Minutes of a 1936 Society of Illustrators Meeting

"From $2,000,000 to $3,000,000 a year is being paid to illustrators by these ten mags:

SEP, Collier's, Liberty, Cosmo, American Mag, Good House, Ladies HJ, McCalls, Womans HC."

"From 20 to 25 men and women are making between $50,000 and $100,000 a year. From 50 to 75 men are making between $25,000 and $40,000. 100 are making $15,000 to $20,000"

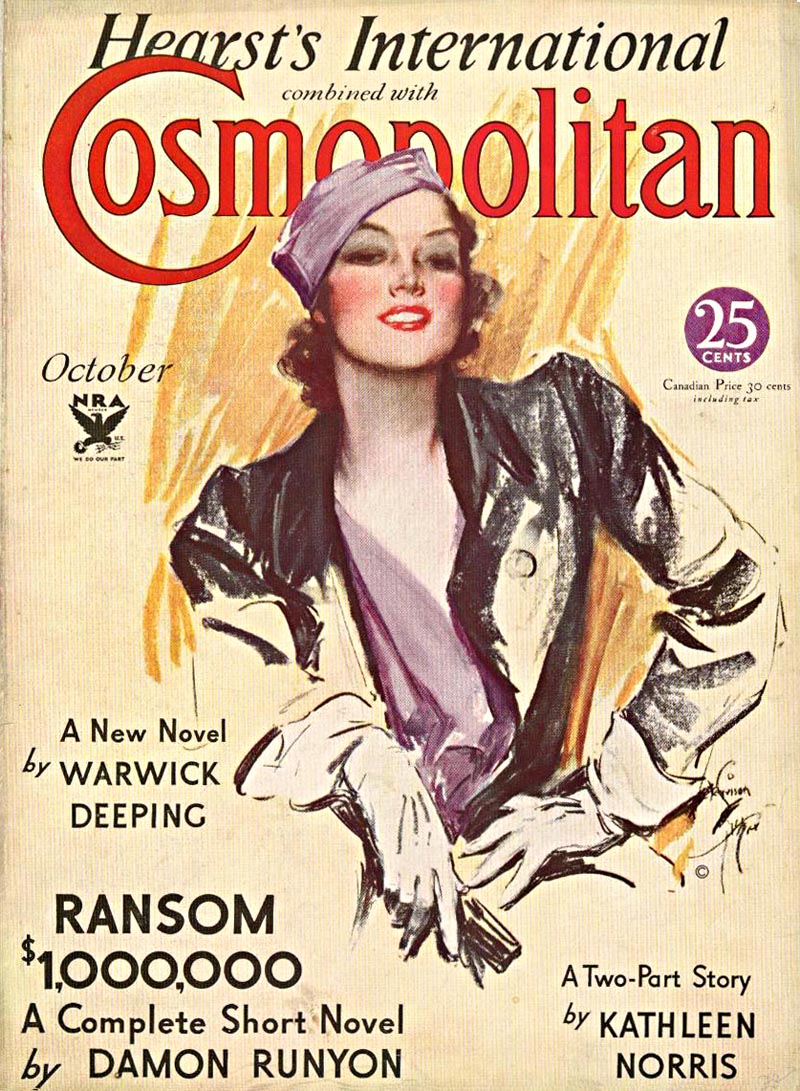

Harrison Fisher, $3,000 per cover Cosmo.

McMein, $2,500 per cover McCalls.

Rockwell, $2,500 per cover.

"10 men get $1,200 to $2,000 per single illus."*

That was the '30s... and from a recent post we now know that Al Dorne and the other top illustrators of the 1950s were getting $1,000 to $2,000 for a story illustration. If that last statistic from 1936 is correct, it would seem that the best price per story illustrations had remained fairly static for decades even before the mid-century.

Here are some more anecdotes related to me by artists (or their family members) that speak to both pricing and some of the similar circumstances experienced by different illustrators as the '50s drew to a close - what could be called "the end of the last Golden Age of illustration."

