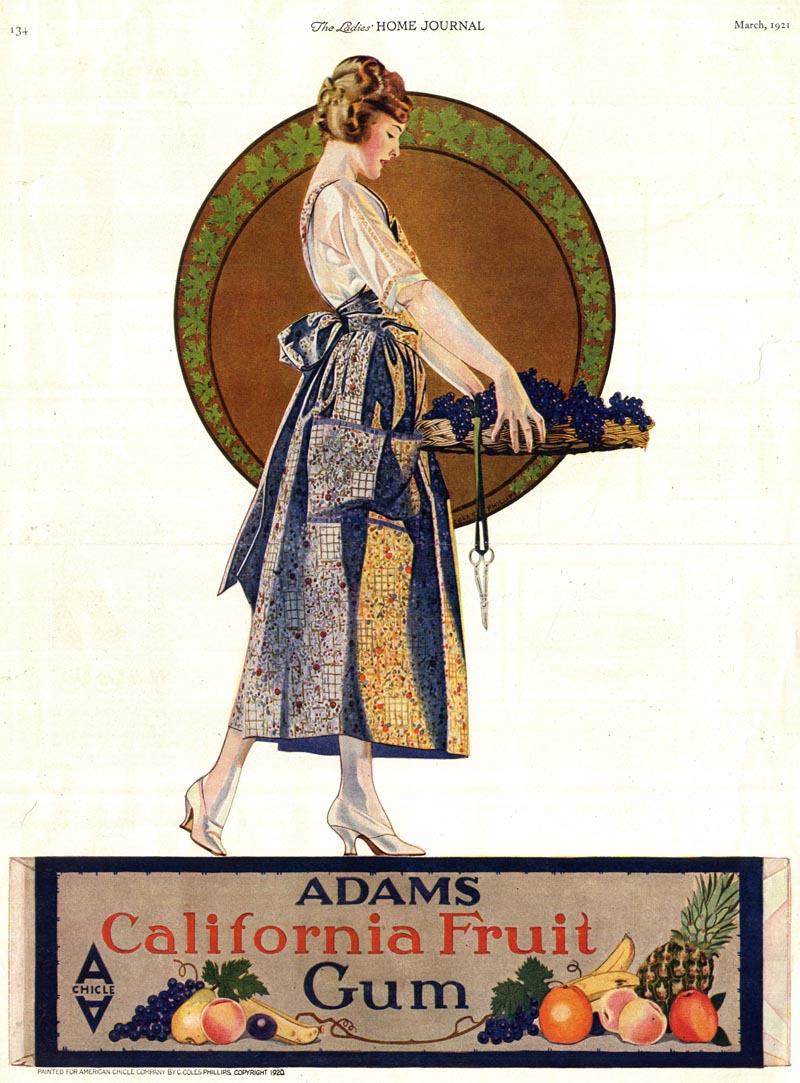

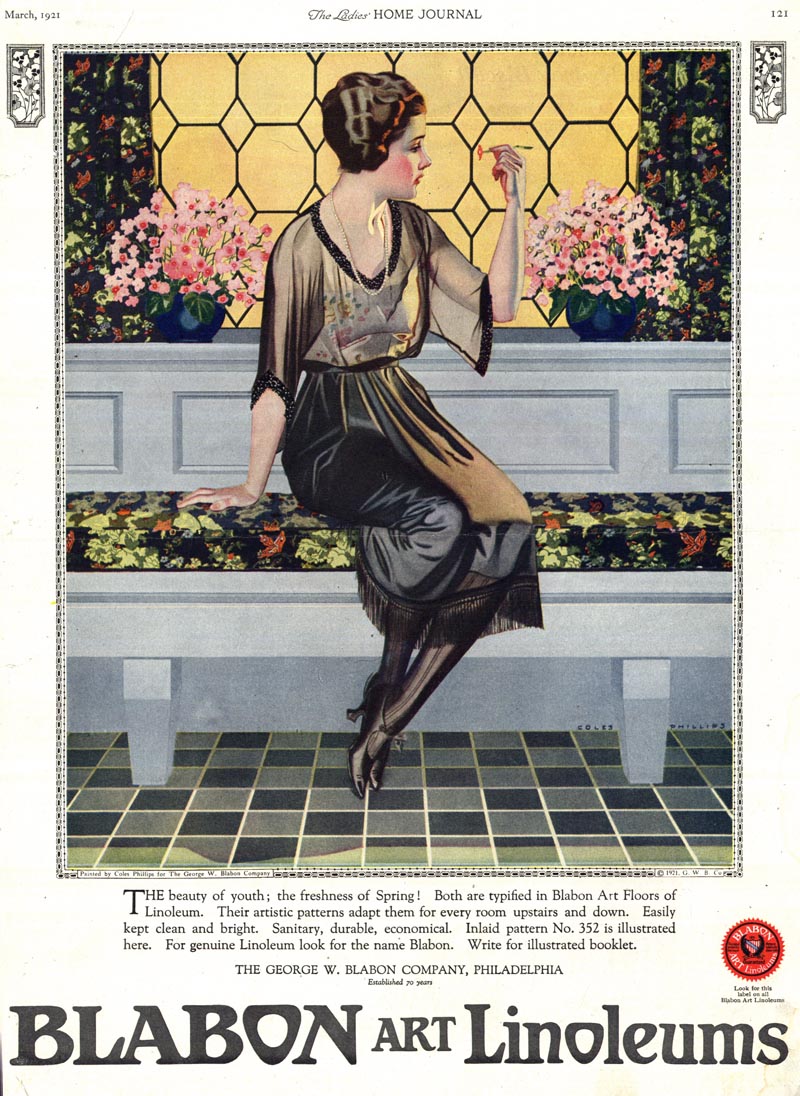

"Coles never painted anything but pretty girls. He used to get marvelous prices for his work, as much as, if not more than, any other illustrator."

"First he'd think of the best price he could hope for; then he'd think of his four children and add four hundred dollars. In the twenties he received two thousand dollars a picture, which was fabulous."

"Coles didn't decide to be an artist until he'd finished college. And he'd already decided that he was going to make a hundred thousand dollars before he was thirty-five. As he was a very smart fellow (I always felt he would have risen far whatever line of work he'd chosen), he did become an artist and he did make a hundred thousand dollars before he was thirty-five. (And he married a very beautiful girl, too)."

Using our handy inflation calculator we can quickly determine that Coles Phillips made over 1.2 million dollars from his art before he was thirty-five. His 1920s illustration fee of $2,000 would be over $23,000 today.

At that same time, Norman Rockwell was himself beginning to earn some very decent money. He describes one ad campaign he began in 1921 - a series of twelve paintings for Orange Crush - which paid him $300 per painting. While nowhere near the kind of money Coles Phillips was earning, it was a very good fee at a time when the average family income was only about $1,200 per year. "It seemed like such a lot of money that I couldn't resist." wrote Rockwell. And Orange Crush was only one of his advertising clients at that time. He was also receiving assignments from Willys Overland car Company, Fisk Bicycle Tires, Coca-Cola and Jello.

