That day became a turning point in Murray Tinkelman's career. In an interview with TI list member Neil Shapiro published in Illustration Magazine #18, Murray described what happened next:

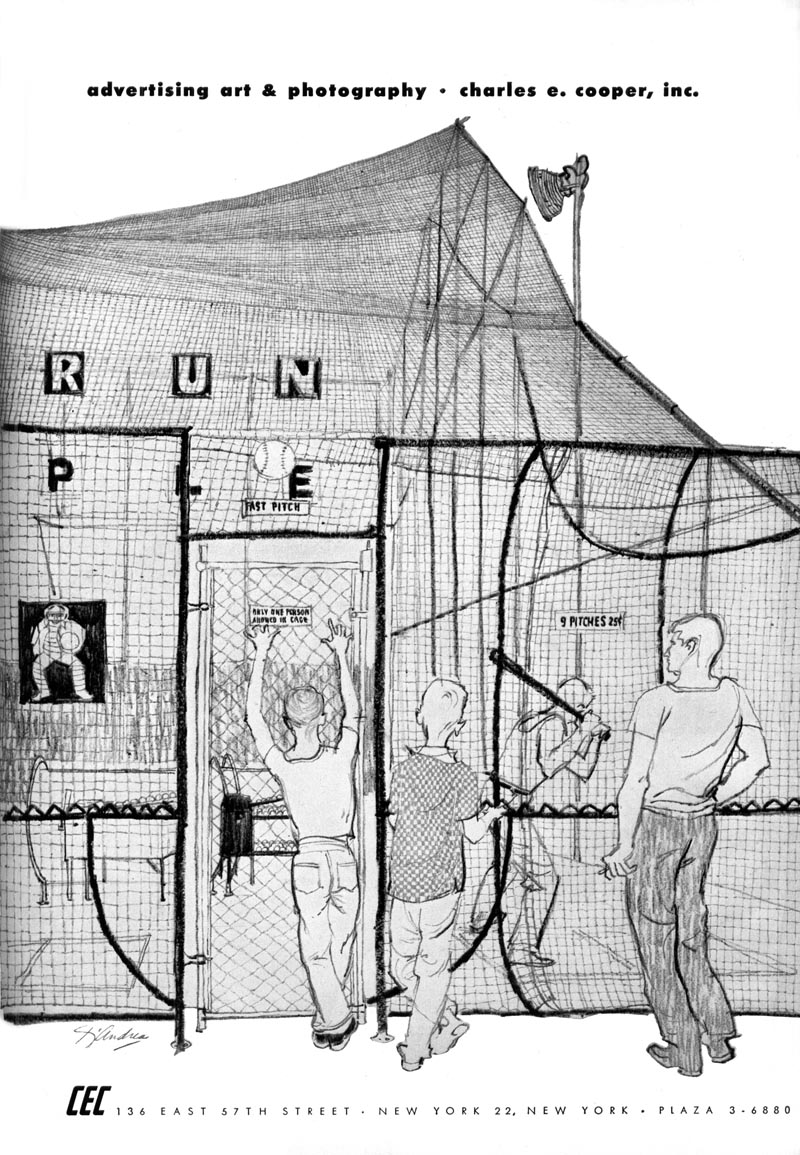

"I was looking through [the 1956 Art Directors Annual]. I came across a stopper -- an absolutely beautiful pencil drawing of some people leaning up against a wire mesh fence looking in at a baseball batting situation. It was a marvelous drawing - beautifully composed, beautifully drawn with a modern flair to it."

