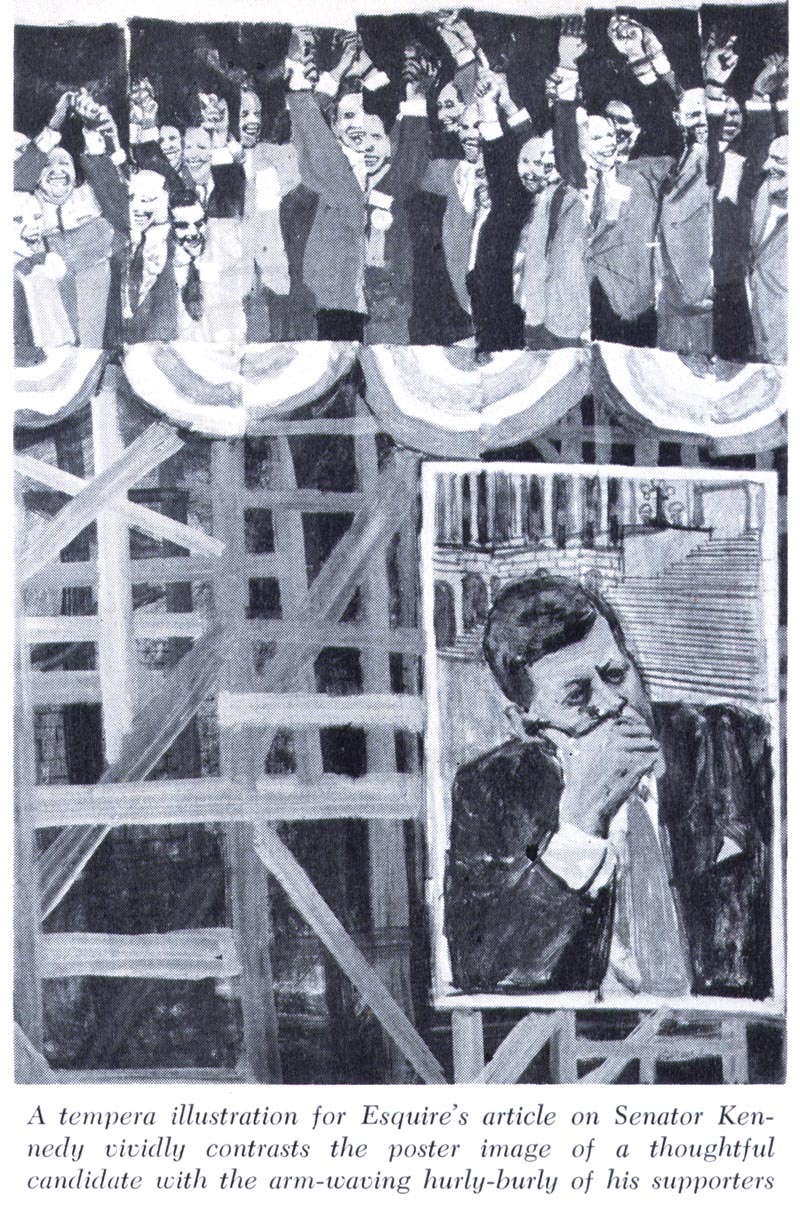

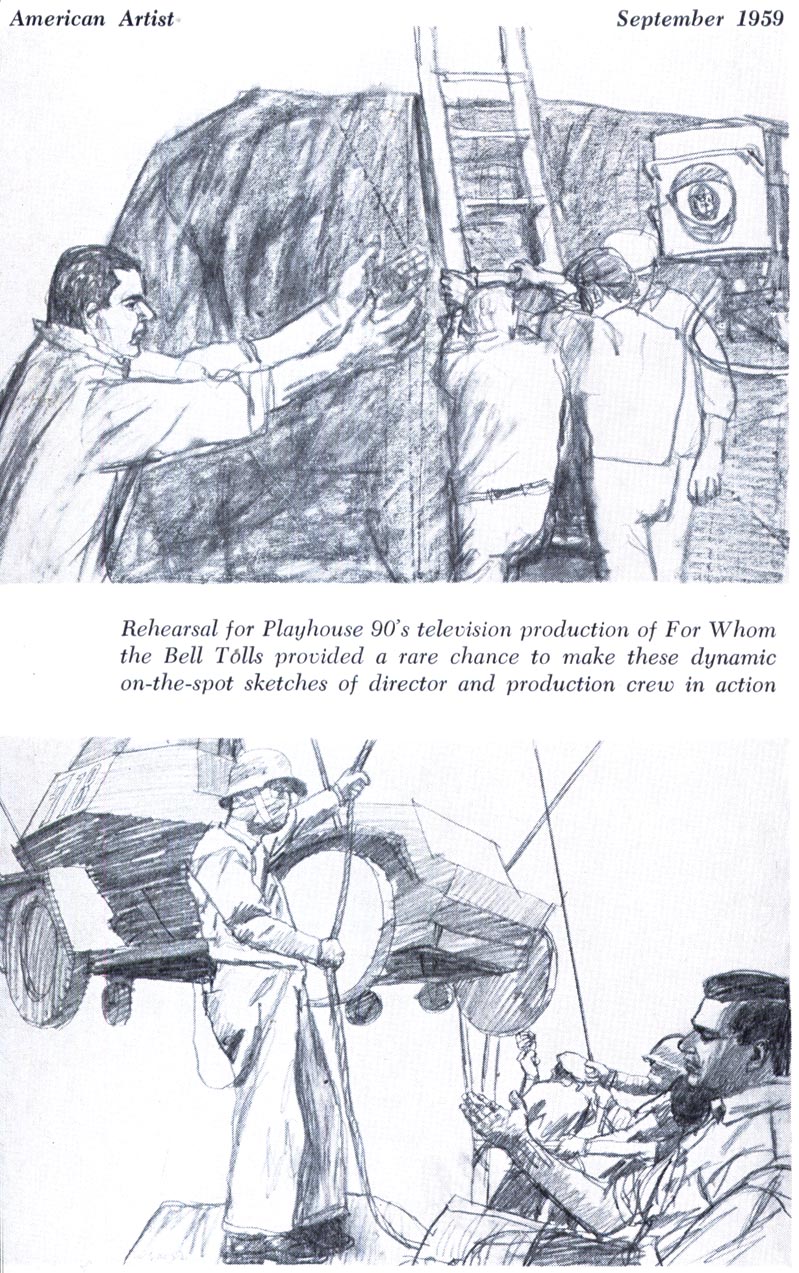

All of which makes me think this would be a wasted opportunity if I did not use it to present what some might call "the Anti-Wyeth": Robert Weaver. Because for all of the tradition and craft in Wyeth's work, for all of the gorgeous, thoughtful, classical composition, for all the "timelessness", there was, by the 1950s, hardly a trace in the mainstream print media of NC Wyeth or any other artist who might be considered to have followed in his footsteps. There was, however, a burgeoning movement of young, avant-garde, modern art-influenced illustrators who seemed to be laughing in the face of all the traditions their elders considered prerequisite to good, proper picture-making.

Some would say Robert Weaver was the leader of this gang of young punks. At the very least he must be considered one of it's chief agitators.

In a 1959 interview in American Artist magazine, Weaver said, "...rather than emphasize the difference between the painter and the illustrator I would like to show how 'art' and illustration could serve each other."

This is an incredibly important statement and marks a defining moment in the evolution of illustration as it exists to this very day. Before Weaver, most illustrators saw themselves as purely commercial artists - craftspeople - whose highly skilled efforts were essentially in service of the story or advertisement that required visual reinforcement.

After Weaver, illustrators began seeing themselves as a sort of hybrid commercial/fine artist; someone who must have the freedom to include some degree of sincere personal artistic statement in their assignments. The story was now in service to their requirement for personal expression.

To put it plainly (and I have seen this most often among editorial illustrators) those artists who follow the Weaver philosophy want to have their cake and eat it, too.