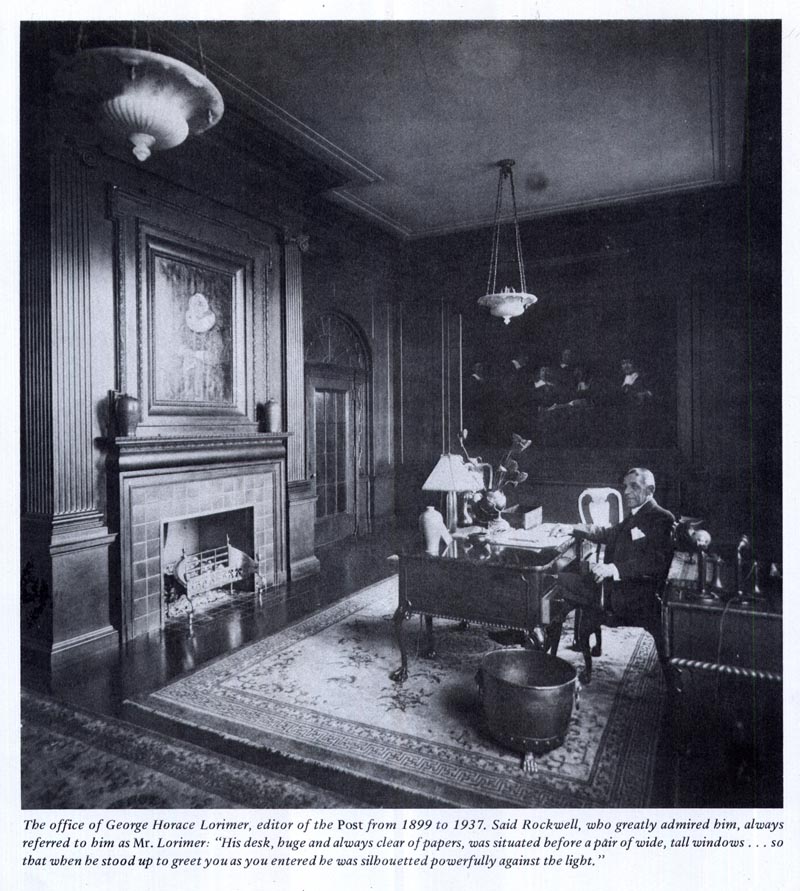

Besides all this ad work, Rockwell was doing magazine illustrations and covers for many magazine clients, most famously for George Lorimer, the legendary editor of the Saturday Evening Post (shown at his desk below).

