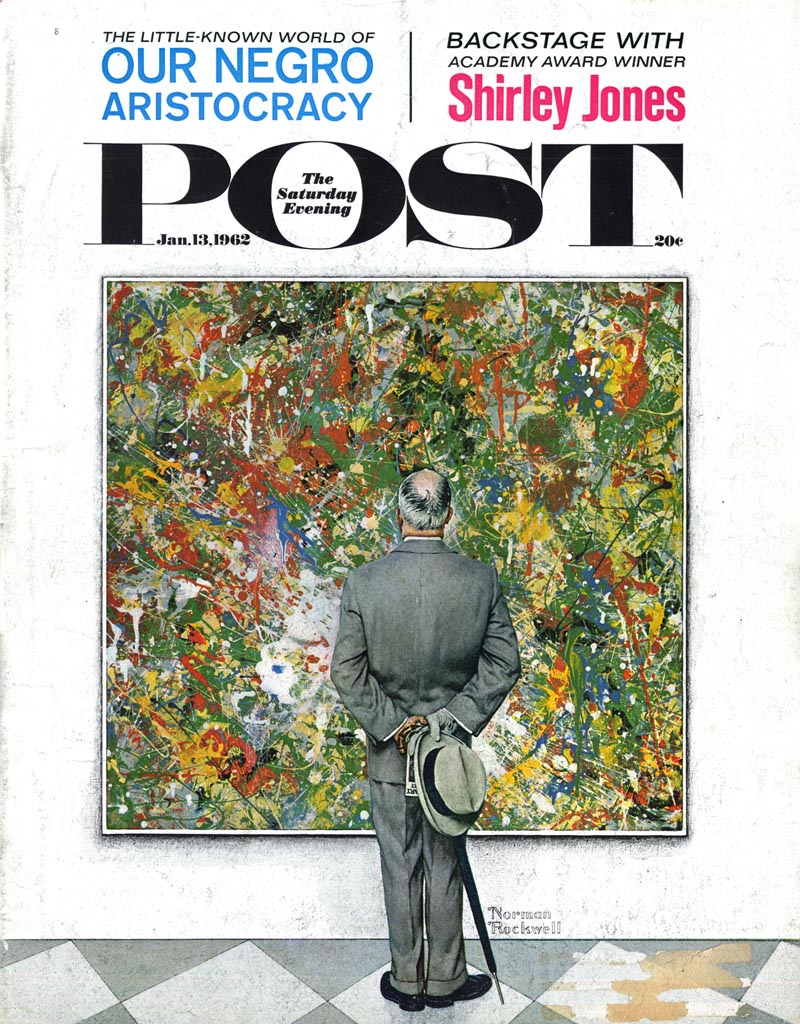

Sounds rather like the thinking of the traditionalist, Doesn't it? But, Weaver continues, "Mine was no longer the era of Norman Rockwell, where everything was easy, obvious, and on the surface.The kinds of stories I illustrated back in those days were rather complicated. I had to find ways to draw and paint that would match the abstract complexities of the writing. Magazines like Psychology Today were publishing articles about complex ideas; they needed conceptual artwork."

"I don't even remember ever reading anything in the Saturday Evening Post - I'd just look at the pictures - but I doubt the articles were very taxing on the brain. In their prime were the Cooper Studio people, the Joe Bowlers and the Coby Whitmores and the Jon Whitcombs. I remember liking Al Parker more than the others, although he certainly did that type of cutesy stuff. It was the ponytail period in American culture."

In the 1959 New York Art Director's Annual, Austin Briggs wrote this message to his fellow graphic arts professionals:

"It is common to blame the low visual quality of most advertising on either clients or the public, but the art director must ultimately accept the responsibility for the job which passes his desk. The art directors who are represented in this book are esthetically and commercially successful because they gave their artists freedom and managed to work in freedom themselves."

"They were willing to experiment and take risks."

