond" status in Toronto doing very similar work to Andy's made him one of the wealthiest, most sought-after illustrators in Canada during the 60's and early 70's.

Anita replied, "If only we had known there was so much work in Canada we would have moved in a heartbeat."

Charlie Allen did well in SF during those years as well, though the nature of his projects changed dramatically from the kind he had done during the 50's.

Kyle may be right (at least partially so) - adaptability seems to be a key component of success (or at least survival)... but the underlying philosophical truth Briggs discovered, as expressed in today's excert - that you can't succeed until you express your own point of view - is, I believe, the essential of what an illustrator should strive for.

Andy Virgil was just getting his career back when cancer cut short his career (and his life). Who knows how much he might have accomplished?

In any case, working harder and better in an effort to be as good as you possibly can be is a reward in itself, isn't it? Beyond that, I suppose, an indeterminate measure of luck, determination and business savvy...?

this is really inspiring stuff- and the timing's perfect as well.

ReplyDeleteNot that there would ever be a bad time for Briggs -- but please elaborate, tonci -- why is this week perfect timing...? :^)

ReplyDeleteWe (me and tonci) are from eastern Europe (and outside the EU), and for us "now" can mean 'these months' rather than 'this week.'

ReplyDeleteSo, it's a perfect time to address the fate of the illustrator during economic downturn.

Ah, I see... yeah, believe me, I can relate. Thanks, Traven :^)

ReplyDeleteWhat I am understanding here, is that there is no one reason for an illustrator's success or failure in staying busy through changing times. However, perhaps the emphasis on technique is miss-leading in this discussion. During the 60's, 70's, 80's and 90's, there seemed to have been less emphasis on a technique and more emphasis on a whole variety of different techniques, depending on the assignments. In the 40's and 50's there wasn't a lot of different looks, but that all changed in the 60's. Chuck Pyle, a successful illustrator in S.F., kept a realistic Rockwell approach to his illustrations for decades, and found quality work for that look. He is a good draftsman, and I believe that helped sustained him through changing times.

ReplyDeleteI always felt most comfortable doing realistic illustrations depicting real people, and that became the bulk of my illustration work, even through the 90's. I think during financial downturns, an illustrator needs to be willing to find and do their very best at whatever illustration assignments are available to them at the time, not just the ones that turns them on.

Bottom line... myself and the illustrators I knew, looked for the kind of assignments that fit our natural technique, instead of trying to always change techniques to fit what seemed to be selling best. Although, when asked, I could adapt to other technique for a particular illustration request. But, I looked for work that would fit what I thought I could do best.