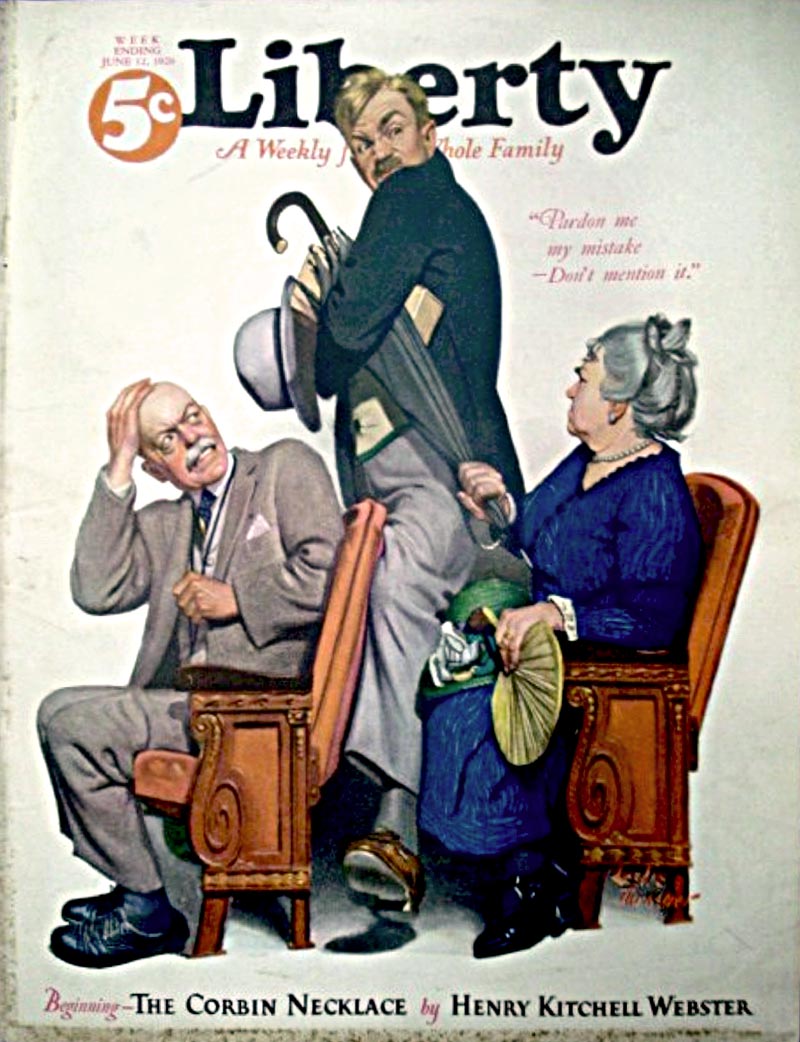

In 1924 the art director of Post rival, Liberty magazine, came to Rockwell's studio to offer him double the fee he was getting at the Post if he would jump ship. Because of his strong sense of loyalty to Mr. Lorimer, Rockwell refused. But his wife insisted that he confront Mr. Lorimer and insist on a substantial raise. Rockwell had been illustrating covers for the Post for eight years at that point and his fee, $250, had never risen more than nominally. When Rockwell visited Lorimer and described the situation with Liberty magazine's offer, Lorimer doubled his rate. He also advised Rockwell to charge his advertising clients twice his Post cover rate.

Its not surprising then that, at a time when the average annual family income was just over a thousand dollars, Rockwell describes being able to put ten times that amount into savings in a matter of months.