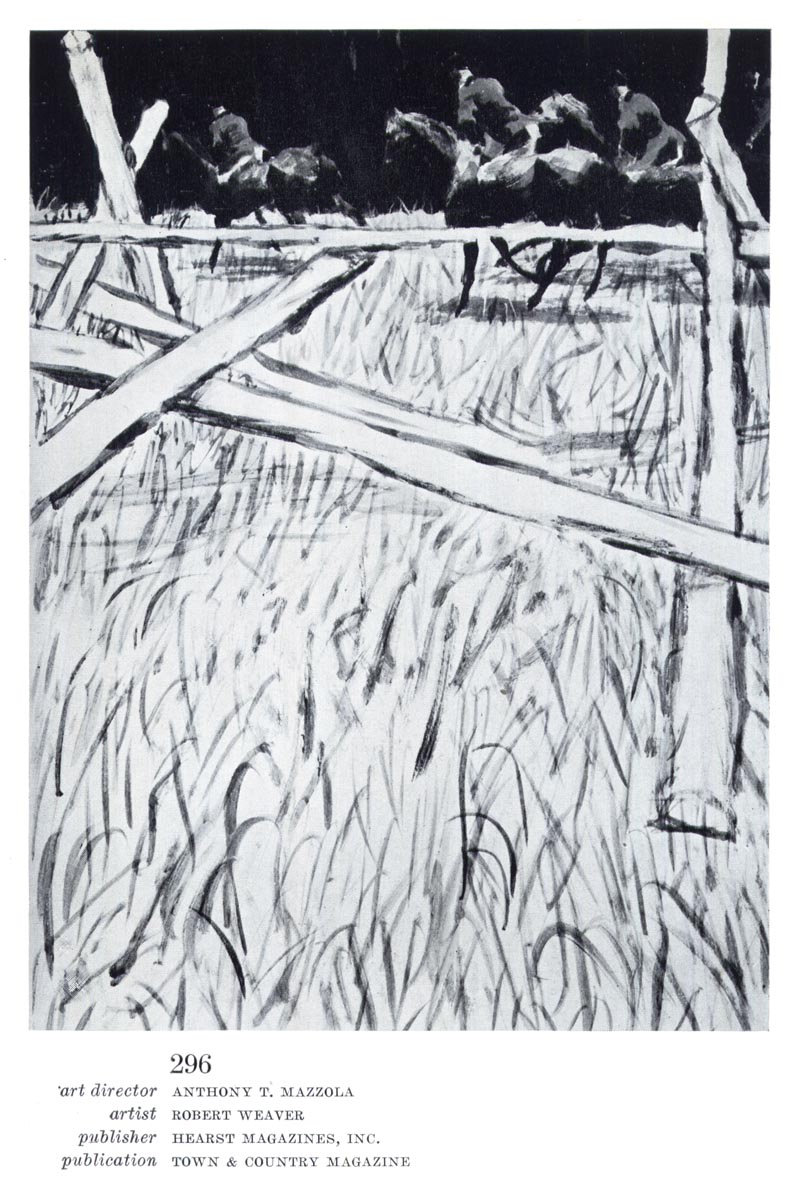

Robert Weaver's earliest accepted submission (below) to the NYAD Annual is included in the section directly behind Brigg's message.

The discussion this week around Weaver's art and philosophy have been passionate and polarized. His remarks have infuriated some readers and his work has been heavily criticized by others. Credit has been given almost grudgingly - and in a qualified manner. Weaver may be adored by one camp of artists - but he is nearly dismissed by another.

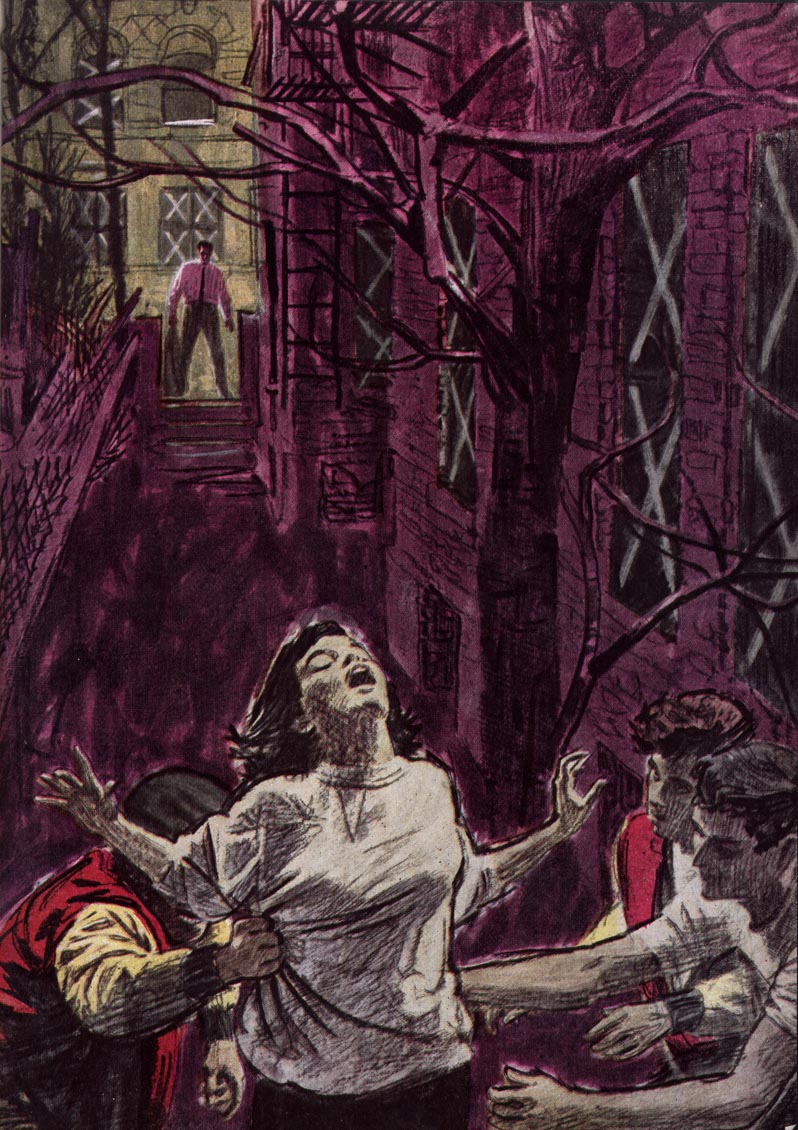

But dismiss him as you might as an elitist, a no-talent, a contributor to the "uglification of a great period in American art," as one person wrote, by the time Weaver was showcased in the September 1959 issue of American Artist, his influence on the look of then-contemporary illustration was becoming pronounced. Even established illustrators (including some of the industry's hottest young talents) were being influenced and attempting to incorporate a "Weaver look" in their work.