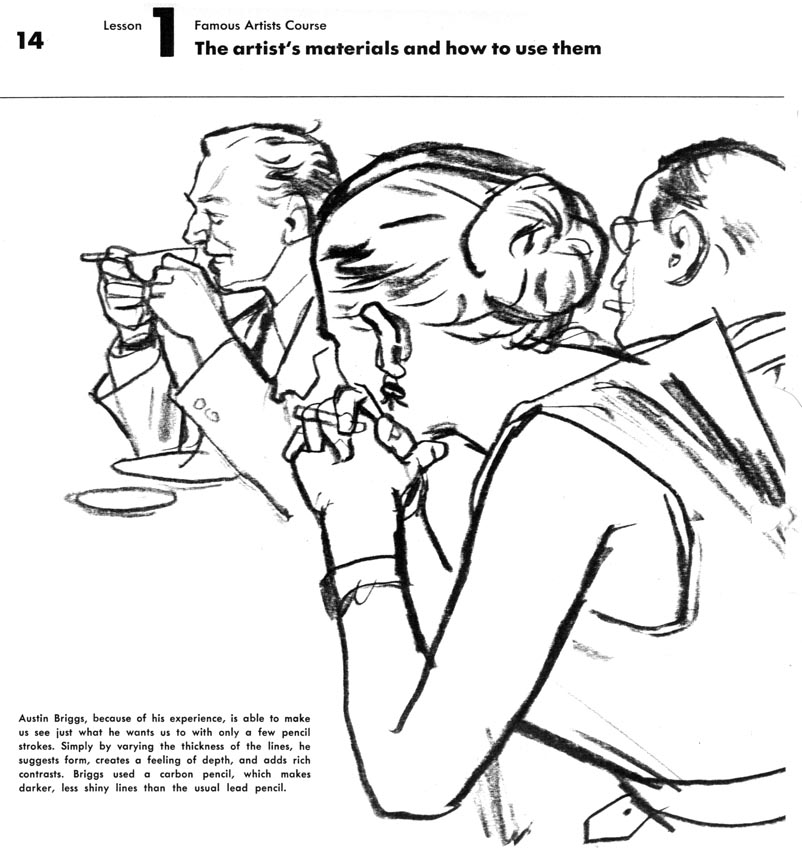

As an illustration student and early in my career, I was influenced by all the top 50's and 60's illustrators, especially Briggs for his line work... but eventually it became obvious that they were doing their technique a hell of a lot better than I could.

I think that is what Briggs meant by finding his own way of doing an illustration.

Tom Watson

Don't mean to hog the show again, but I meant to mention that Leif's analysis is right on the money when he wrote that you have to express your own point of view... but I might add, skilled draftsmanship, as Briggs pointed out, is key to that expression.

ReplyDeleteDraw, draw, draw, and DRAW ALL THE TIME!

OK, I'll shut up now. ;-)

Tom Watson

Hopefully that's what has come across - both in this week's series and in the recent Fawcett week: learn to draw - that's the foundation of illustration, no matter how stylized or computerized your work ends up being.

ReplyDelete* Case in point: read this post by TI list member Von Glitschka

Actually, last week's series on Marvin Friedman was a great example of what you spoke about above, Tom: Marvin found he sometimes had to 'reign it in' but for the most part he was committed to doing it his way.

The point I hope is emphasized to us all is that you must find your own voice to really succeed. I worthy goal we all ought to pursue!

I'm not sure if I'm making myself entirely clear, but further to the above, I mean that today there are a few styles one sees all over the internet. This has long been the problem in illustration: in the 50's perhaps it was Al Parker, in the 60's, Bob Peak and Bernie Fuchs ( into the 70's as well) In the 80's it was Patrick Nagel and in the 90's it was Brad Holland. Now its James Jean. As Briggs said, "I used to think that when some other artist did an illustration in a particular way, that proved it was the way to do it. It was only when I began to look at the idea from my own point of view that I started to get any place."

ReplyDeleteOk, now I'll shut up, too! ;^)

Sterling Hundley has had a recent post about artists' attitudes in difficult times:

ReplyDeletehttp://advice.sterlinghundley.com/2008/11/as-goes-economy-so-goes-career-this.html

Very recommended.

Thanks Traven - that really was a fantastic post. I felt compelled to leave a comment. Thanks for the heads-up. :^)

ReplyDeleteFirst.I love to draw and I'd say I'm pretty good at that.

ReplyDeleteBUT, to be successful in the illustration business these days you do not need to "draw draw draw" every day.You need to read,think,watch TV and films, study fashions, graphics,art and take in the world around you so you can,as Leif and Briggs put it,'find your own voice' and reflect the world around you in your own distinctive manner.Your own viewpoint is the reason you'll get hired- rarely would it be for your accuracy of drawing.They can hire a photographer for that (in their opinion).

So, I'm sorry to differ with Tom on this,I really wish it were as simple as drawing all day constantly honing one's eye.

But it's not.

All the Best.

