But despite his best efforts, no government official in any department was interested. After many rejections Rockwell found himself making once last appeal; to the Office of War Information "or, to speak plainly," wrote Rockwell in his autobiography, "the propaganda department."

"I showed the Four Freedoms to the man in charge of posters but he wasn't even interested. "The last war you illustrators did the posters," he said. "This war we're going to use fine arts men, real artists."

Finally, almost coincidentally, Rockwell showed the Four Freedoms to Saturday Evening Post editor Ben Hibbs, who immediately, enthusiastically commissioned their completion. "Drop everything else," said Hibbs, "just do the Four Freedoms. Don't bother with Post covers or illustrations."

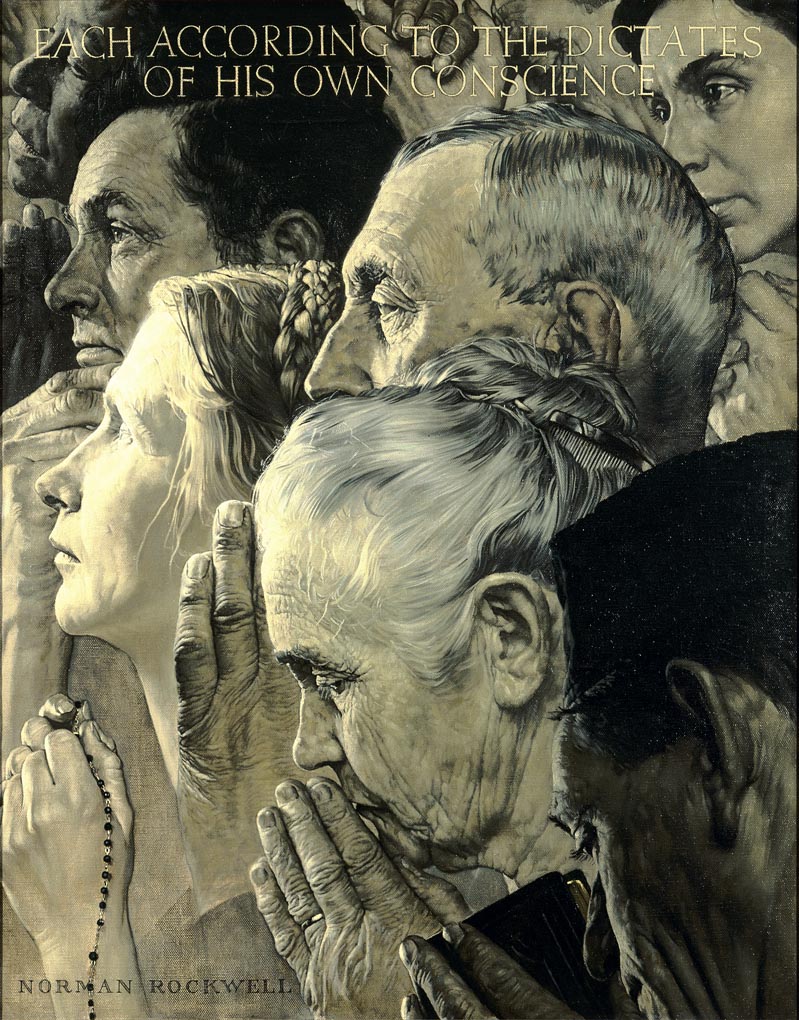

Rockwell spent six months on the four paintings. 'Freedom from Want' and 'Freedom from Fear' (both above) came quite easily... but he struggled tremendously with 'Freedom of Speech' and 'Freedom of Worship' (below), wanting to make his feelings on these subjects abundantly clearly to all those who would eventually see them. Rockwell painted and repainted these two pieces until he was satisfied he had "boiled it down into a clear, precise statement."

When the Four Freedoms were done, "The results astonished us all." Wrote Saturday Evening Post editor Ben Hibbs. "Requests to reprint came in from other publications. Various Government agencies and private organizations made millions of reprints and distributed them all over the world."

"The Treasury Department took the originals on a tour of the nation... to sell war bonds. They were viewed by 1,222,000 people in 16 leading cities and were instrumental in selling $132,992,539 worth of bonds."

"'Freedom of Worship' and 'Freedom of Speech' hang in my own office, and I love them. They are a source of daily inspiration to me - in the same way that the clock tower of Old Independence hall, which I can see from my office window, inspires me. If this is Fourth of July talk, so be it. Maybe this country needs a bit of Fourth of July the year round."

Hibbs continued, "Visitors... always exclaim over these paintings. They marvel at the depth of feeling which Norman was able to build into those pictures. Many people have asked me whether I regard the 'Freedom of Worship' and the 'Freedom of Speech' as great art. I do. Norman himself probably would disagree.

"He has always modelled himself an 'illustrator' with no pretensions of fine art."