From past experience, I know some readers are going to remain firmly entrenched in the Wyeth camp and everything it represents. They will see Robert Weaver's work as unskilled and unworthy of serious consideration or respect. Other readers, I know, adore Weaver and see Wyeth and other traditionalists as hokey and "compromised." Amusing but also somewhat contemptible. I ask both parties to keep an open mind and see where this week takes us (but of course, all comments and opinions are welcome and I look forward to hearing whatever you care to contribute to the discussion).

* My Robert Weaver Flickr set.

Well, faces -- we each bring to the representation of faces an expert opinion, do we not? However diffidently we talk about true and false to, say, our kids,Warner's drawings make for a pretty easy decision, however beautiful we find Wyeth's paintings.

ReplyDeleteHave always liked Weaver---good to see you focus on him this week Leif. Nick Meglin (right, of Mad mag...) gave him a chapter in a book he did back in '69 called 'On The Spot Drawing' (Watson-Guptill Pub). Worth looking for if you don't already own.....

ReplyDeleteI'm dense, but fail to see the supposed controversy. Never thought of NC Wyeth as anything but a great early illustrator. Robert Weaver I respect. But hey....all the great mid century illustrators (Parker, Fawcett, Ludekins, et al) aren't exactly chopped liver. Their work and opinions matter every bit as much as Wyeth, Weaver, or any other illustrative viewpoint.

ReplyDelete"Before Weaver, most illustrators saw themselves as purely commercial artists - craftspeople - whose highly skilled efforts were essentially in service of the story or advertisement that required visual reinforcement."

ReplyDeleteThis is not entirely accurate. Howard Pyle, Wyeth's teacher, emphasized the ability of illustration to produce masterpieces of painting, and encouraged his students to think accordingly. Certainly Rockwell was always aware of the importance of his originals, despite all the assaults of the Moderns against him.

I'm a Wyeth fan but also admire a lot of Weaver's work. It should be noted that Weaver's process and ingenuity was in part a response to a physical challenge that might have defeated lesser artists. As a result of several cataract surgeries and glaucoma, he had serious vision problems. When working he wore a giant headgear with microscopic lenses.