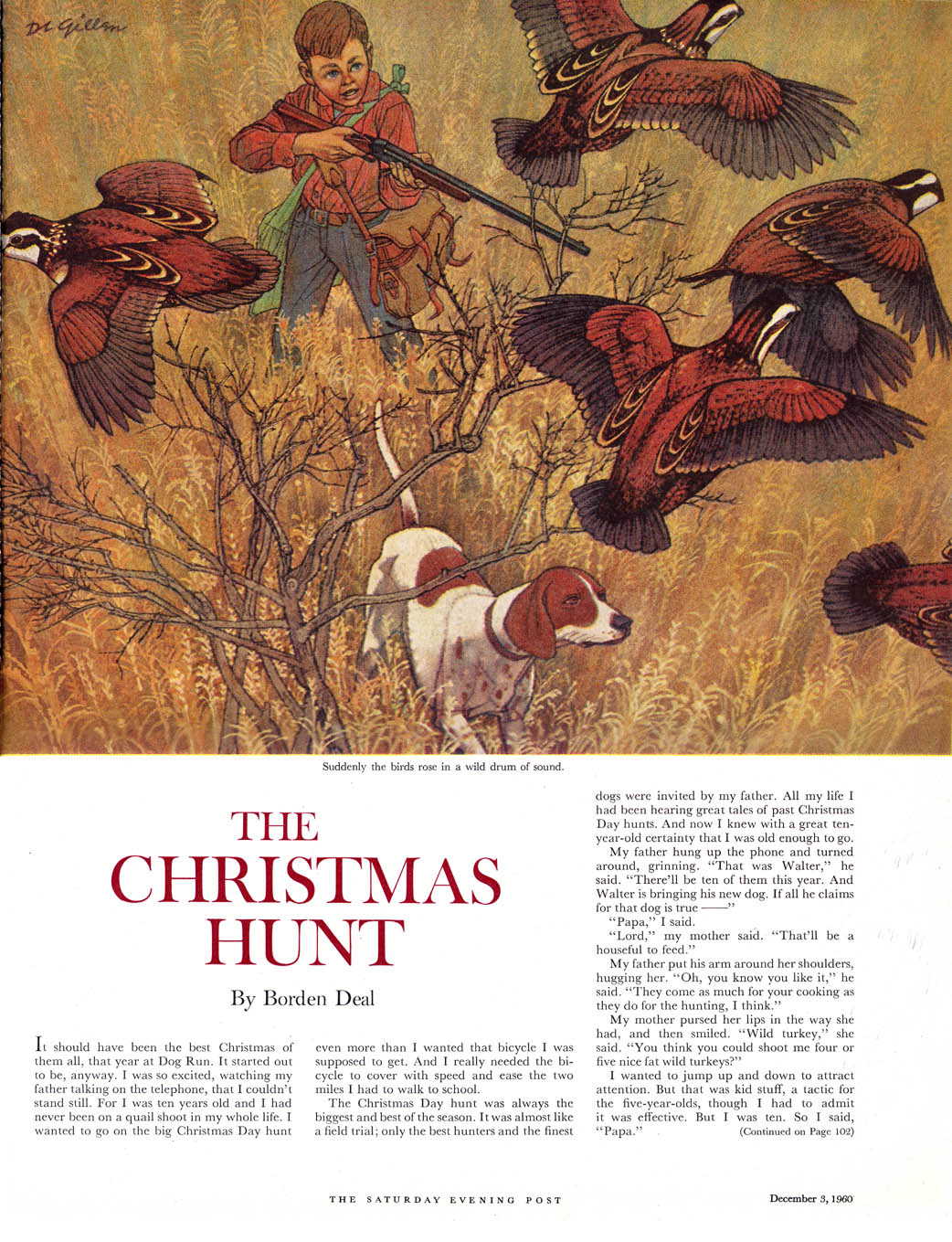

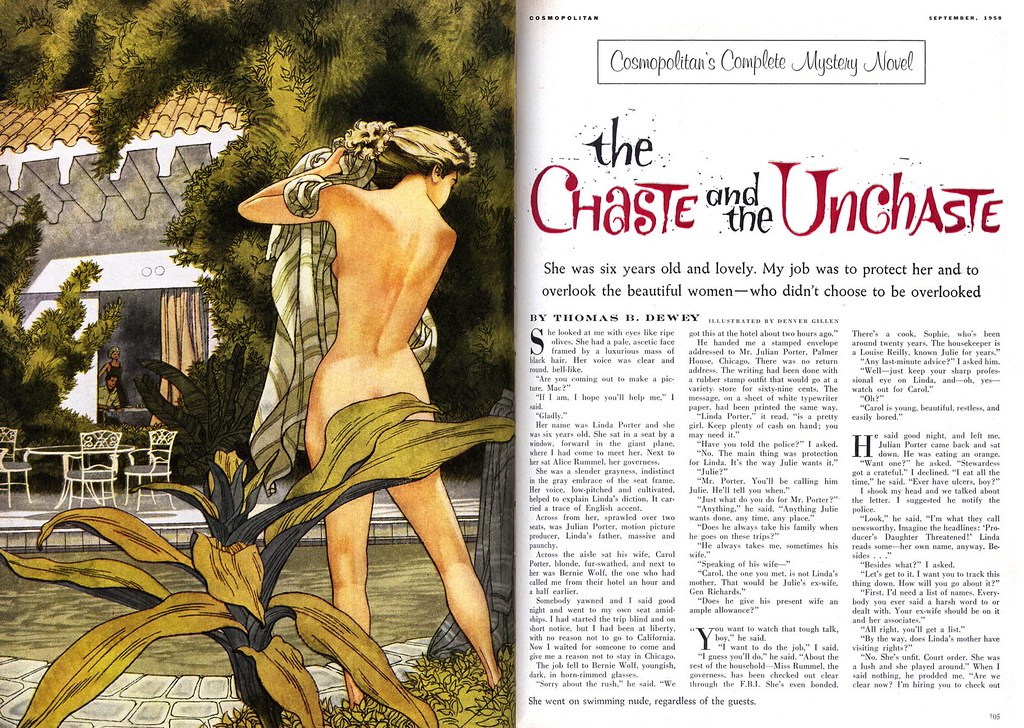

Jenifer Gillen on her step-father, Denver Gillen:

"Pop was very concerned about the growing tendency by magazines, even in his day, to use photography as a way of illustrating stories."

"He was aware that there was a growing trend that was narrowing the opportunities for the illustrator. I can't remember exactly when I first heard the conversations, but it was probably before I went to Boston University."

"I do remember that Pop had been doing quite a bit of textbook illustration (for Ginn & Company, I think, and others). This was while I still lived in at home in Connecticut, so that would have been in the late 50s, early 60s. And, he did not enjoy this type of work; very boring."