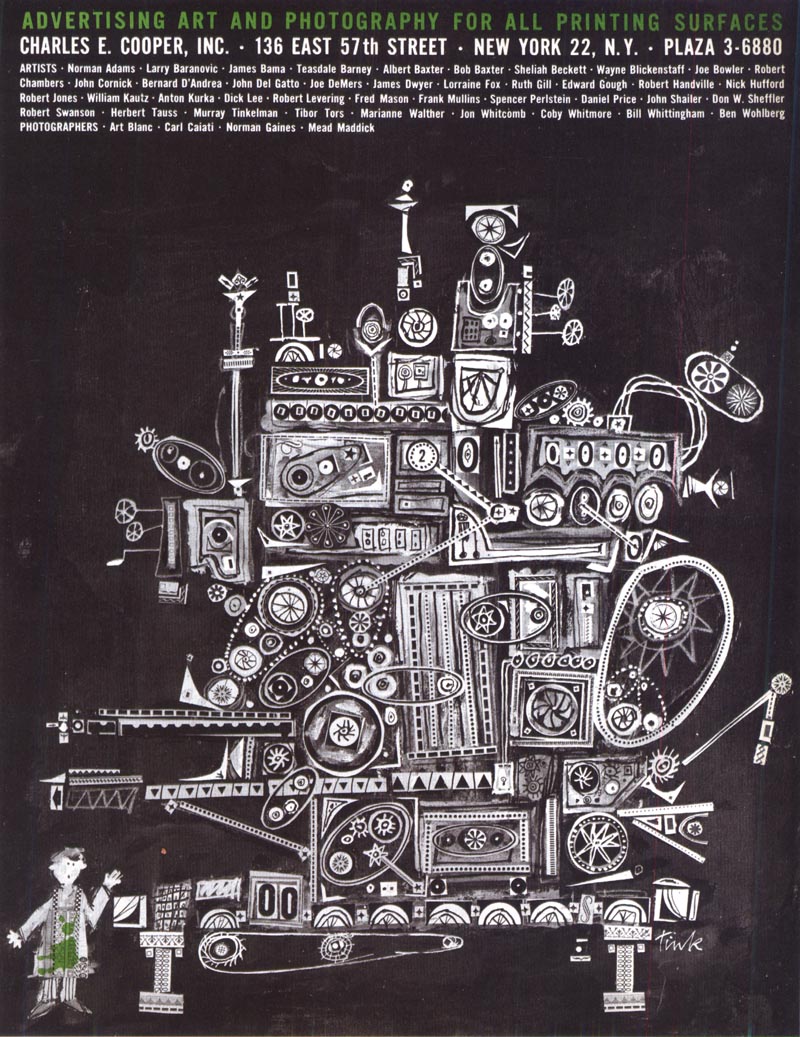

"I noticed that it was an advertisment for the Charles E. Cooper Studios. I'd never heard of Cooper Studios. I did not know the name Bernie D'Andrea, which was the name on the drawing that attracted my attention. So I called Charles E. Cooper studios to make an appointment to show some samples."

It was an interview that almost didn't happen. That Thursday in the reception area at Cooper Studios while waiting for his turn to be meet with Chuck Cooper, Murray got cold feet. "But," he says, "I couldn't get out of there fast enough and they called my name before the elevator came."

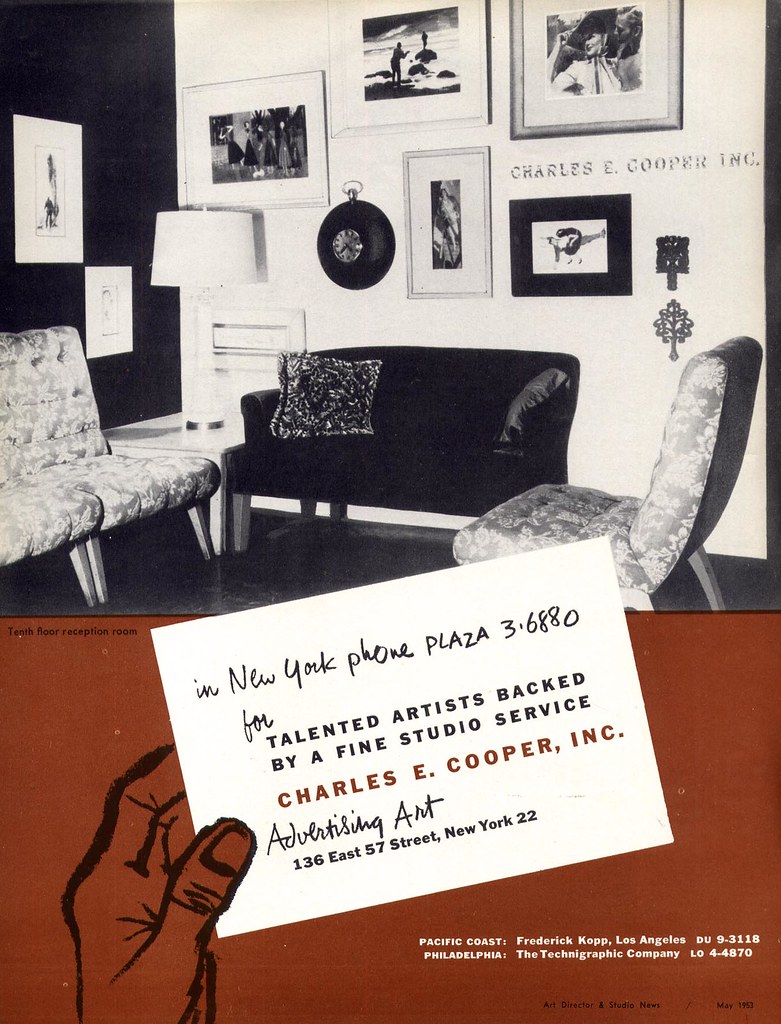

"Chuck had this gorgeous corner office on the ninth floor in this building on the corner of Lexington and 57th St with windows on two sides... it was just this gorgeous, light-filled office with indirect lighting and copper-leaf walls. And he looked through this terrible portfolio I had brought."