Consider the following examples (and I could easily show you many more):

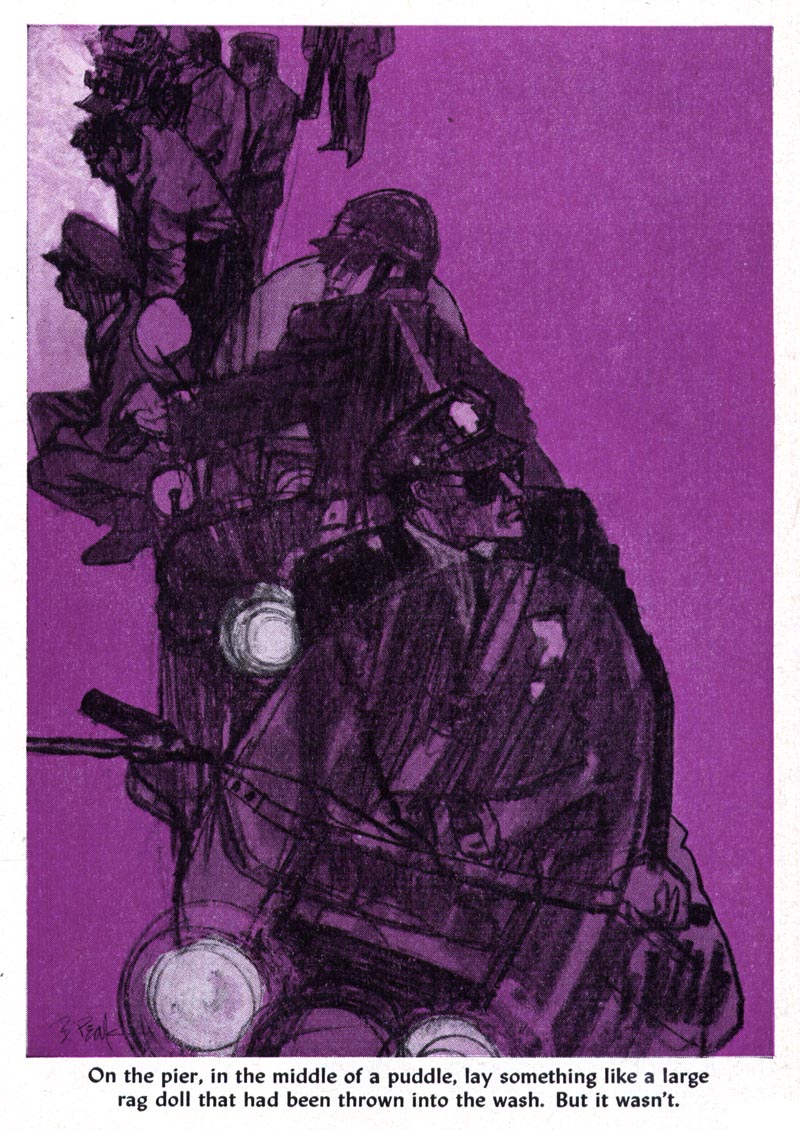

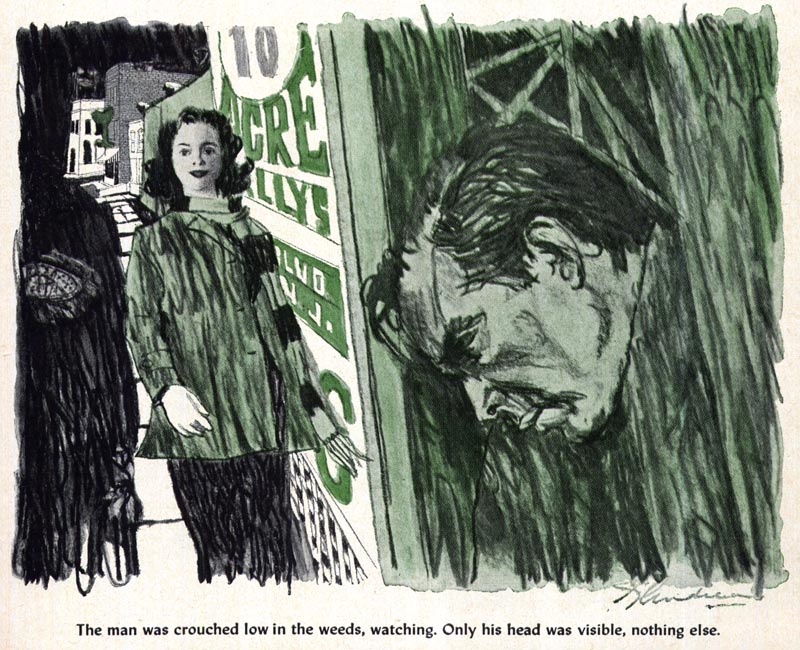

Bob Peak, 1962.

Bernie Fuchs, 1962.

Bernie D'Andrea, 1962.

Mitchell Hooks, 1962.

Of course I'm not saying Weaver was the only avant-garde reshaping the look of illustration. Some others who were rising to prominence around the same time:

Phil Hays

Tom Allen

Jack Potter

Cliff Condak.

There were, of course, many others.

Clever, open-minded illustrators willing to grow and experiment took what they saw as intriguing or appealing from this younger set and incorporated it into their own ever-evolving styles.