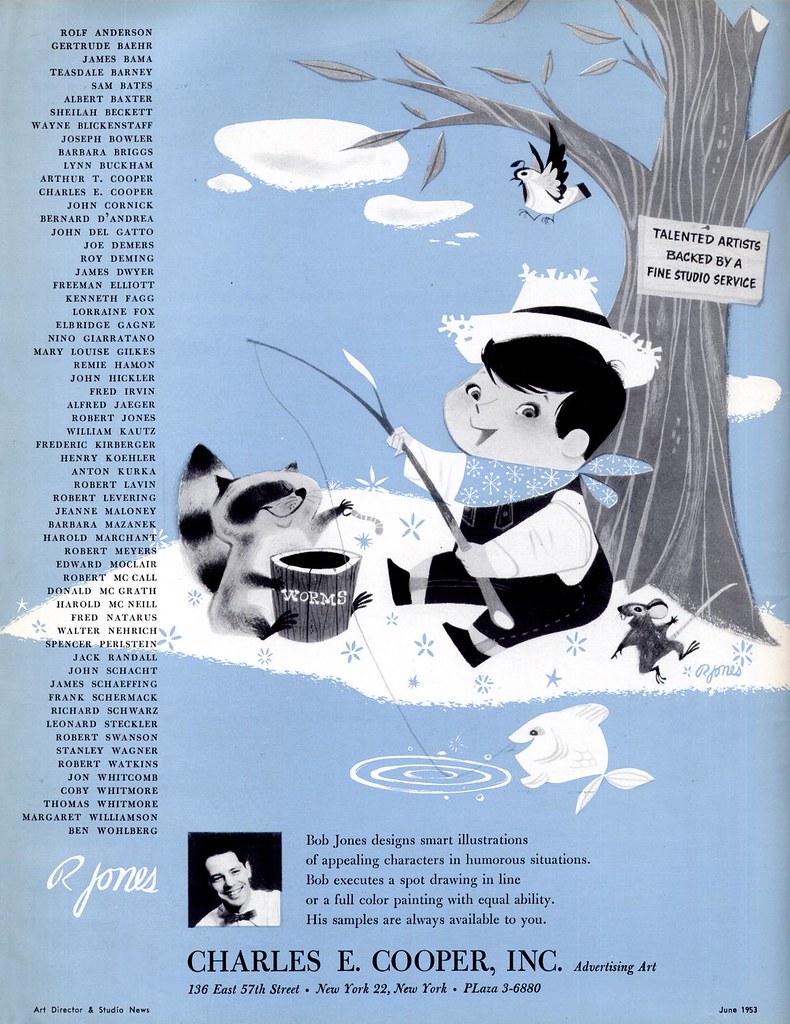

Bob Jones on his time at the Charles E. Cooper studio:

"Chuck said, "How much do you want to make?" And I said, "Gee, I dunno... um.. sixty bucks a week?" and he kinda snickered. He said, "I'll start you at a hundred a week." and I damn near fainted. That sounded like all the money in the world!" Bob chuckles, " A hundred bucks a week was a big deal then, in 1952."

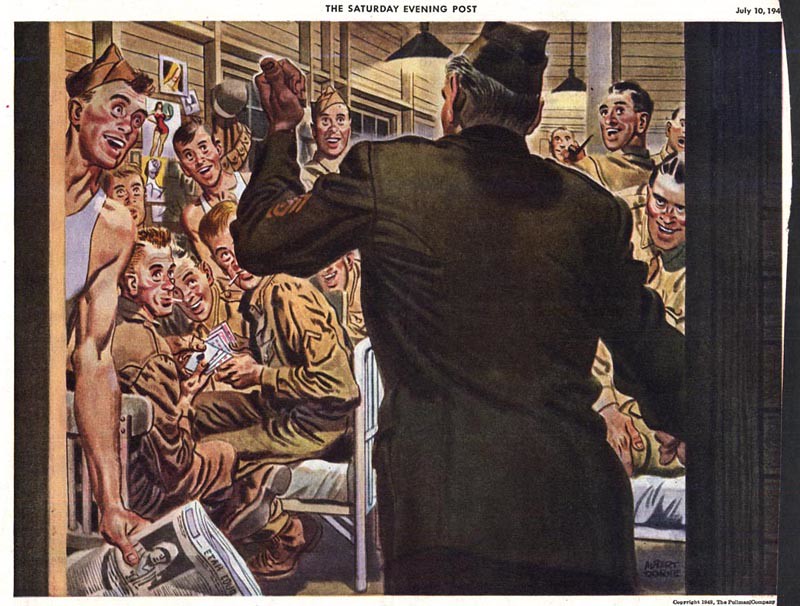

After a year or two, Chuck Cooper would change the arrangement with his artists. As they became established, the studio would split the commission on advertising jobs 50/50 with the illustrator... but all were encouraged to try to get editorial (story) assignments - and Cooper took none of that fee at all. Bob got his first big Saturday Evening Post job (below) in 1955. He explained to me that the Post paid $1,200 for a double page spread - quite a jump in pay from a $100-dollar-a-week salary.