Based on what he had seen while fretting in the reception area, Murray's interview with Cooper was not what he had been expecting.

The artists who had interviewed before him seem to have been in and out again in about thirty seconds each. By comparison, Chuck Cooper devoted an inordinate amount of time to Murray's portfolio. He carefully examined each piece, then turned it over and stacked it carefully in a pile. Then he turned over the pile and examined each piece again. When he was at last finished Cooper looked up at Murray and said, "All right, be here Monday."

Murray says, "I accepted the position at Cooper, and I had no idea I was now completely freelance - and with no income."

"The next day I showed up at Wallace Brown and I said to the art director that I was going to have to leave. Immediately. Because I had been hired by Cooper Studio. And he was so relieved because he liked me. He had heard of Cooper and he had nothing but admiration for it so he said, "Terrific - good for you - go with God!" He didn't try to keep me at all because I was awful!"

"So I went home and I said to Carol, "I quit my job." Here she's pregnant, we had no money in the bank... she said, "You what?!"

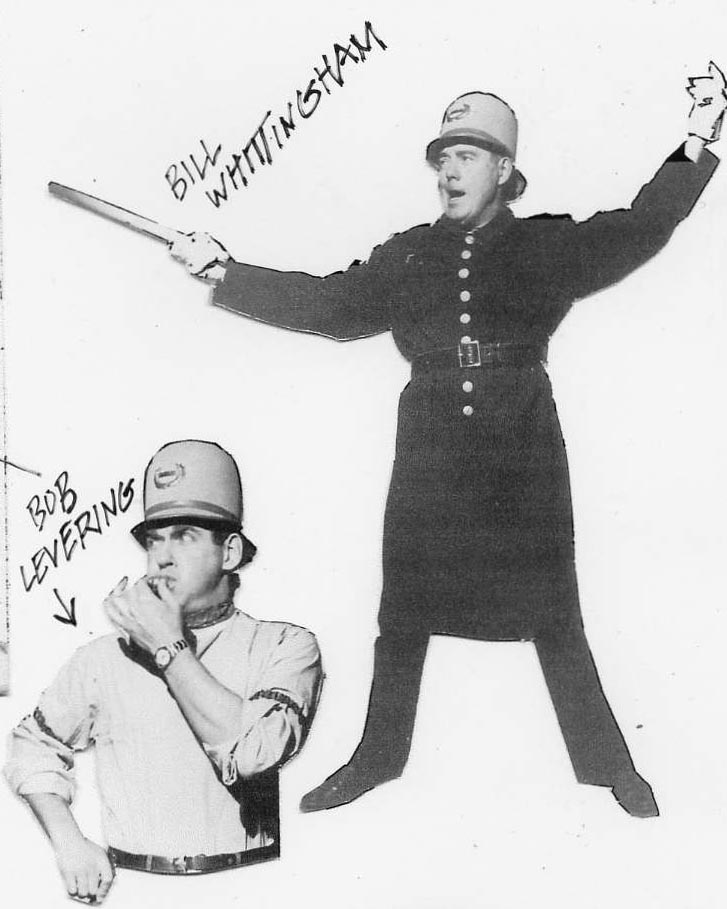

"So Monday morning I show up at Cooper Studio. There were two full floors, the 9th and the 10th floor. They had one suite of offices on the 11th floor that had broken Lucies and busted furniture... a couple of old Steven Dohanas tabourets... it was a shambles. And that's where they put me. And I shared that space with Bill Whittingham, who's now a portrait painter (he was Joe Bowler's heir apparent) and Nick Hufford, who was originally an apprentice to Haddon Sundblom..."

"...and a thorough alcoholic and maybe the funniest man I ever met in my life - Nick was insanely funny."

"So we'd go down to the bullpen to get art supplies, and I'd get introduced around by Bill Whittingham. The first person he introduced me to was Bob Levering (who was and is the sweetest man in the world). Levering became instantly supportive of me."

