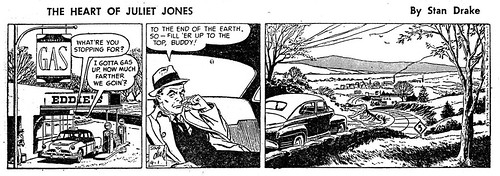

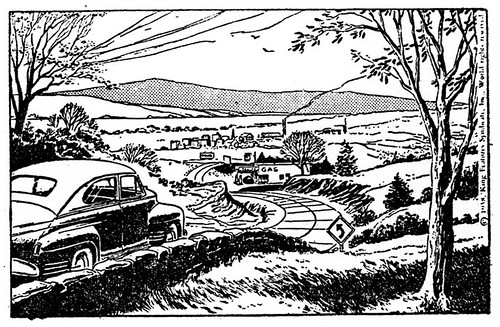

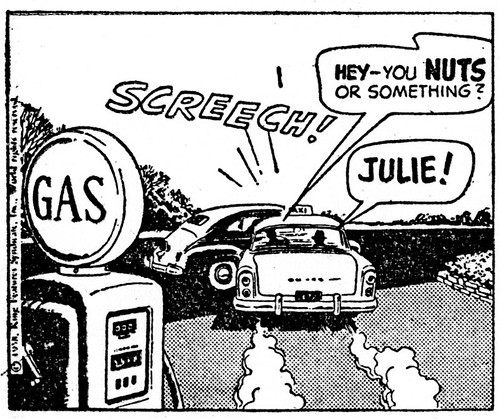

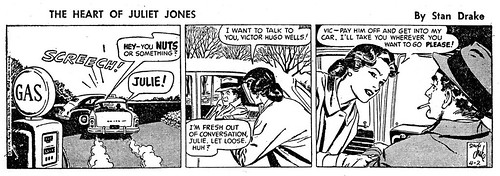

"During this period, I ghosted several weeks of strips for Stan Drake’s very popular The Heart of Juliet Jones,"

"...spending some time at Stan’s home in Westport, Connecticut, where I got a taste of the attractive lifestyle enjoyed in that community by cartoonists and illustrators, who seemed to comprise about half the population. In addition to Stan’s flamboyant, entertaining presence the area was crawling with such ‘bigfoot’ luminaries as Dik Browne, Ralston Jones, Frank Ridgeway, Mort Walker, plus noted illustrators Steven Dohanos, Harold von Schmidt, Noel Sickles and others whose work I had admiringly clipped out of national magazines such as The Saturday Evening Post since I was a kid. It hardly needs to be said that lunches with those I already knew, and a few I met via Stan, talking shop, chatting and joking with them, visiting their homes and studios, were tantalizing experiences for me. Glimpsing those artists’ lives markedly pointed up my own fish-out-of-water status among my New Jersey neighbors, most of whose lives seemed to revolve around sales quotas, expense accounts, and their golf game…"

"… I’d already decided we had to move to Westport."

"At the same time, while I remained committed to selling and authoring my own comic-strip, that goal had, in a sneaky way, become somehow less urgent. In part, I knew, it was because of my busy professional life, as well as the enjoyment of our little family and our attendant activities."

"But there was another element at work on a less-conscious level. That was my gradual absorption, via observation, of certain realities about such work, about the endless grind of actually turning out a daily, 365 times a year, comic strip. Resulting cumulatively from my exposure to, and working with these guys – and though I did my best to deny it, to dismiss much of it as the exception – I was picking up, inferring, a growing sense that it might not be the best way in the world for me to spend my life."

"And meanwhile I was beginning to see myself having a limited capacity for doing the same thing over and over. Waaay limited. I had by then, after a lot of years and hard work, mastered the knack of drawing as well as the best in the business, and even with my added trademark specialty of infusing my figures with a particular energy/vitality, I was beginning to have vague, nagging worries that that might be all there was. Oh, there was still room for improvement in my work, I knew, but in much smaller increments, the challenges more internal, more head-of-a-pin personal."