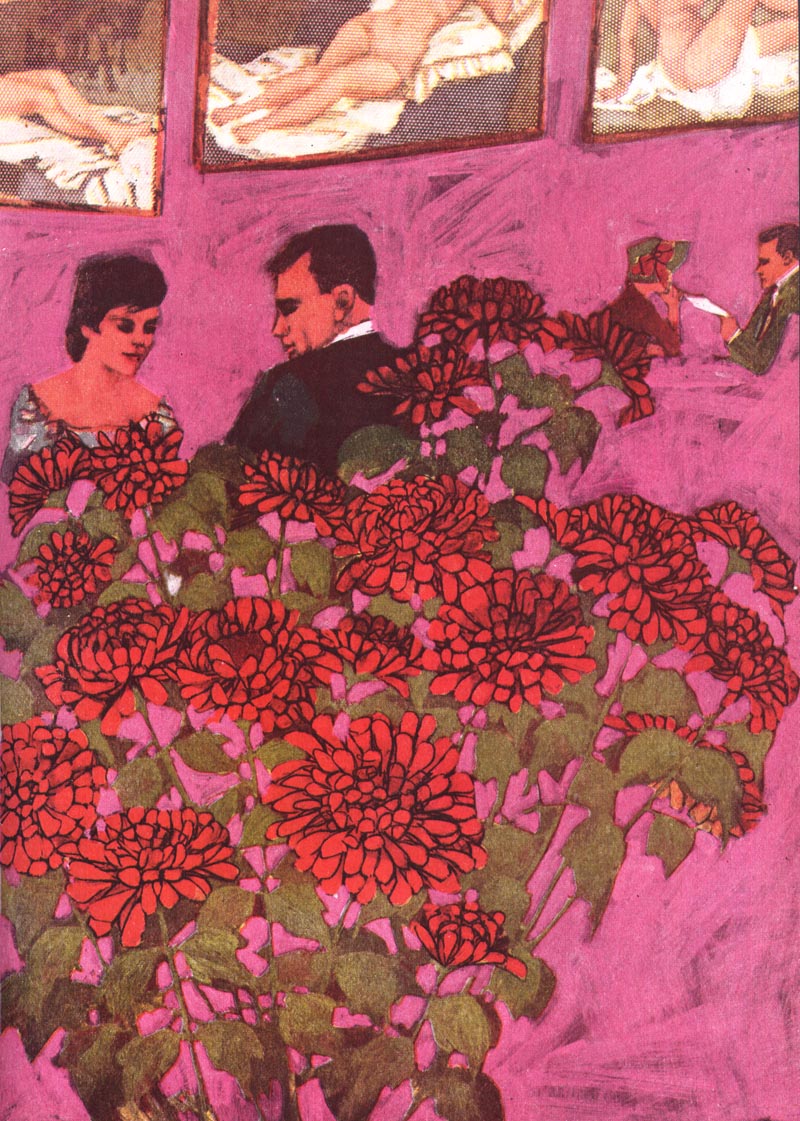

Al Parker, 1964.

The real genius of someone like Al Parker is that he understood the need for personal growth - but also the requirements of the marketplace.

The hurdle avante-garde illustrators face is the audience, the client and in many cases the graphic arts community itself is resistant to change. One commenter this week wrote, "was the public really looking for a wave of innovative "progressive" illustration approaches to seduce them into reading the magazines, or was it driven more by the Art/Creative Directors and illustrators like Weaver... illustrators that hated illustration as it was?"

According to Austin Briggs, what the public was looking for should not be the guiding principle of the graphic arts community. Briggs said its imperative that the art director be willing to take risks and experiment, to seek out and nurture the new and unusual - in spite of what the public may be comfortable with. It is to the benefit of the truly creative graphic arts professional to keep an open mind when confronted with the results of that risk-taking.