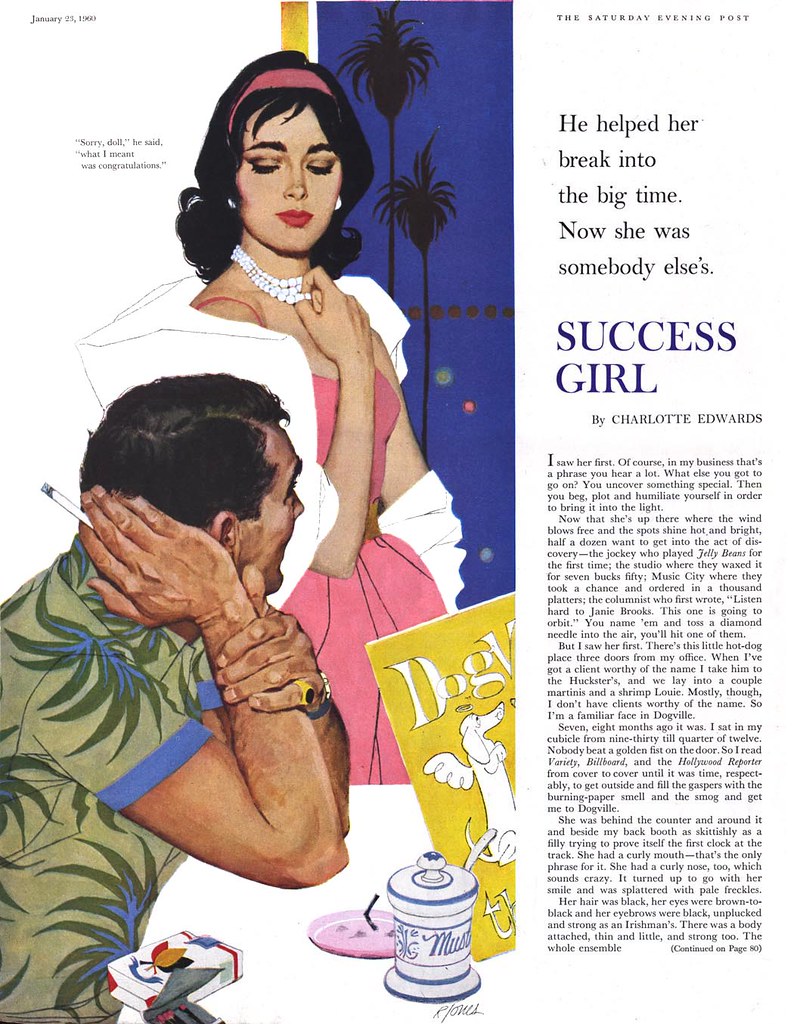

For the next couple of years, around 1960 - '61, the Post became a steady client for Bob's romance art. "The Post paid $600 for a single page illustration," he says, "but I tell ya, after you paid your modelling fees and all that, $600 didn't go very far."

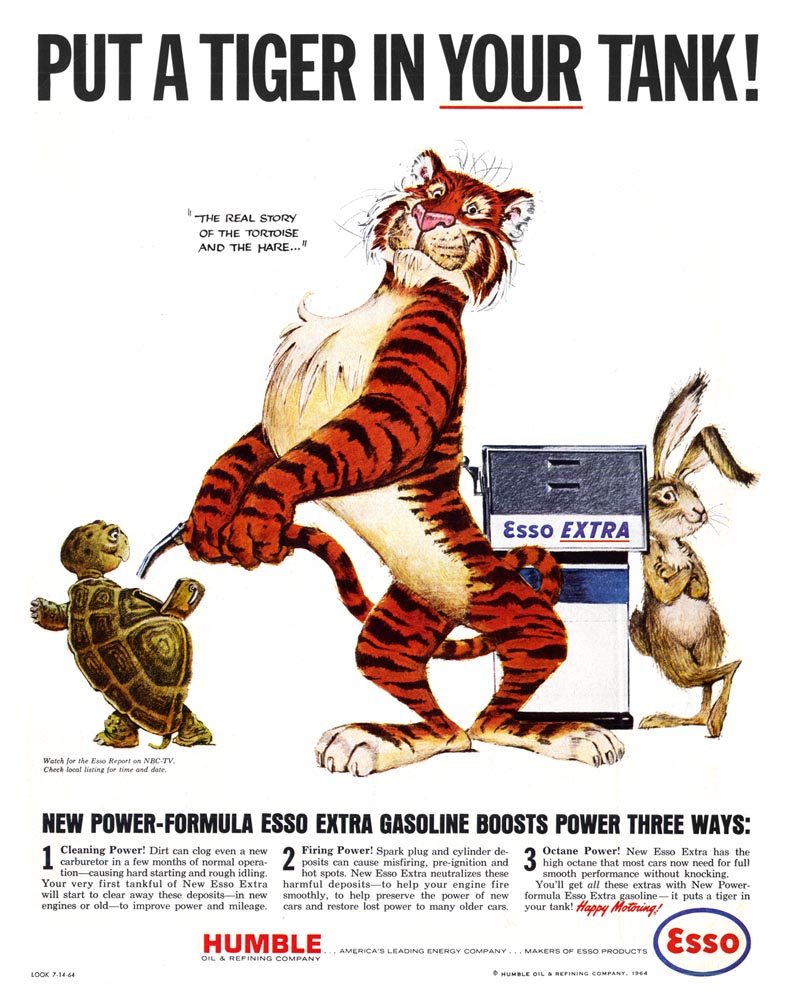

A few years later: "It was 1964," Bob begins, "and I was working at Cooper's. One of the salesmen came to me and said, "Exxon wants a tiger."

After his design had been chosen: "Well, I was kind of with Chuck at the time (when I did the initial sketch)... and then we didn't hear anything... and then I had left Chuck, because work had really fallen off at the studio. And then all of a sudden the Exxon stuff started pouring in."

"One day it occurred to me... I had started this when I was with Chuck, and it was advertising work. So I said, "I owe Chuck some money." So I went to him... and I can't remember what it was exactly but in a couple of months I made something like eight thousand bucks. And I went to give Chuck half of it... and he wouldn't take it."