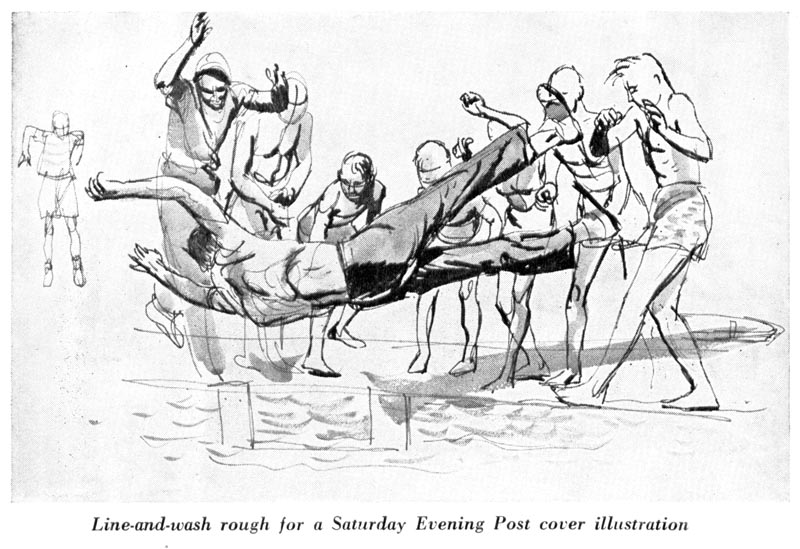

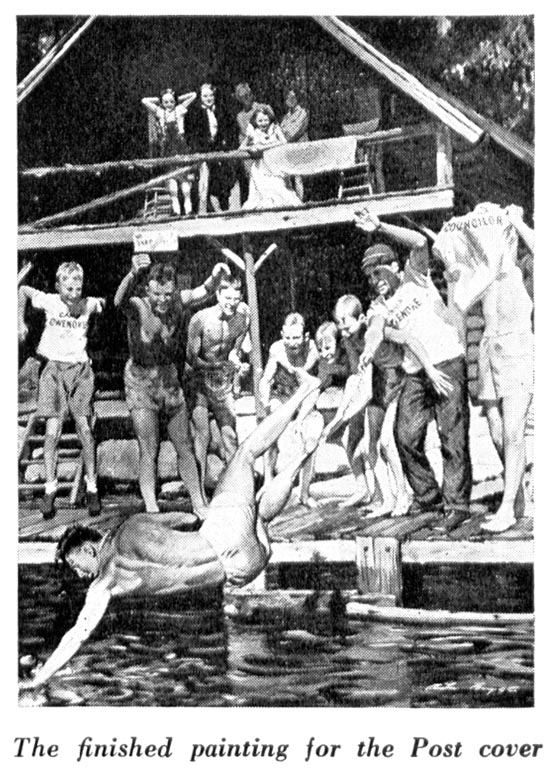

That first picture (SEP cover) looks like a Bruce Weber photo.

ReplyDeleteI think we are actually all talking about the same thing here, but approaching it from different angles.

ReplyDeleteIn the 50's some of what I call the 'Old school' guys who were doing Haddon Sundblom buttery painting styles began losing work to the 'New School' Cooper studio gouache painters. Tom mentioned in earlier comments that in the 60's the ADs were asking for the 'rainstorm' look - that streaky, sketchy technique done with gessoed board and thin washes of colour that Peak and Fuchs championed.

The key there was that throughout those changing times, technique was just being overlaid on solid realistic drawing. If you didn't or weren't able to change your technique you could, as Kyle says, find work - it just might not have been of the calibre you were used to (no major ad or magazine work).

But this is from my perspective where there was a major turning point in illustration: the rise of decorative styles. They were there in the 50's, but they were a sideshow to the main attraction. With the change in popular culture in the 60's, Pushpin Studios and psychedelic posters and underground comics and on and on, suddenly solid realistic drawing wasn't essential to success... I'd even venture to say it could be a hinderance in some markets.

Since then so much has changed - yet everything is, in many ways, exactly the same. Illustration continues to thrive, but in new markets. There are more talented artists pouring into the market than ever before, but many of us are still looking to traditional markets that were waining a half a century ago.

This is a topic I think we'll be grappling with more and more, especially as the current economic situation forces us all to do whatever it takes to put food on the table. :^(

A commendable precis, Leif.

ReplyDeleteOK, I'll give it one more shot. Some have the misconception that good draftsmanship is realistically measured perfectly accurate drawing or paintings like the paintings of Thomas Eakins. A drawing can be simplified, edited, stylized, exaggerated and even distorted, and still be well drawn. But, Its a time tested proven theory that learning to draw accurately gives you the skill and ability to communicate your life experiences with more authority and ability... which is the point I was trying to make before. And, drawing and painting accurately doesn't mean your simply copying what a camera can do. I know that's what some people might think, but unfortunately that's another misconception. I'm not saying life's experiences aren't important, however if an illustrator can't draw well, he's diluting his life's experiences in the mix. A surgeon has to learn the skills of performing surgery first, no matter how much life experience he has. Briggs was very clear when he said he needed to learn to draw better in order to find his own point of view.