"Still – none of these concerns translated into my actually asking hard questions, such as really reexamining where I was going. I mean c’mon – wasn’t the comic-strip my Grail? My unquestioned Calling? My True Belief? So none of that mounting negativity about it – none of those intimations – could apply to me, right…?"

"…Nonetheless, I immersed myself, struggling to find ways to lay down a reproducible line that permitted more expression, was fresher, freer and more interesting than, say, the standard India-ink, brush-or-penpoint rendering. To that end, I’d begun experimenting with different tools – marking-pens, Wolf-pencils, charcoal and the like, and haunting art supply stores in search of drawing papers with unusual surfaces, a different tooth or texture. The resulting changes in the look of my drawings were mostly salutary, and at least momentarily satisfying, welcomed especially by my friend/client, Harry Volk. But even at the time I sensed that I wasn’t addressing the still-larger issue. It would be awhile before I understood why I was so reluctant to look it in the eye, that to do so would mean questioning the entire direction I’d pursued since long before my arrival in New York."

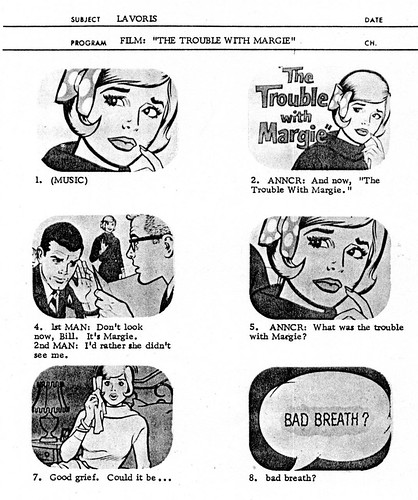

"I’d made several more passes at creating a syndicated comic-strip, each separated by months and my busy advertising illustration schedule. I approached each with progressively less enthusiasm but, because of the changes in my rendering technique, each one had a marginally better ‘look.’ One was about an adventurous space-and-rocket-scientist. I followed that with a strip about a crusading newspaperman. Both were rejected by the major syndicates – and I was in a way relieved. My final attempt, which I pretty much walked through, had a college setting, its protagonist a cutting-edge – and edgy – physicist/professor. I never got as far as trying to sell it."

"It was truth-time."

"Among the many realities-not-faced were personal readings gradually accumulated, about the essential nature of this profession I’d striven for since my teens. About what it did to its practitioners, the comic-strip artists I’d come to know who were successful in the business: Stan Drake, Leonard Starr, Johnny Prentice, Dan Barry, and others. Perceptions, and conclusions drawn that I’d either discounted or otherwise chosen to ignore. Namely, that in watching, and working alongside these guys, I had almost from the beginning seen some very real darksides to their for-that-era high-paying game.

First, I had gotten the sense that all of them were in this velvet-lined trap, profoundly bored by their work, but earning so much that walking away from it was off the table. Though none actually said so (to me, anyway), it seemed that were it not for the mortgages, toys and lifestyles they’d grown used to, most of them would abandon these endless grinds in a New York minute. For the story-strip guys especially, ‘endless’ was the keyword; they were never finished with a job, never experienced closure. One ‘story’ morphed into another, on and on, with no break. I suppose the gag-a-day strip guys had it a little better – but not by much."

"Along with these fellows’ lack of job-satisfaction were what I saw as resultant, very similar compulsive, compensatory behavior-patterns – usually in the form of booze and/or women and/or conspicuous consumption, or general neuroses. I recall commenting at various times that most of them seemed to be sitting at their drawing-boards, ankle-deep in pools of their own blood."

"Now, I realize that these observations had been made through my own, not-necessarily-universal filters, projecting myself, with my own limitations and hangups, onto their situations. And certainly chief among these was what I think of as my Jewish Prince mindset. My assumption, perhaps unreal but mine nonetheless, that I was entitled to enjoy what I did for a living. I mean, it was supposed to be pleasurable, right? Still another side of my slow dawning that not everyone is me. Like ignoring for so long the fact that for the average person, enjoying one’s work is a largely alien concept. Again, I thank my parents for instilling in me my unwavering though clearly romantic belief in that ‘divine right.’ It’s one more gift that has shaped my life and my approach to virtually all of my work: if it ain’t fun, to hell with it."