* The Four Freedoms, as reproduced in today's post, appear courtesy of the Norman Rockwell Museum

Freedom from Want, Norman Rockwell. 1943. Oil on canvas, 45 ¾ x 35 ½" Story illustration for The Saturday Evening Post, March 6, 1943 ©1943 SEPS: Licensed by Curtis Publishing, Indianapolis, IN From the permanent collection of Norman Rockwell Museum

Freedom from Fear, Norman Rockwell. 1943. Oil on canvas Story illustration for The Saturday Evening Post, March 13, 1943 From the permanent collection of Norman Rockwell Museum ©1943 SEPS: Licensed by Curtis Publishing, Indianapolis, IN (S569)

Freedom of Speech, Norman Rockwell. 1943. Oil on canvas, 45 ¾” x 35 ½” From the permanent collection of Norman Rockwell Museum ©1943 SEPS: Licensed by Curtis Publishing, Indianapolis, IN Story illustration for The Saturday Evening Post, February 20, 1943

Freedom of Worship, Norman Rockwell. 1943. Oil on canvas, 46” x 35 ½” Story illustration for The Saturday Evening Post, February 27, 1943 ©1943 SEPS: Licensed by Curtis Publishing, Indianapolis, IN From the permanent collection of Norman Rockwell Museum

These 4 pieces are so stunning and so meaningful. They are an American treasure!

ReplyDeleteNo matter how many times I see these great illustrations, they never fail to take my breath away.

ReplyDeleteDitto to the remarks above. In 1953, when I was 13, I sent Norman Rockwell a letter telling him how much I liked his illustrations and that I wanted to be an illustrator someday. He wrote back a cordial letter thanking me and wishing me luck in my endeavor. A few days later came a large cardboard tube in the mail, and rolled up inside of the tube were a set of reproductions of the Four Freedom paintings. Freedom of Speech was signed in ink, "My best to Tom Watson, Sincerely Norman Rockwell." It is framed and now hangs in our guest bedroom. Needless to say, they are one of my most prized possessions to this day.

ReplyDeleteHappy 4th of July, and thanks for the appropriate post, Leif.

Tom Watson

These are classic examples of propaganda done correctly and successfully. The fact that so many people forget that it is propaganda and instead look upon these great pieces of art as symbols of their personal and national identity is a testament to the genius of the artist and the way he conveys the message.

ReplyDeleteThanks for posting these! They never get old!

Looking at "Freedom From Fear" at the Rockwell Museum a couple of years back brought tears to my eyes. A extremely powerful piece, as effective today as when it was first painted, I think.

ReplyDeleteThe independent animator,

ReplyDeleteI agree with your assessment of Rockwell's Four Freedoms paintings. However, just the word "propaganda" can be misleading (a knee-jerk negative connotation) for some people.

definition:

"prop·a·gan·da

[prop-uh-gan-duh] Show IPA

–noun

1.

information, ideas, or rumors deliberately spread widely to help or harm a person, group, movement, institution, nation, etc.

2.

the deliberate spreading of such information, rumors, etc.

3.

the particular doctrines or principles propagated by an organization or movement."

Unfortunately it's the negative view of "propaganda" that draws all the attention. I think that Rockwell did mean the Four Freedoms paintings to be "symbols of America's personal and national identity". This was what they risked loosing if they didn't continue to come together as a nation and fight for victory against Nazi Germany and Imperial Japan. Those paintings are such monumental reminders of our history during that time, that I hate to attach a label to them like "propaganda," even though the government used them as a propaganda tool to inspire and raise money for the war, through war bonds sales. For most Americans, they were far more than that, as suggested by your's and other comments.

Tom Watson

I've been to Thanksgiving dinners that "felt" like the one portrayed. I've been tucked in like those children. I've seen all sorts of different religions practicing without disturbance in New York where I live. And I've been at town meetings where people complain and heard the worst slanders spoken against president after president without retribution.

ReplyDeleteThese are masterpieces of truth.

The Norman Rockwell Derangement Syndrome that plays so often online and in pseudo-sophisticated culture circles is boring, provincial and the product of unhappy minds that can only think in terms of criticism and negativity.

Tom and Kev,

ReplyDeleteAs someone who considers much of his work to be in the realm of propaganda (whether overtly so or not), I do not consider this to be a dirty word. I am proud to work in propaganda, because it is a powerful tool that can be used correctly for the good of humans everywhere.

Anytime you need to mobilize a group of people to work toward a common purpose, whether as a country, company, or even a family, you will find that you have to overcome the divisions between people before you will accomplish anything. That is why pictures like Rockwell's were so important: they emphasized the "us" rather than "us but not them."

This was a big problem for the U.S. government. As my grandfather said of his entry into the Navy in 1943, "The recruiter told me how we would fight side by side, but that first night in boot camp we fought the Civil War all over again."

Yes, these Rockwell pictures ARE propaganda. That doesn't mean that they are not grounded in some truth or that they are cynical attempts to manipulate people for selfish purposes. Yet you cannot deny that Rockwell painted idealized images intended to tug at the heartstrings in order to persuade people to say, "Yes, that is the way I want to live, and I will fight to protect it."

Personally, I find it odd that propaganda machines are today used globally to unprecedented levels, yet people still consider it to be a dirty word. It kind of reminds me of the quote, "The biggest lie the devil ever made was that he didn't exist."

It is my hope that we embrace propaganda, both the word and the industry, and use it correctly to its full and positive effect.