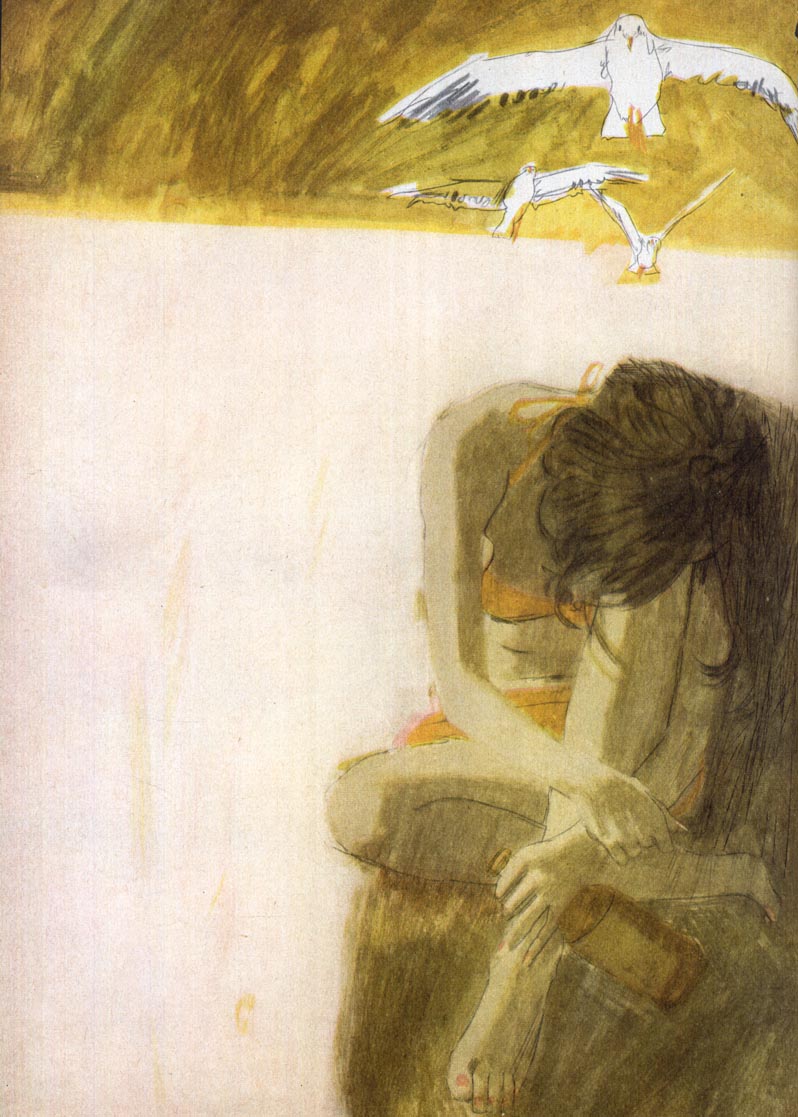

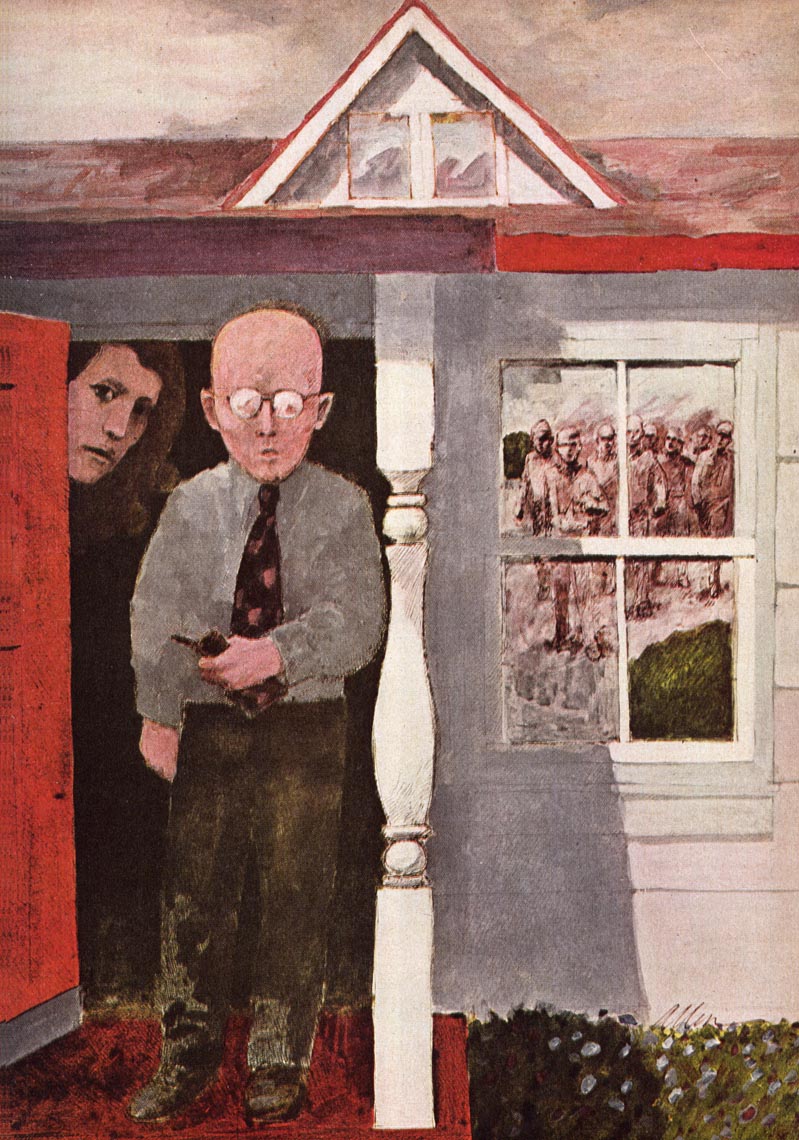

Robert Weaver, 1957.

Because it is the truly enlightened illustrator who sees the potential in what most others might dismiss - and considers how it might be incorporated into his own journey of artistic growth.

Austin Briggs, 1965.

* My Robert Weaver Flickr set.

Thank you for your post. I appreciate someone answering all of the left handed compliments and bashing that has been going on toward Weaver and his work.

ReplyDeleteBeyond his skills, which were tremendous, his willingness to focus on content over style and subject matter over technique are the ways in which he had the biggest impact on illustrators. He brought a serious view to serious issues and humanized illustration.

Best,

Bill

Bill; I've really enjoyed reading your well-reasoned and diplomatic defense of Robert Weaver this week - you were really out numbered by the opposing side on this one and you held it together like a trooper. Congratulations. :^)

ReplyDeleteI wasn't even going to get into the more complex issue of weaver's influence beyond mere style - that alone is more important than many here are willing to admit. Beyond that, as i said at the beginning of this series of posts, I believe he had a profound philosophical influence on a whole segment of illustrators. Looking around the Internet its plainly evident that he is a heroic figure to those artists I described as being sort of hybrid fine artist/illustrators - someone like Sue Coe, for instance.

You asked in an earlier post why I don't particularly like Weaver's work and I can only say that "that's just the way art is!" - I can appreciate almost any art but stuff you more typically see here appeals to me much more than what Weaver does. "To each his own." - but I very much value what Robert Weaver (and others) contributed to the evolution of illustration at a particularly crucial turning point in the history of the business.

The avaunt styling of Peak, Fuchs, and others somehow don't have the stigma of the sixties and are just as fresh as a lot of modern art done in the forties seem today.

ReplyDeleteTo me it's all in the execution. Peter Max had a style similar to Heinz Edelmann, the designer for the movie, "Yellow Submarine". So much so that people confuse Max with the film. If you look at a body of work by both artists it's plain to see Edelmann was clearly more gifted.

This is one of my favorite Normann Rockwell pictures!

ReplyDeleteN.R. was perfect in anything - the way he so painstakingly depicted this grand abstract painting here, with the puzzled observator in front of it, wow; just wow!

All these daring illustration examples showed on this post look great to me. Would they not have happened without "pioneering" Weaver, as somewhat suggested here?

Or in other words: Without Weaver's appearance on the scene; would all these brilliant illustrators not have budged and unerringly stuck to their accustomed ways?

Guess things were just "in the air". And Weaver surely had his antenna.

Rich;

ReplyDeleteTheoretically, who knows? - anything is possible I suppose, but as David pointed out yesterday in his anecdote about Weaver scaring off a young, advice-seeking Bernie Fuchs, it was Weaver who was there at that moment in history, clearly being admired enough by a young Bernie Fuchs to be sought out for advice.