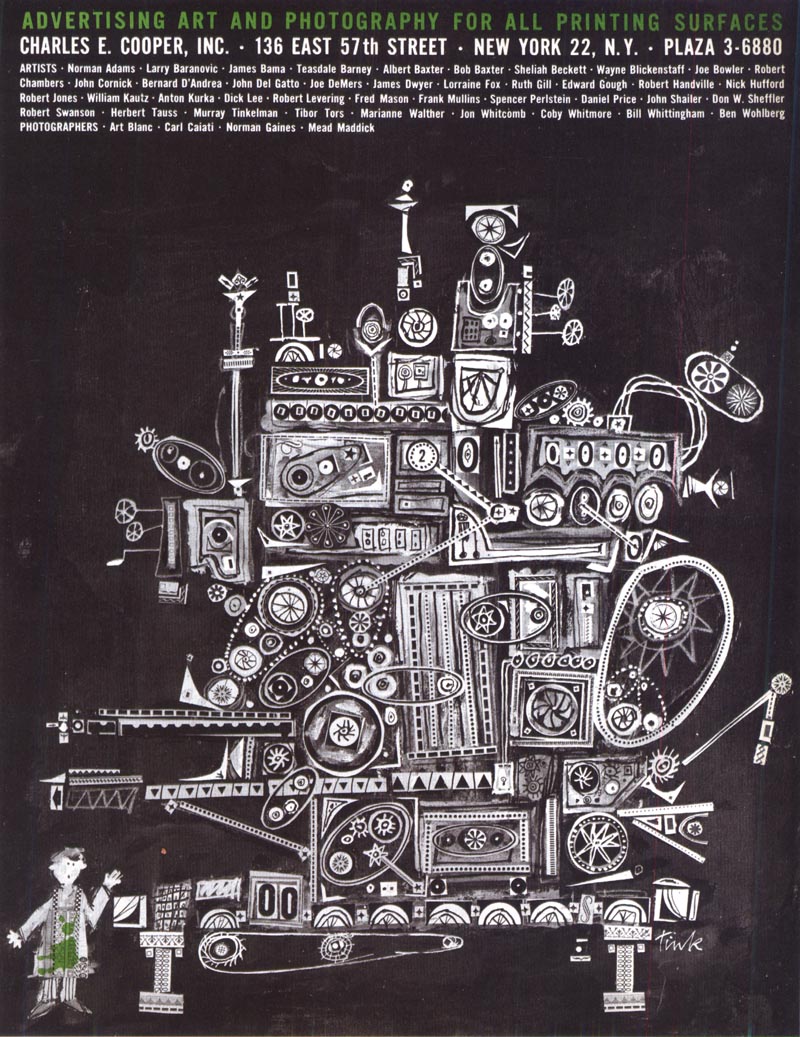

Murray Tinkelman on his time at the Charles E. Cooper studio:

[Around 1958] "One of the salesmen came in with a job from the Grollier's Society. They were publishing an encyclopedia for high school kids. And I got $1,800 for that one job, which was as much as I had made the entire previous year. That was a break-through. I don't think I was ever in the red again after that job... there was always something on the board, there was always a cheque in the mail."

"Fast forward for a minute here: there was a point in 1961, when I did my first Saturday Evening Post job. And it was a thousand dollars for one painting."

"And I went into Chuck's office and I gave him a cheque for five hundred dollars. Now Chuck did not take any money from editorial jobs -- he only took money from advertising -- and this was an editorial job. He said, "What are you doing?" and I said, "Well, you staked me to that draw." And he said, "Well can you afford this?" And I remember saying ,"I can't afford not to do this." So he took the cheque - reluctantly."