That first year as a Cooper freelancer was incredibly demoralizing for Murray. He told me about his first job for the studio:

"There were about five salesmen at Cooper", he explains, "and one of them brings back this job. I took a shot at it and he couldn't understand it and he didn't even like it. He gave it to another artist, Bob Swanson, to redo. Bob did a pretty competent job," he chuckles. "It went through, but they never even showed mine."

"Finally after maybe two months of this, I went into Chuck's office and told him, "Hey, I gotta leave. I'm starving to death here. Bills are piling up... we're about to have a baby..."

"And Chuck said, "How much do you need -- to live?" So I said, "Well, at least ninety dollars a week (which was ridiculous... it was just a figure that jumped into my head, it was way too low)." So he said, "All right, I'll put you on a ninety dollar a week 'draw'. A 'draw' was a payment against income I was supposed to generate for the studio.... except I didn't generate any income! So I'm going deeper and deeper in the hole... and Chuck never, ever said, "Where's the money... when are you gonna pay me" ... nothing like that. At all. There's gotta be a heaven ... for Chuck."

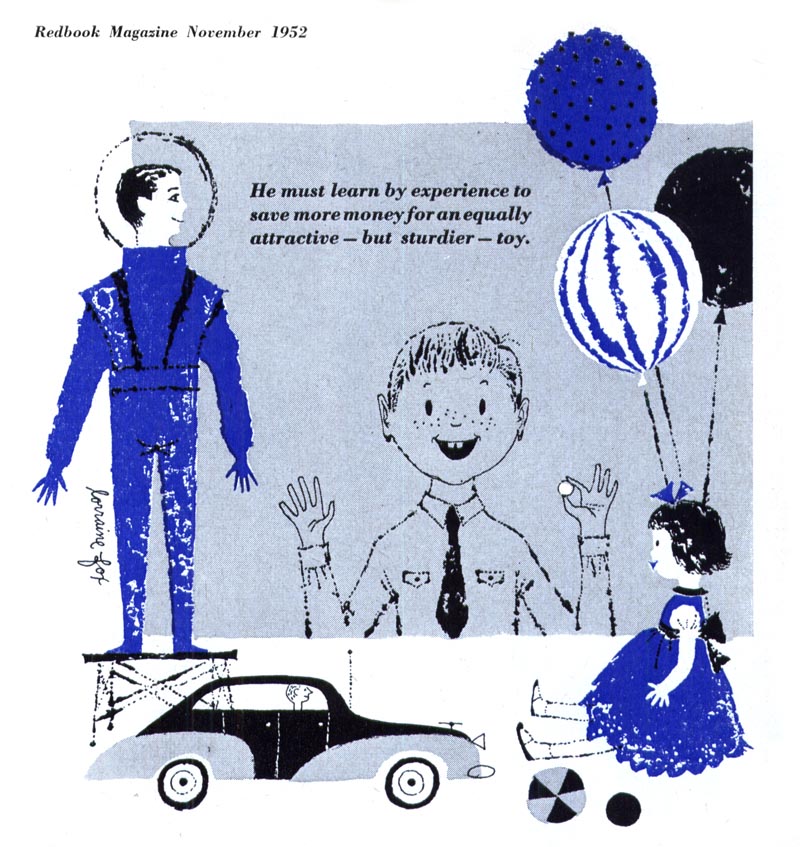

Murray has often spoken about his great affection for Lorraine Fox and his admiration for her work. He has gone so far as to say "Lorraine Fox was my hero". But when he first met her during his early days at Cooper he was surprised to discover that they were not exactly on the same page:

"Lorraine was a very quiet, very reserved lady. And underline lady. She was a Lady. Very elegant, a very handsome woman... "

"...and I was... disappointed by her lack of response to what I was doing. I was in the bullpen getting something matted. And Lorraine came in and she was getting something matted before she delivered it. She didn't say my work was crap or anything, but she just looked a little cool about it."

"And I mentioned it to one of the other illustrators, Don Crowley, and he said, "Don't worry about it. Lorraine has her own goody factory and maybe she just doesn't understand."

"What I was doing at that time was pretty rough. It had touches of abstract expressionism... 'gallery painting'... pretty sloppy stuff."

"I was kind of disappointed that Lorraine wasn't more responsive to what I did (and neither was her husband, Bernie D'Andrea - he looked at me like I had two heads). But Bob Levering, and through Levering, Joe Bowler and Coby Whitmore and Joe DeMers became my support system."