What I hoped to accomplish here this week is to track an evolution is style development within the industry. From my research I conclude that Weaver was the linchpin in this particular "rough drawing", "sketch-on-sight" trend. I'm sure he wasn't the only influence, but from cross-referencing the work of various illustrators in various magazines from a certain time period, and then comparing that with what was being selected for displayed in the AD annuals during that same period, and then adding to that the fact that Weaver was selected from among his contemporaries to be the focus of a major feature article/interview in American Artist in that same time period as well... well, 2+2+2=6.

A great ending to a great week, Leif. (Perhaps my opinion is reinforced by the fact that I share your views of Weaver's strengths and weaknesses). I particularly liked your thoughtful selection of work by other illustrators.

ReplyDeleteAs for Weaver's "rough line" approach, Murray Tinkelman traces it back to a groundbreaking series of advertisements that Ben Shahn illustrated for CBS. (As you have noted in previous posts, David Stone Martin did some illustrations for the same series). But Weaver certainly developed it in some of his splendid drawings you have included today.

There's a small riddle for art lovers incorporated in the pink Phil Hay example up there:

ReplyDeletethe cut off nudes on the wall.

The one in the middle is the most obvious; nude Maja by Goya. The one on the right is by Renoir. Only the left one I fail to decipher...

Manet's Olympia?

ReplyDeleteOK, so Weaver gets the credit for helping to hasten the decline in the classic period of American illustration. But in the long run how useful was that?

ReplyDeleteBy promoting this so called 'intellectual' approach to illustration he helped set off a chain of events that ultimately stripped the profession of all its glamor and craftsmanship to a point where a doodle becomes a valid expression of an idea.

That's fine if you like that sort of thing but when you see an old copy of the SEP its the work of Parker Hooks Bowler et al that make it something special and that's what Weaver helped take away. Is that progress?

Right on, Chad. I'm just glad we didn't have to deal with Weaver or his theories out here. Here we respected disciplined values in illustration....design, composition, draftsmanship, originality....the traditional elements that define various artists and their work. There are certainly enough challenges in pursuing the traditional goals to last a lifetime.

ReplyDeleteThe fact is, the classic period in illustration was over. Charlie and a few others who were as exceptionally talented (and, frankly, fortunate to be in the right place at the right time) were able to continue with only minor adaptation to style. But for the vast, vast majority of classic illustrators the business, as they had come to expect it, imploded. Those old copies of the SEP you speak of became terrifically slim and almost entirely devoid of illustrations after 1960. Compared to the early-to-mid-'50s issues, the amount of work for commercial artists in what had been a primary revenue stream (magazine advertising and story illustration) was diminished by probably 95% after 1960.

ReplyDeleteSame with every other magazine. And worse: Colliers, gone. American magazine, gone. Woman's Home Companion, gone. Look and Life, almost always filled with photography only by the mid-50s.

Proof of the profound impact of this decline: Cooper Studio, gone.

Because of Weaver (and his contemporaries) other smart, open-minded illustrators like Fuchs, Peak, Briggs and Parker saw something intriguing that they could incorporate and refine and make palatable for broader public consumption in their own work. Subsequently others, like Charlie, saw something in Fuchs et al that they could incorporate in their own styles.

Weaver and his fellow 'avant-gardists' (and the enlightened ADs who still wanted to use illustration, god bless 'em) deserve the credit for showing the traditionalist illustrators that there was a way to make illustration a viable, desirable alternative to photography.

How is that not a positive?

LEIF....Thanks for a provocative and eye-opening week or two. I've learned a lot. I won't yield a single opinion, though, on my emphasis being on the traditional values of illustration as practiced in the 'old days'.

ReplyDeleteAnd by the way, what brought down the magazines and the other venues for artists and illustrators had nothing to do with the style, quality, or content of the magazines. It was totally a function of a technical and digital revolution in media. People stopped reading to watch TV and all the entertainment provided. Ad budgets and print budgets were shoveled into the 'new' media. The print media was starved out. Later on the same trend with computers and all the modern gadgets so popular today.

This comment has been removed by the author.

ReplyDeleteI'm late to the party today, and I can't really come up with an intelligent argument against Charlie Allen or Chad Sterling comments. They seem to be speaking of the same things that I experienced. Leif, I have to admit that I hadn't really looked at Robert Weaver and the avant-garde movement in the same way as I have this last week. Your input and all the comments, interviews and strong opinions have solidified in my mind, what had been a subtle seduction from my past in my subconscious.

ReplyDeleteAs a young student and beginning illustrator, I was like a kid in a candy store.. being jerked in all the different directions that illustration was going.. just too many approaches to digest. In my first two years of art school, I was taught to first learn the "disciplines" cold, and then we could experiment with a solid foundation under us. But along came illustrators like Weaver, who's academic drawing skills in many of their figures, looked like they were at about the level of most second year illustration students. Of course, the awards in the shows were going to the new wave illustrators.. because it was 'the new look'. Due to the emphasis on unusual compositions and surface effects, rigid academic training became diluted in many art schools, determined by my own experience and other illustrators I have talked to.

I am convinced it was the solid auto industry illustration disciplines and his excellent taste that elevated Bernie Fuchs to his super star status and longevity, after Weaver's popularity faded from the public eye. I'm not dismissing Weaver's attributes, as I admired them at the time, and I still find some of his illustrations inspiring in their compositions and point of view. And, he has his place in illustration history. But, the importance of well honed traditional drawing and painting skills can not be dismissed as simply "old school" or passe. They are as important as the skeleton and muscles are to the human body.

Leif, a sincere thanks for another thought provoking and always informative week.

Tom Watson

Personally, I think some of Weaver's stuff has strong graphic design and would make for a pretty page. More decoration than illustration, though. A decent graphic imagination? Surely. Deep? Hardly. Bright colors, Dirty Colors, rough line, naive silhouettes, flat depth, la de dah.