"That I’ve been able to hang onto that concept, to live it for all but a tiny fraction of my productive years, and, incidentally, to be well-paid for it, is but further evidence of my extraordinary good luck."

"Anyway, while the prospect of actually doing one of these comic-strips had gradually become less and less attractive, I continued to resist admitting it to myself, or questioning it at all. Further, I remained in denial of my need for fresh challenges."

"All this and more had been piling up inside my head, and I’d been doing my best to pretend it wasn’t there. I mean, we’re not exactly talking unique behavior here. And then, one day it came together. Unable to avoid it anymore, I finally, abruptly saw it."

"I didn’t care anymore about becoming Milton Caniff. More than that, I actively no longer wanted to be him."

"I finally knew what I’d known for a long time. That the very idea of spending my entire life working with the same-size sheets of drawing paper, and the same tools, over and over and over, with never a sense of finishing something and starting anew, would cause me, bluntly put, to go out of my fucking mind."

"Okay. But what else was I going to do? What profession was I going to pursue?"

"The good news came unexpectedly, if not somewhat predictably, within a few days. Several years earlier, I’d become fascinated, on a totally amateur level, with making home movies, shooting prodigious amounts of 8mm. film footage of my daughters, of Holly’s and my wedding trip to Europe, and of friends at social functions. The part that had really grabbed me, though, was the editing process. I found myself eagerly cutting and splicing until far into the night, then staring bleary-eyed into the tiny screen as I’d wind and rewind past this or that edit, astonished at the result. I had discovered a phenomenon known well to people who worked in the medium, wherein two pieces of film having been cut together, can often add up to something greater than its parts. Sometimes exponentially so. The creative possibilities were genuinely intriguing."

"For me, contrasting with my childhood, ever-the-outsider view of Hollywood, and maybe because all of the above had conspired to make the stars and filmmakers of that period seem less godlike, the possibility of my somehow getting over that wall had begun to feel like a serious maybe, something to which I just might aspire. It was an exciting, though still very unlikely prospect, but hey – why not…?"

* Many thanks to Tom Sawyer for sharing these fascinating excerpts from his memoirs with us this week, as well as providing such a wealth of fabulous artwork for our enjoyment.

Jim Amash conducted an excellent and very thorough interview with Tom Sawyer in Alter Ego #77, which is still available from the publisher.

All of this week's content is Copyright © 2008 by Tom Sawyer Productions, Inc.

My Tom Sawyer Flickr set.

this is great stuff,leif...will tom be publishing his memoirs?....again,looking at these samples, it obvious neal adams was greatly influenced by tom...

ReplyDeleteLeif, this is the kind of candor and tough, probing analysis that you rarely see in this field, especially from an insider such as Tom. Thank you for posting this. There are a lot of tough trade offs in drawing a strip, as in other demanding professions. I can see Tom's point about the way these commitments leave you with no life, and I would probably make the same choice to escape such an endless endurance contest. On the other hand, whatever toll it took at the time, at the end of your career it must be mighty satisfying to look back on all that work and have that accomplishment behind you. Leonard Starr can look over his shoulder at thousands of beautiful drawings and lovely words and say, "I did that."

ReplyDeleteWow.

ReplyDeleteI can't tell you how much Tom's experience here mirrors my own.

It took 20 years of tryin to break into comics to realize I didn't want to draw comics for a living.

But I loved the artform so much that I wanted to do it on my terms.

And like Tom I get a lot of satisfaction out of shooting and editing film. My day job as a cinematic director keeps my interest if only to break up the moments that I'm not doing comic work.

Crazy...it's always nice to know that you're not the only one with hang-ups like this.

=s=

Thanks so much for this story. I was particularly interested in reading about the person behind clip art. It never occurred to me that there were real artists making it.

ReplyDeleteLove Tom's attitude.