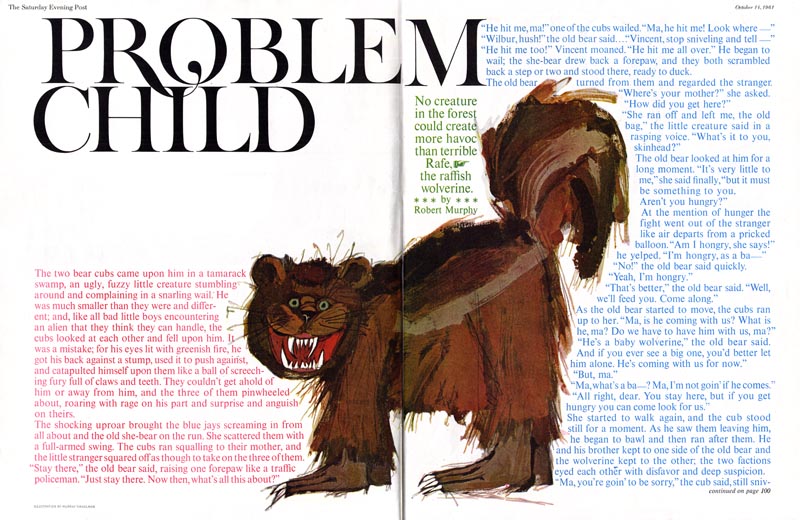

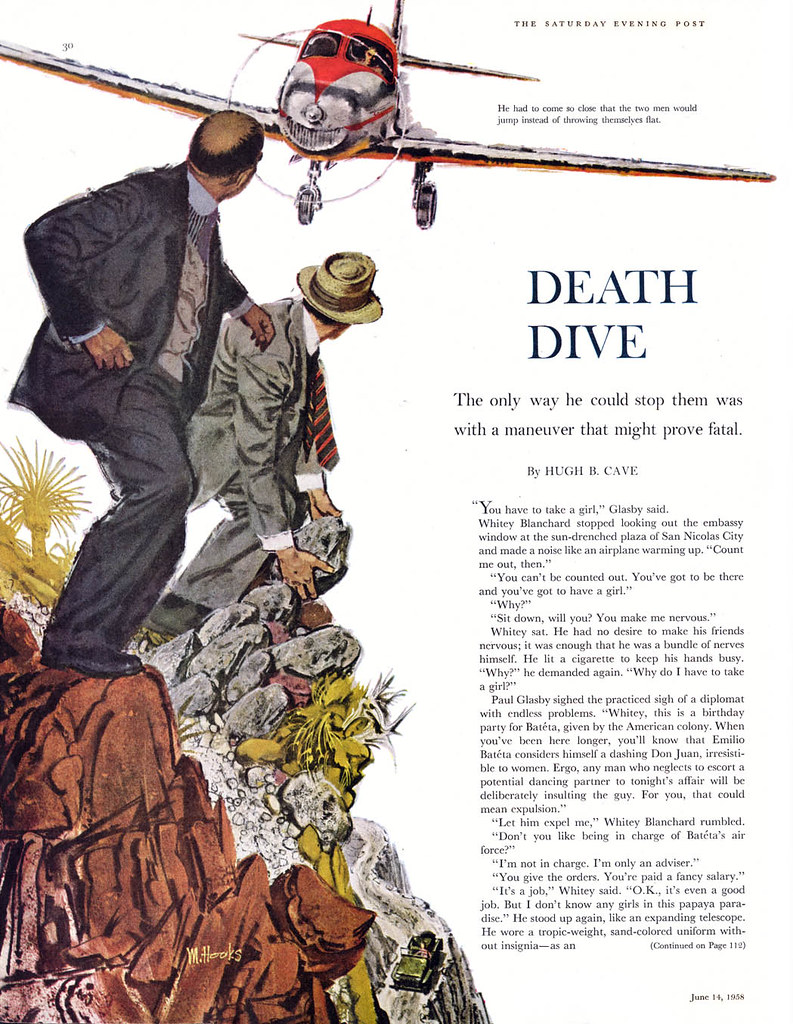

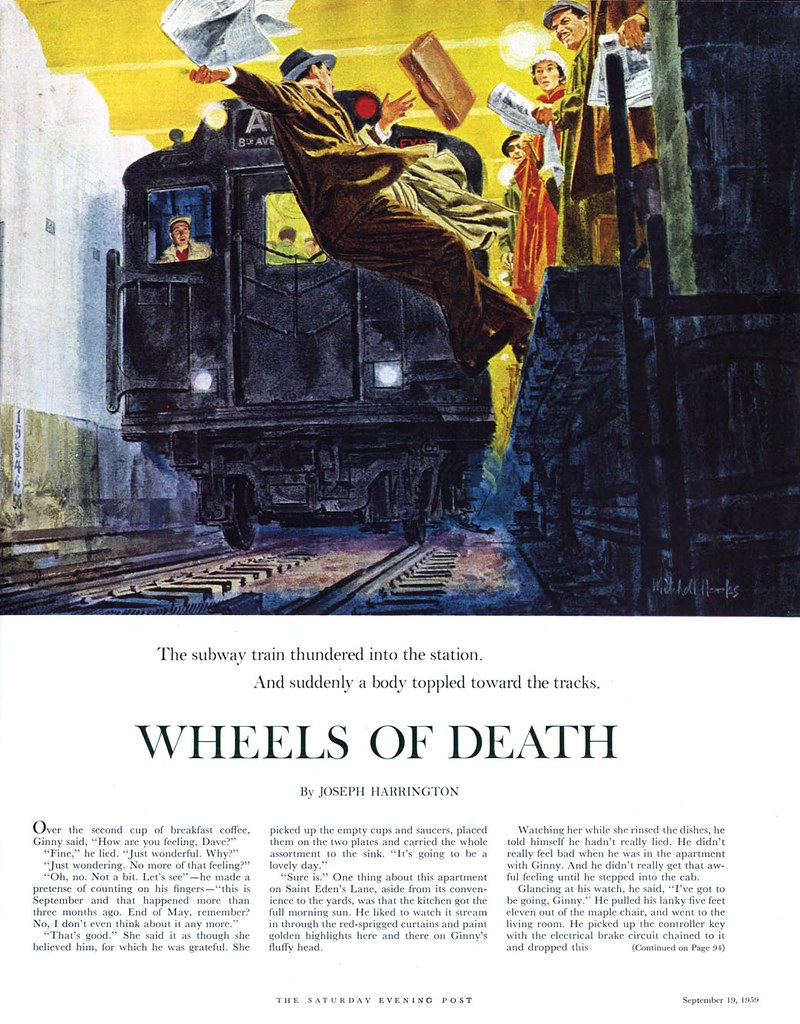

Mitchell Hooks:

By blazing a trail in book cover illustration instead of following in the footsteps of others, Mitch was at last noticed by the magazine art directors. In the late 50's, his work began appearing in the pages of The Saturday Evening Post. It wasn't everything he'd hoped for.

When I asked him about working for the The Post, surely the pinnacle of achievement for any illustrator in the 50's, his response was less than enthusiastic.

"They paid very poorly, considering their stature. About $300 for a full page illustration - the same as what I was getting for a paperback cover. And they acted like you should be honoured they'd chosen you."

I asked him if it would be fair to say that ad art paid as much as ten times what the editorial did, and he said that sounded about right.