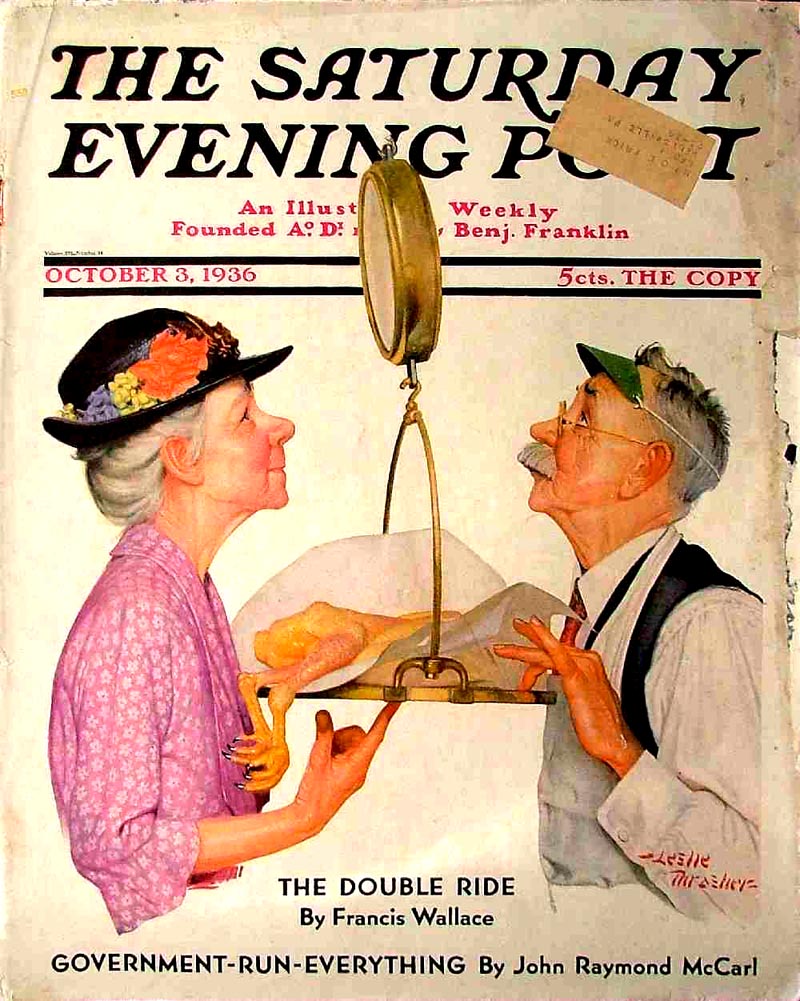

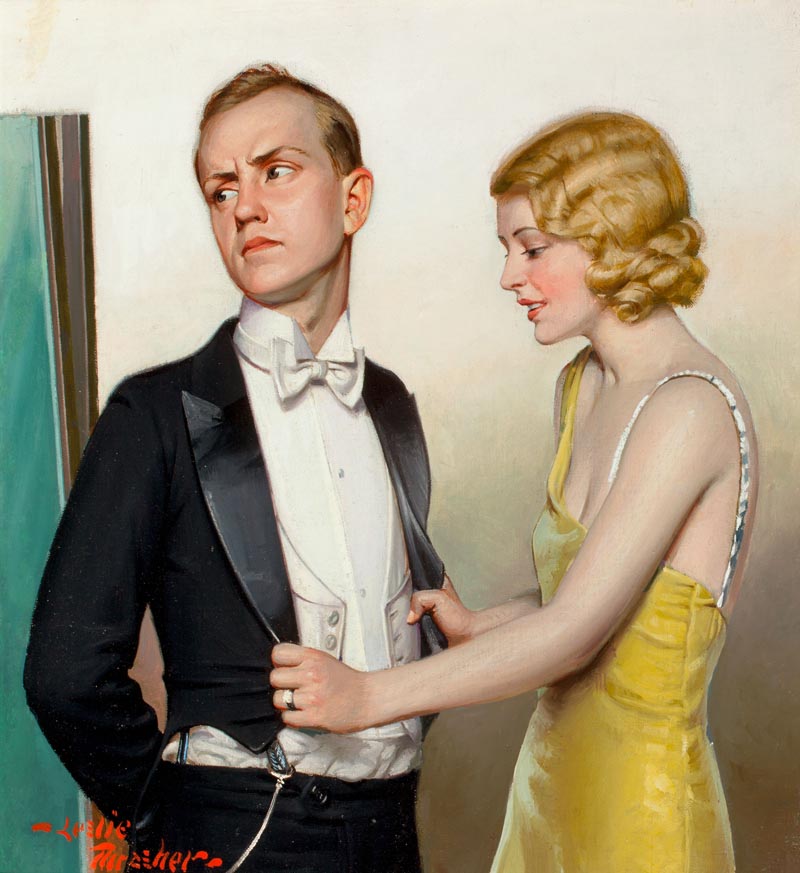

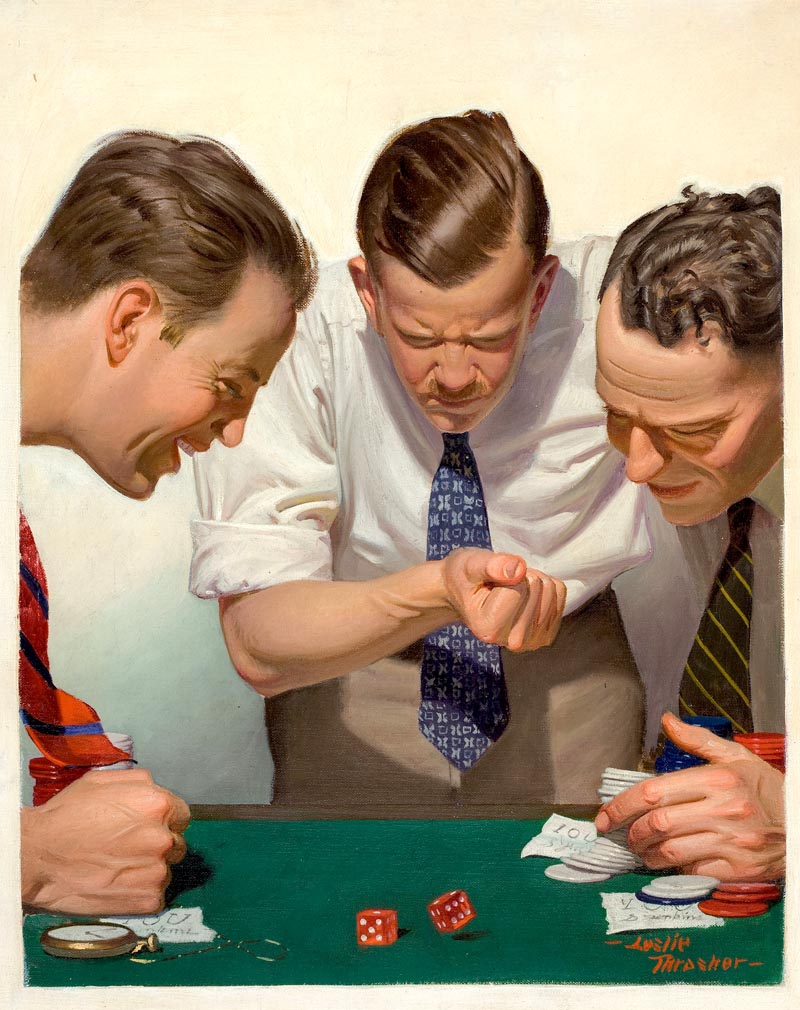

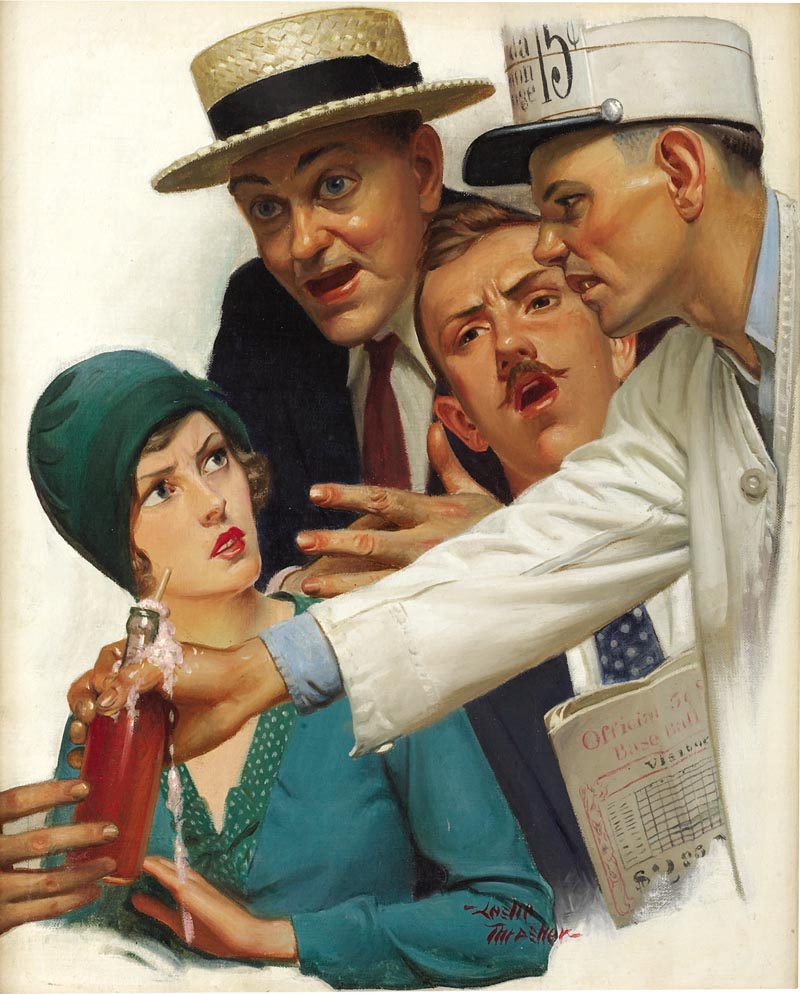

Liberty magazine's publisher may have failed to sway Norman Rockwell's loyalty to George Lorimer and the Saturday Evening Post... but the demon of temptation proved too powerful for another illustrator - Rockwell's friend, Leslie Thrasher. Rockwell writes that Thrasher "painted one of the most famous Post covers ever published. I still get letters from people who think I did it. It depicts a lady and a butcher standing on either side of a scale in which lay a chicken. The lady was pushing up on the scale; the butcher was pushing down. The cover appeared on 3 October, 1936."

"Some months later Thrasher came to my studio asking advice about an offer Liberty magazine had made to him. It was a five-year contract calling for Thrasher to do fifty covers a year at one thousand dollars a piece. "I can live on ten thousand dollars a year," said Thrasher, "so I can save forty thousand. At the end of five years I'll have two hundred thousand dollars. I'll be well off and secure for the rest of my life."