ReplyDeleteAll the talk of him being innovative or a revolutionary seems a bit like hype to me. Maybe he talked a good game and made himself a lot of friends in the radical milieu or in the schools. But Ben Shahn was way ahead of him in everything he was known for, prior in time and better in quality, and Weaver never caught up.

As well, a look through the advertising and editorial art yearbooks from the early 50s pretty well defeats any claims he has on being a radical anyhow, leaving aside Shahn. Those annuals are filled with innovative work from all different angles. So graphic innovation was clearly in the air, for better or worse.

Look at David Hockney's

Laundrette, 1955 and then look at the Robert Weaver downshot from 1957 you posted. Might as well have been done by the same artist, as far as I can tell. And here's a Ben Shahn from 1939.

So this idea that everything before 1957 was staid and then the Robert Weavers came along to blow away the cobwebs is just a load of malarky. He was a late adopter compared to a real innovator like Shahn. He didn't evolve like Al Parker. And he didn't transcend the style and era like Fuchs did.

Actually this is getting to the root of an 'issue' I've been carrying for years in fact ever since I started looking at classic period illustration.

ReplyDeleteI had seen little bits of Parker Briggs Bowler etc but had never really connected the dots until I picked up some original publications.Wow! now this was great stuff, illustrations full of great drawing design and color, I didnt know anything about the history in those pre-internet days, but I wanted to find out some more.

So one day I'm fortunate.At a garage sale I find a copy of Illustrators 63, some really great work: Whitmore, Bowler, Peak, English, Fuchs even John Gannam. But there's this other stuff, scritchy scratchy drawings, work that looks like its been painted on paper napkins or blotting paper, ugly little cartoon figures, half-completed pictures,some drawings by Briggs that look worse than his Flash Gordon days 20 years earlier.

Well I bought the book, obviously, but I always wondered what kind of collective madness had overcome that once great dream factory to produce this low-level garbage.

And now I know.

It was the rise of Weaver and his school. Who I now see wanted to be 'significant' and 'real' like their idol, Shahn. They say a little knowledge can be a dangerous thing.And they were right.

In the same way intellectualism ultimately killed modern jazz it also did for illustration.

Thanks for solving my mystery,Leif.

I don't even know where to start. The opinions I have read seem really half informed, and give very simplistic reasons for the lack of illustration in magazines or the "death"? of modern jazz.

ReplyDeleteEvery great artist is influenced and "borrows" from those who came before. Ben Shahn was a genius painter and photographer. If he didn't have an influence on a generation, I would be surprised.

I think that for me, a feature on Norman Rockwell on CBS Sunday Morning points out why I prefer Robert Weaver to Rockwell or some of the other illustrators of that era, and the failure of illustration to reflect truth. Rockwell's work does, I think reflect an aspect of the truth. Though he composed and planned out and then projected his images onto canvas and then drew them, altered them and then painted them, he had an astute eye and caught some real truths on canvas. He had real skills of observation, but controlled his pictures from the get go. None of this is bad. I respect and admire his skill.

Weaver on the other hand, though he did shoot reference and even used models at times, was trying to capture something of the life around him and show things that had no been shown. His people seem unposed, and his world has a credibility that is lacking in a lot of other illustration of that time and after. It is the difference, of a Bouguereau and a Degas. However pretty the former is, it lacks the truth of the latter, much the same way that Hitler's watercolors lack the truth of Beckman's drawings or any of the German Expressionists' works.