ReplyDeleteI also appreciate both N.C. Wyeth and Weaver, for different reasons. But, one common denominator was that they were both excellent illustrators, regardless of ones preferences. Although Weaver's drawing wasn't as academic as Wyeth, it was usually effective for the times and well done.. certainly consistent with his contemporary avant-garde approach. I don't think Weaver looked at the early illustrators like Wyeth as insignificant and no longer important. Weaver never abandoned traditional representational figures, although he did stylize them at times. Weaver often used abstraction to break up his compositions into flat expressionistic fragmented pieces, and Wyeth used abstraction in his literal compositional design structures.. abstract in shapes and paint texture with impressionistic brush strokes. Most illustrators from the Howard Pyle school painted in a similar manor as many fine artists of their day. And, Robert Weaver was one of the first illustrators that rendered like the new wave fine artists of his day. I think they actually had more in common than we might expect.

ReplyDeleteTom Watson

Zach; thanks for that info about meglin's book - I'll make a note to keep an eye out for it!

ReplyDeleteCharlie; I hope this week's presentation is not going to be seen as a "controversy" - more as an interesting "compare and contrast" - a look at an evolutionary development in the history of the illustration business - but no doubt some readers who are typically so inclined will default to the controversy position. I'm hoping most will be patient while I develop the theme.

Steven K; I did qualify that statement with most ... I don't doubt there were exceptions. I'm working with a broad brush to make a point - but thanks for that additional info regarding Pyle and Wyeth. :^)

Constance; that's very interesting about Weaver's physical challenges! I had no idea - thank you for that insight.

Tom; As usual you are beating me to the punch - and knowledgeable perspective on the subject is certainly welcome. After all, it was you who first introduced me to Robert Weaver's work, so this week is intended as a follow up to what you initiated last time we looked at this artist. Thanks. :^)

ReplyDeleteIt's a very interesting theory.

ReplyDeleteI can't help but think of Manet and his impact on the Salon painters, who accused him of deliberately painting crude, ugly pictures that looked like cut-outs and made very little apparent effort to create spatial illusion.

I also remember back in art school (30+ years ago) being under pressure to create work that was "sophisticated" rather than beautiful -- and remember J.S. Sargent being openly derided as a sentimental hack at least by one instructor . When I was young, this was an easy attitude to accept, I think partly because the "modern" styles seemed far more achievable than the traditional ones (which I then lacked the skills to do!). Now that I'm older I'm much more skeptical and self-critical. And I'm entertaining the idea that Manet's critics weren't altogether off-base; most of his pictures do seem ugly to me now, and charmless.

Here's a slideshow of some more of Weavers stuff from the NY Times, 1962.

ReplyDeletehttp://www.nytimes.com/slideshow/2008/02/24/opinion/20080224_WEAVER_SLIDESHOW_2.html

Along with the others, I don't see the dichotomy. Weaver lived in a different era that presented him with different challenges from anything that Wyeth knew. For example, if I don't dress and act like my great-grandfather, it's because I'm not him, and it's not 1920 anymore. Same goes for Weaver's art. I don't even see a huge difference in drawing style, really. Howard Pyle and his generation were very much influenced by the English and German illustration coming out in the 1860's. Wyeth's art, for however classic it was, is very impressionistic. In its own way, in its own day, it was a quite modern approach - an approach that must have looked absolutely slapdash to anyone looking at the original canvases.

ReplyDeletePersonally, once I saw Weavers work, all that came before me and everything outside of my education as an illustrator that spoke to me as an artist back in the day - finally clicked.

ReplyDeleteWish I could have found more of his work back then and now. Many thanks for the collection and posting.

cheers!

Nathan, love your stuff, by the way. Without trying to pry, I'd really like to hear how Weaver's work made everything else 'click' for you. How did Weaver's approach make the other things make sense?

ReplyDeleteQuite an interesting subject once again here:

ReplyDeleteHow modern can an illustrator become? How far can he go?

Perhaps I have a story as about as far as he or she illustrator can't or won't go....

The late Joseph Beuys had a show of his works at a German art museum. The exposition featured one of the modernists famous "grease" objects; like heavy blocks of fat on a chair, for instance, which were something like the artist's trade mark. In the case of this particular museum it was a bath tub displayed, lubricated with a thick layer of grease.

This was considered rather dirty by the cleaning woman tasked to clean up the museum halls after close-down. She diligently cleaned the bathtub as well.

Next day the exhibitors found themselves tearing their hair: a catastrophic event had taken place! A priceless object of art had been destroyed!

It became an insurance case, with the insurer's tough job to calculate an exact estimate of the eventual loss incurred!

Probably the cleaning-woman would have prefered an illustration ad from Today's Inspiration to the Beuys grease-bath-tub-art-work. Nothing against Weaver, but me probably too -;)

For the record - Weaver's eye problems didn't affect him until after the 1960s. His style in the 1950s was a conscious attempt to get more of his own personality - his stamp - into the painting, not a symptom of bad eyes.

ReplyDeletesome great slideshows of weavers works can be found here:

ReplyDeletehttp://meltonpriorinstitut.org/pages/pictorials.php5

Greetings, David