"I told him I didn't think he or anybody else could do fifty covers for even one year, let alone five. "Don't accept," I said. "You'll work yourself to death. And after the contract runs out, what'll you do? Nobody else will want your stuff." Well, he didn't know; maybe maybe it wouldn't be so bad; he thought he'd give it a try. And he went ahead and signed the contract."

"Liberty dreamed up a family around which Thrasher was to build his series (I forget the details; mother, father, children, and grandparents - something like that), and he set to work. One cover a week. He didn't last a year."

"After eight or nine months his house burned and he was so run-down and tired from overwork that he caught pneumonia and died."

"But the poor guy would never have lasted the full five years anyway. No man could have. Fifty covers a year? That's just too much."

"I still hesitate a bit between yes and no when somebody offers me a fat contract. Then I think of Leslie Thrasher and I can't say no quickly enough. security is very nice, but not if you have to kill yourself or your work to get it. Same with money."

* The text quoted today, the Norman Rockwell orange Crush ad, the photo of George Lorimer and the third Coles Phillips illustration are all from the book, "Norman Rockwell - My Adventures as an Illustrator" ©1979 Curtis Publishing Co.

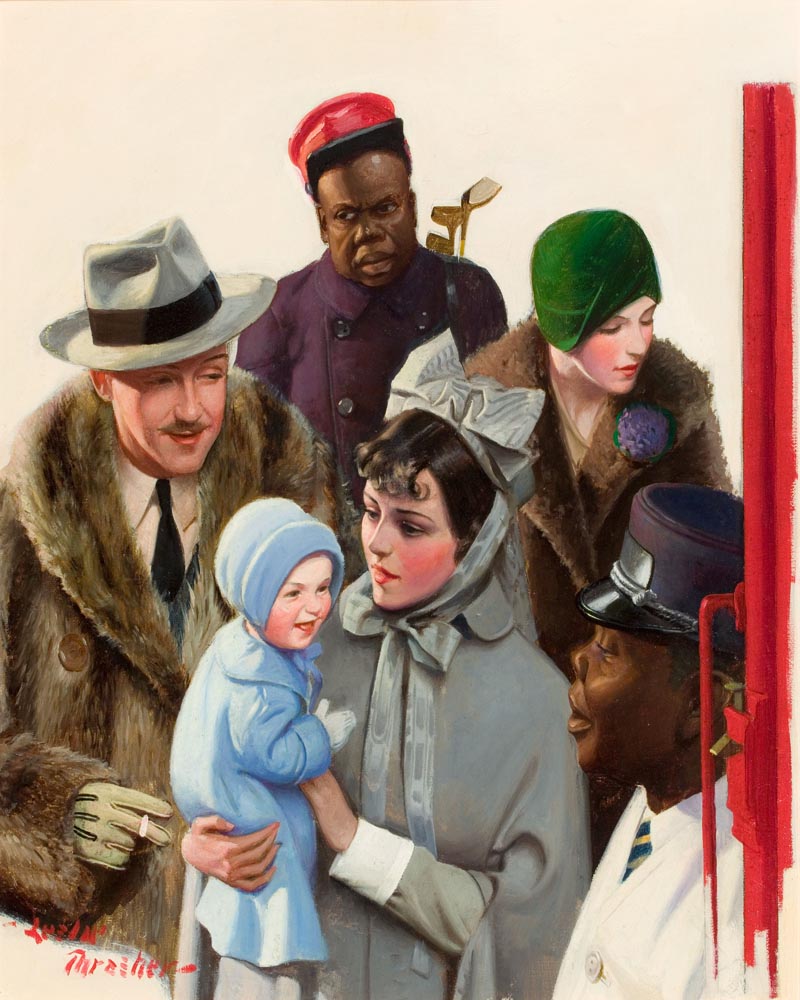

* Thanks to Heritage Auctions for allowing me to use several of their scans of Leslie Thrasher originals in today's post.

* The scans of Thrasher's Post cover was found at mymags.com

I'd love to know what's happening in the picture with the baby. Are they in a lift (elevator)? On a bus? Are the well-dressed couple married? Is the man in the background carrying golf clubs (for the well-dressed man)? Is he frowning cos the WDM is leering at the nurse? It seems rather subversive as the baby is smiling at the black liftman/busdriver. Is this all a complete fantasy?