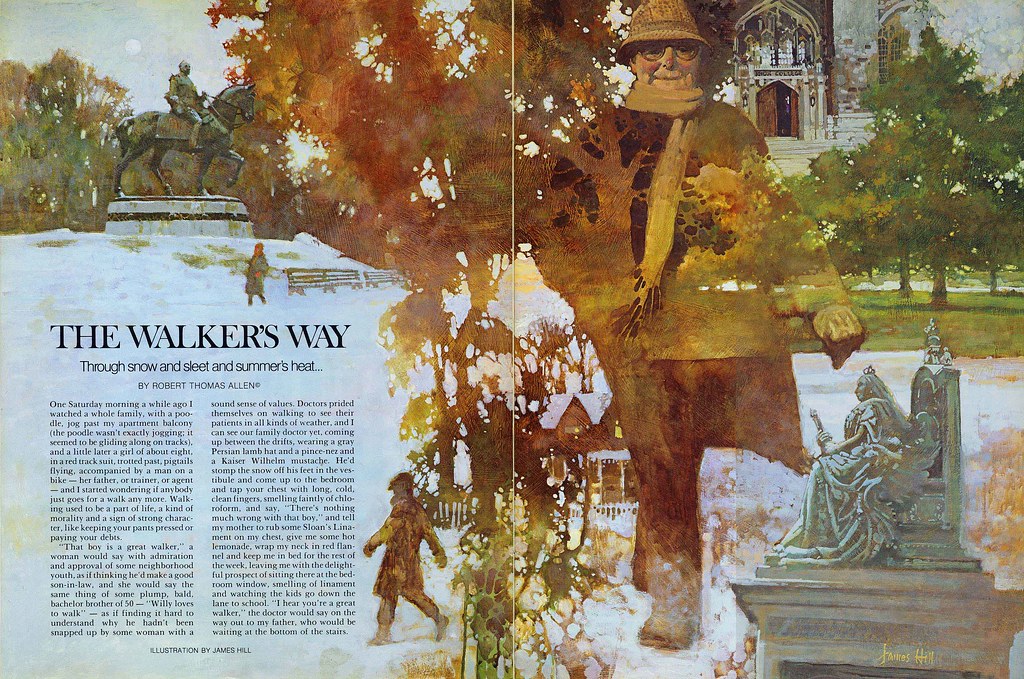

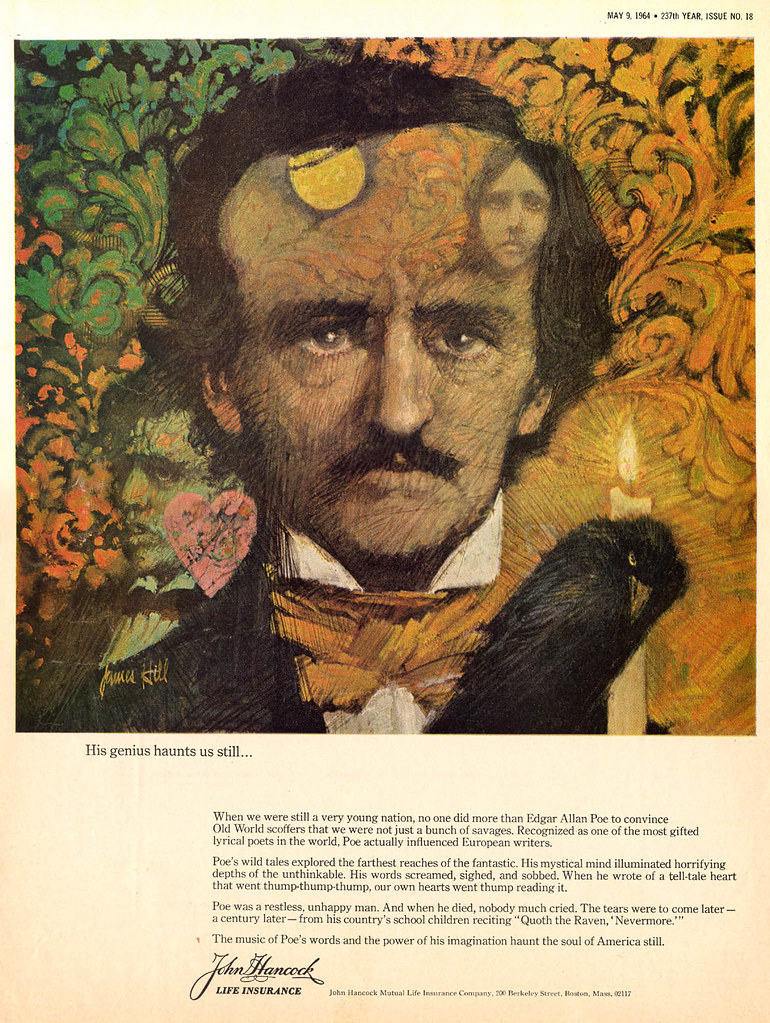

Excerpt from the March 1978 issue of Creativity magazine on James Hill:

[In the 1950s] "The major magazine market was the proving ground and it also held the prospect of diversified markets for illustrators. If Al Parker could pull in $2,500 for a page or spread, James Hill was willing to take the risk and compete for those rates."

[But] "the continuous financial upheavals in the magazine industry and other gradual changes in the New York scene eventually pushed Hill into the decision to return to his first base of operations [Toronto]. Hill reasoned that what with inflation, a reasonably healthy magazine profit picture and his own improved capability the rate for magazine illustration should be at least double of 15 years ago. He was wrong."

"The price of everything else may be up but fees to magazine illustrators have not risen (in fact, when at the time Hill returned to Toronto, fees were actually going down)."

Anita Virgil on her late husband, Andy Virgil:

"The 1960s were another kind of turning point in illustration art. Fewer pieces of fiction appeared in the women’s magazines. Usually there were at least three per issue. Photography was in the ascendancy, competition among the illustrators was stiff for the two per issue stories, then one per, and then even this well pretty much dried up. And later, when there was an upswing in art, it had evolved into quite different kinds from that of the ‘50s. Even advertising art was heavily using photographers."