ReplyDeleteKyle, I hope you really didn't mean that to be an illustrator today, all you need to do is go out and absorb life and then try to illustrate your point of view the best you can... and learning to draw well is not really important? If that were the case, why not just learn the graphic software programs, go take a long trip and absorb the world, and then go into the illustration business? Sure could save a lot of time and sweat learning how to draw well. Absorbing life kinda happens naturally, if ya have any curiosity and interests beyond the front door. Wouldn't it be nice to absorb the skills of being a superb illustrator as easily as it is to absorb life.

Tom Watson

leif: perfect timing in the sense that i'm actively trying to figure out similar things, so when he says "It was only when I began to look at the idea from my own point of view that I started to get any place" it hits the spot. a lot of the fawcett lines, too (still waiting for the book to arrive =)

ReplyDeleteof course i can't begin to compare myself with briggs, but i think these things trouble everyone who is even remotely serious about drawing.

traven: never thought about economy actually- i still live in the belief that there's always work for someone who can draw (now only need to learn). especially since most of my income comes from storyboards and other marketing things. in any case i would consider myself a failure if i didn't try to do my best at it, regardless of the economy.

some great comments here!

Tom, if you say the words

ReplyDelete"Draw, draw, draw...draw all the time",But what you really mean is practice your craft ie drawing, painting, composition, and design then I wouldnt disagree.

The flavor of your words suggested to me a somewhat narrow approach to being an illustrator in that drawing is the catch all solution to a successful career.

At the end of the day a great idea averagely rendered will take you further than a mediocre idea beautifully rendered.And that is my experience of looking at magazine and book illustration over the last 15 years.

I hope you see what I mean.

most of these guys emphasized the thinking part too- gotta have the technique, and the discipline, but when you have those 'figured out', most of the time you spend as much time thinking as you do pushing the pencil, or more...

ReplyDeleteor did i get it wrong?

Nope - you definitely got it right, tonci :^)

ReplyDeleteTonci; Further to your comment earlie, I'm so glad to read that - its exactly how I felt upon first reading this article I've excerpted ( and also the earlier Fawcett 'On Drawing' excerpt) - as though they were speaking directly to me.

ReplyDeleteFrankly, I felt a little ashamed, as though confronted by a reality I was hoping to ignore. I've been at it for twenty years and in the back of my mind I'm always thinking, "you know, you could push yourself to improve... take that evening life drawing course... do some sketching instead of vegging out in front of the tv..."

Ultimately, who knows if these articles will be the catalyst that moves me, you or anyone else who has read them to do what we know we ought to do... but presenting them and giving them consideration is at least a step in the right direction.

I very much appreciate you speaking up - its comforting to know I'm not alone in feeling this way about my own work :^)

i consider myself extremely lucky, having found this blog at this point in my life- could've been ten more years before i even heard about guys like briggs, and ten more before i'd find as many pictures. these articles and scans are priceless. when sickles was young he learned in a library- one can certainly find the same thing here. you get to see what can be done and learn about people who did it (and how) and also you often get a swift kick in the butt- so you can get off it and go and try to attain 1/18th of the skill these guys had...

ReplyDeletebut yeah, thanks! ;)

Kyle, I think generally speaking, we are probably on the same page. I view drawing, design, composition, etc., as part of the process of rendering... not separate functions. 50 years ago, my first illustration teacher told us that if we learned to draw well, we would always find work in illustration... and I don't think that has changed. For 40 years, I could always find assignments that needed my ability to draw. And, I have also seen good ideas get shot down because they were poorly or unconvincingly rendered.

ReplyDeleteIt has been my experience that personal point of view and life experiences will be different for every illustrator, as it was for Briggs. Briggs was still a relatively young guy, and probably still impressionable when he questioned his ability as an illustrator. Your comment about a great idea averagely rendered is more important than a mediocre idea beautifully rendered may be correct today, but what little illustration I see in today's advertising, TV and magazines, are neither beautifully rendered nor "great" ideas. Also, there was a time when even an "averagely" rendered illustration was not a bad rendering, and great ideas came from those that could also render beautifully... like Briggs or Al Parker. So I don't think we can really separate the two, at least not during the mid century.

Tom Watson