ReplyDeleteInteresting post!

ReplyDeleteI know Rockwell had nightmares over that Crush series; giant pop bottles pounding him into the ground, but I never knew that about Thrasher -- how sad. Illustrators are artists, but to everyone else in the biz, they're just "vendors". Push it too hard and you suffer for sure (but I have to admit, if someone offered me the 2011 equivalent of $50k for 50 covers in this economy, I'd probably be tempted to give it a shot).

ReplyDeleteExcellent.

ReplyDeleteSimply excellent.

Richmonde;

ReplyDeleteI have it on good authority that the scene is intended to be a passengers boarding a train with porters.

Jil Casey and Saarer; thanks for your kind words :^)

ReplyDeleteEric; That's right! Rockwell wrote that he woke up from nightmares screaming "Orange Crush! Orange Crush!" He hated having accepted the assignment.

ReplyDeleteI can empathize why just about anybody might be tempted to take a shot at such a lucrative contract as the one Leslie Thrasher signed with Liberty magazine. I had my own much smaller version of something like that years ago and it also turned out disasterously ( happily, I didn't die ... but I did lose my shirt and a lot of sleep). I think that's the real wisdom Rockwell proffers: if it seems too good to be true, it probably is. ;^)

Do you know how old Leslie Thrasher was when he died?

ReplyDeleteGreat post....I enjoyed this one a lot.

ReplyDeleteChoice post Mr. Peng.

ReplyDeleteGreat art and a tragic & poignant point... The breaking point between insane deadlines and temptation is well illustrated, no pun intended...

Great post, Leif. Loved it! I read Rockwell's bio about four years ago on a trip and couldn't put it down. It quickly became one of my favorite books of all time.

ReplyDeleteRockwell threw a few "cautionary tales" in that book. The tragic end of Leslie Thrasher as well as the dark tale of the Leyendecker brothers. They just don't teach that side of illustration in art school. I wish they would have, though. Seeing the titans of the golden age as human beings, with struggles and foibles, makes it so much more real.

Daniel; I think Thrasher was 46 or 47 when he died.

ReplyDeleteThanks Jared, Will and newleafcreative. You're right - they don't teach this - or didn't - I was certainly oblivious to it when I went to art school...

ReplyDeleteBut I get the impression that now, with the Internet making all of info so much more readily available, more young people are aware of the history of the business than ever before.

Quite a few educators have contacted me over the last few years to let me know TI is required reading in their courses. Very gratifying! :^)

A cautionary tale indeed. To commit himself to such a workload was never going to be a good move, however tempting.

ReplyDeleteIt's certainly a cautionary tale. Illustration House's biography of Thrasher tells a rather different story - that Thrasher didn't just quit after one year - he DID do them - weekly - for SIX years. If that's true, how could he have been anything other than a classic case of burn out?

ReplyDeleteThrasher bio:

http://www.illustration-house.com/bios/thrasher_bio.html

Part of the ailing of American commercial art came, in my opinion, from the 1913 Amory Show in New York. Seems from then, America's fine art (illustration) began to be undermined at the top as not sophisticated enough or too literal. Then, as Norman Dodd discovered, you have large foundations undermining our foundations as well. During the '30s the art director was being born and many were EU transplants. Nonetheless, this is wonderful and informative blog.

ReplyDeleteMichael;

ReplyDeleteWow, that's very interesting! I wonder why the disparity in stories... I'll ask my contacts at the Norman Rockwell Museum - perhaps they can clear that up for us.

Coles was a remarkable water colorist and his nearest 'rival' might have been Ludwig Hohlwein of Germany. Both men were aware of one-another.

ReplyDeleteHad the first world war not happened and Coles lived, what a meeting of the minds and brushes it could have been.

Coles painted pretty women, but also very modern ones I can easily imagine, had he lived longer, Hollywood seeking his services for the Jean Harlows, Hepburns, or Bette Davises just over the horizon.