I asked Murray to decribe his first really big, well-paying job at Cooper's:

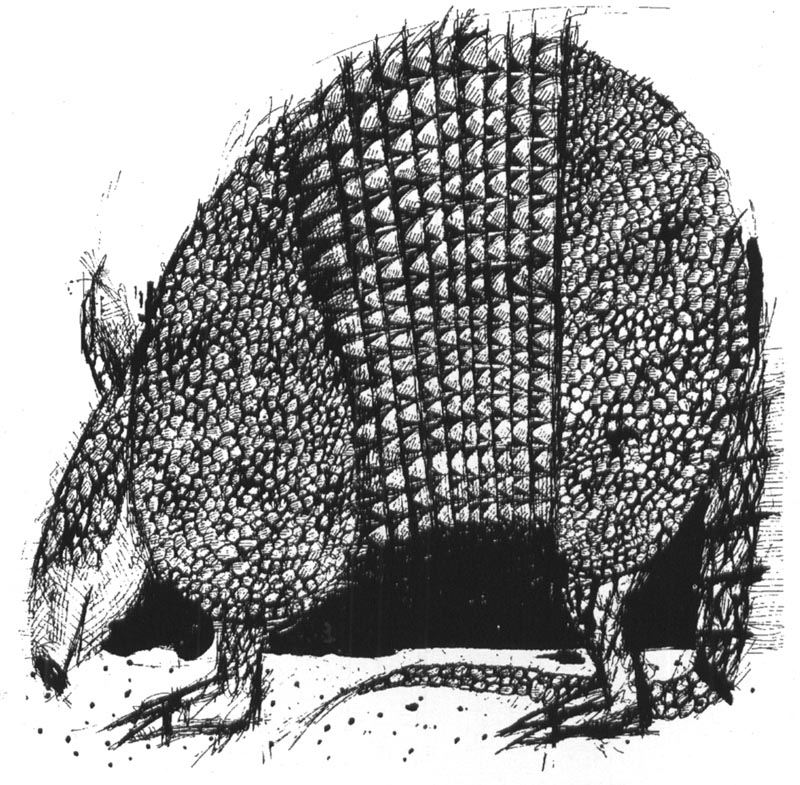

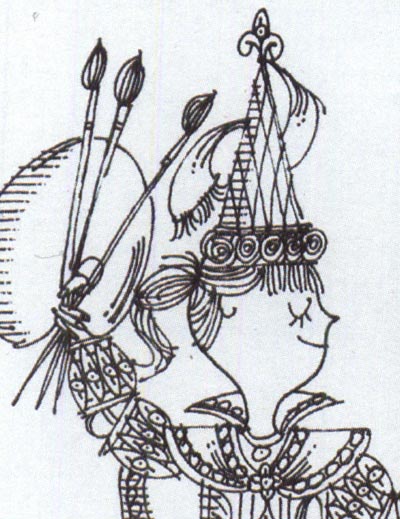

"One of the salesmen came in with a job from the Grollier's Society. They were publishing an encyclopedia for high school kids. And I got $1,800 for that one job, which was as much as I had made the entire previous year. They were these very ragged drawings... kind of an expressionistic pen-and-ink style."

"It was great! I got cocky immediately... maybe on the edge of insufferable. I mean, here I am, a big-shot now, and starting to make some money for Cooper."

"That was a break-through. I don't think I was ever in the red again after that job... there was always something on the board, there was always a cheque in the mail."

"Fast forward for a minute here: there was a point in 1961, when I did my first Saturday Evening Post job. And it was a thousand dollars for one painting. And I went into Chuck's office and I gave him a cheque for five hundred dollars. Now Chuck did not take any money from editorial jobs -- he only took money from advertising -- and this was an editorial job. He said, "What are you doing?" and I said, "Well, you staked me to that draw." And he said, "Well can you afford this?" And I remember saying ,"I can't afford not to do this." So he took the cheque - reluctantly."

Murray chuckles, "He said I'm the only person in the history of the Cooper Studio who paid back money from a draw."

* My Murray Tinkelman Flickr set.

Amazing post, Leif! Murray's work is really interesting, and the background/interview only adds to the draw - thanks for sharing this with us!

ReplyDeleteThanks for the memories - I recall Chuck Cooper as amazing, generous man and the story confirms it.

ReplyDeleteAs a student and friend of Murray his life is a artistic ride of pure motivation. Tinkelman has influenced so many illustrators. He will go down in history as the "Babe Ruth" of illustration... A pure giant in the industry.

ReplyDeleteActually... it was Robert Fawcett ...the "Illustrator's Illustrator" who gave that title "Babe Ruth of Illustration and/or "Cooper's Babe Ruth" to "Norman Adams"................it also would be nice if you were to acknowledge the Sites you quote your wisdom from.

DeleteThankx