Most New York illustrators saw the writing on the wall and gradually turned elsewhere to try to make a living in this new environment. I know few firsthand details of how others with Rahl studios managed except that Fred Siebel became an art director, Herb Saslow sold mutual funds and exhibited some of his surreal romantic paintings to a Pennsylvania museum. Spot man, Oscar Barshak always had depended primarily on his interior decorating. Dorothy Monet would undoubtedly come out on top . . . of whatever she chose to do. Just prior to that time, though, I think she had married a psychiatrist and had a baby. This downturn in illustration likely had little effect on her.

I know there was some work coming in early in the ‘60s, but it was the barest minimum -- the jobs too few and far between. In 1964, Andy was approached by an agent dealing in second rights for the European market. They paid very little -- but they paid.

During the remaining years of the 1960s, Andy was trying all sorts of things to get by as well as to keep himself occupied. He practiced his trumpet, took lessons in N.Y. with Roy Stevens. By 1968, almost nine years of unabated hard times under our belt, together we started teaching art classes in our basement – just to put bread on the table. Andy continued to paint samples [and] took them around New York to try for work. He even tried doing some storyboards. Colored inks on bond paper. Funny little commercials he dreamed up.

For a while he was represented by Artists, Inc. and by Artists Associates but still, not very many jobs came of these affiliations. Those that came from Trans World Feature Syndicates paid ever so little for 2nd rights. Once we received a request from a magazine in South Africa. Hard-up as we were, we refused to allow them to use Andy’s work because of their long policy of apartheid.

By 1974 and for the next four years, I had to work full time while Andy served as house-husband. And he kept painting samples. Enter Joe Mendola. Andy’s last rep. It was somewhere around 1978 and suddenly the clouds lifted. The siege was over, somehow, and there was work coming in just as it had so many years before.

Tomorrow: After the Siege - How Mid-Century Illustrators Adapted to Changing Markets

* On October 26, from 7 to 9 pm, I'll be in Toronto at The Nook giving a talk about mid-century illustrators whom I've written about over the last six years. I'll share stories and anecdotes - some from my research but also many from personal interviews I've conducted with many Canadian and American illustrators of the mid-20th century. I'll be looking at changing styles and technology and how both have impacted the business of illustration over the last half century. Perhaps we can learn something from the lessons of the past... or perhaps we are doomed to repeat it.

Also, there will be treats.

If you think you might like to attend, the details are at The Nook Collective website

* If you'd like to try converting any of these numbers into current dollar values, here's a link to a handy online inflation calculator

This has been a highly fascinating series of articles, Leif. As a artist trying to piece paying gigs together in the marketplace today, I don't find these article discouraging at all. But rather, encouraging as there will always be someone who is willing to pay for art on some level. Yeah, an illustrator making Leyendecker or Rockwell will never happen again, but having a decent living for me and my family sufficed by creating art would be satisfaction enough. Thanks as always, Leif!

ReplyDeleteThanks Adrian; that's an excellent attitude - and one I'd highly recommend to anyone who leaves these posts feeling depressed. Tomorrow I hope to address how illustrators dealt with these changes, so perhaps that will be helpful to some readers.

ReplyDeleteI do think the decline in remuneration is something we illustrators need to acknowledge - and analyze - and use that information to our benefit. :^)

At the same time that the Post's rates for illustrators were diminishing, its rates for writers were diminishing too, because its advertising revenues were diminishing because its circulation was diminishing.

ReplyDeleteI promise that all of the writers, editors, printers, managers and even newsstand operators were going through the same distress as the illustrators. How could they feed their families? They couldn't get work at one of the other magazines listed in those 1936 Society of Illustrators minutes, because most of them were wiped out too in the same Permian extinction. The few that survived did so by abandoning any pretense of publishing illustrated fiction (better leave that to television). Cosmo changed from printing dozens of illustrations in each issue to printing photographs of designer lipstick and running articles about "17 new errogenous zones behind your man's left ear" (which I suppose counts as fiction of a different type). But at least they survived.

I hope this fascinating series of yours will follow through to the consequences of all this creative destruction. When Rockwell abandoned the sinking Post to start painting for Look Magazine, it freed him up to address civil rights and other issues he could not address at the Post. One of those important paintings is hanging at the White House today. Rockwell became free to experiment with a looser style, and did award winning work in his old age.

Meanwhile, the only lasting economic value remaining where the mighty Post empire once stood is the licensing value of Rockwell illustrations. The sharp dealers who bought the remnants of the magazine have made a fortune by exploiting the royalty value of that art.

Truly fascinating series, Leif. Rockwell's $2,500 translates to over $39,000 today! Per cover! Incredible!

ReplyDeleteIn many cases I'm pulling in almost half what I was making for a cover 25 years ago. The steady rate decline over the past decade or so is something I don't see reversing. If it weren't for after market sales of originals making ends meet would be tough indeed.

Thanks, Leif, for this really well researched study. It is sobering. How in the heck can we hope to put the time in to match those old guys when we're getting 1/10 or 1/20 of the prices they were getting?

ReplyDeleteOne upbeat side of this story is with original prices, which inverts the pyramid. As commission prices have gone down over the years, original values, at least for the top artists, have gone way up. Frazettas have recently sold for over a million and Rockwell's "Breaking Home Ties" sold at Sotheby's for 15.4 million. In those old glory days of high commission prices, great pictures were routinely sold for dirt cheap or just thrown out. An artist can make up the difference selling originals, something to keep in mind for a young artist deciding whether to go digital or not.