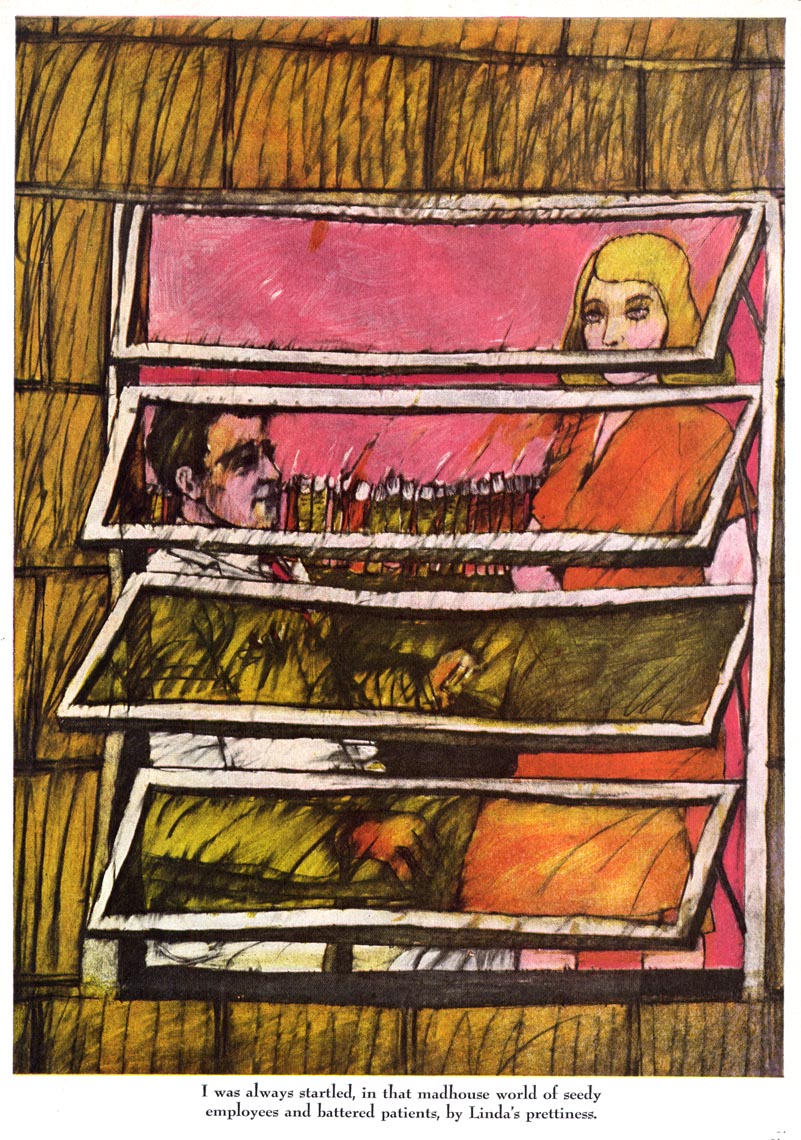

There is a series that Weaver did for Life on the accounts of a former street gang member and his change from gang leader to working in the medical field. One picture show him laying in his bed in a youth camp, looking through the bars of his bed's frame. The drawing has a credibility. After looking at it I realized that the drawing was made a good ten years after the event in the story took place, but it had a truth and credibility to it.

I think that this credibility is the main thing that I value in picture making. Despite technique, despite prettiness, without it, pictures are hollow.

As for Weaver fading. Well, he was working until the mid 80's and then symbolic illustration came into vogue. A lot of illustrators have seen the death of their livelihood over the generations when younger ADs have come along and styles went out of favor. This has nothing to do with an artist's skill or style. It is a thing that happens. I have seen it happen at least three times in the past 25 years due to many, many factors.

Cheers,

Bill

Here's an interesting press notice from 1876:

ReplyDelete"The Rue le Peletier is a road of disasters. After the fire at the Opéra, there is now yet another disaster there. An exhibition has just been opened at Durand-Ruel which allegedly contains paintings. I enter and my horrified eyes behold something terrible. Five or six lunatics, among them a woman, have joined together and exhibited their works. I have seen people rock with laughter in front of these pictures, but my heart bled when I saw them. These would-be artists call themselves revolutionaries, "Impressionists". They take pieces of canvas, colour and brush, daub a few patches of colour on them at random, and sign the whole thing with their name. It is a delusion of the same kind as if the inmates of Bedlam picked up stones from the wayside and imagined they had found diamonds."

This piece could very well have been included in that exhibit. Tom, this looks to me like "academic drawing skills [of] about the level of most second year illustration students."

Charlie, Tom, Kev and most especially Chad; your arguments all sound like the cranky griping of the juries of the French Salon.

Bill; once again, I applaud your well reasoned, well informed and open minded rebuttal.

Hi Leif,

ReplyDeleteyour post has me rolling on the floor with laughter.

The arguments remind me of a scene in the movie, "Thank you For Smoking" where the father and son have a mock argument over what is better, chocolate or vanilla. THe son says that chocolate is the best flavor ever to which the father says that he likes chocolate, he also likes vanilla, but what he really likes is living in a country where you have the freedom to like what you like and have your choice, and that's the great thing about America. The kid says that he isn't convinced and the father says that he isn't trying to convince him, he is trying to convince them, and gestures to an imaginary crowd.

This is how I feel about the art world. It is great that people have the freedom to choose to be influenced by whom they like, whether it be older illustrators, modern art, children's art, or their own inner eye. This is the beauty of the conversation we call art, that we can all choose what we like or don't, and what we want to do with it.

I don't mind being called "cranky" for making a particular argument. Especially when there's no counter-argument to what I've said accompanying that pejorative.

ReplyDeleteI want to commend Bill however, for having the correct opinion on the matter. ;)

" One picture show him laying in his bed in a youth camp, looking through the bars of his bed's frame. The drawing has a credibility. After looking at it I realized that the drawing was made a good ten years after the event in the story took place, but it had a truth and credibility to it."

ReplyDeleteSo in other words he was adept at faking the 'truth' he sought to present. Weaver was at heart a competent stylist who was out-Weavered by many of the real talents that commandeered aspects of his style.As shown on TI.He was a one-trick pony who was able to get away with his shortcomings by using this 'direct' approach.

Actually I like the baseball drawings he did.But I can think of many other artists that could have done a better job.

As for my comments on jazz, if youre not aware, Modern jazz, a once vibrant form ,became so tuneless and esoteric in the 60s that it ceased to have any significant popular audience.If you cant see the parallel.

"I think that this credibility is the main thing that I value in picture making. Despite technique, despite prettiness, without it, pictures are hollow."

If you want that kind of thing, look at the work of Martha Sawyer, featured recently or William A Smith. As far as I know their drawings of WW2 were made DURING WW2, not 10 years later.

That's real credibility.

I'm not much a fan of Weaver's work. I get the sketchyness of it, and enjoy that to a degree - as sketches, but not as a finished work. I'm left as a viewer to fill in too much of what's missing, so I can't appreciate what he brings to the art. As for "visual jounalism" I don't see that at all. There's not much there visually or journalistically. There's an image from the Chicago Crane series showing what looks to be a large orange beach ball being made on a floor where someone spilled a tub of blue ink. Was that what happened? So much for his reporting skills.

ReplyDeleteWeaver's modern style has been playing the same tune for some 60 years now. His work looks as anachronistic to me as Wyeth's does to others. It's time for a new one, or for me, something older that's new again.

Leif's quote: "Charlie, Tom, Kev and most especially Chad; your arguments all sound like the cranky griping of the juries of the French Salon".

ReplyDeleteI think we are all expressing our point of view, preference and experiences, which is constructive and insightful on both sides of the discussion. I prefer to call it discussion, as it is less inflammatory than the word "arguments". I looked up synonyms for "cranky" and "griping", and I'm puzzled at your choice of words. I have no irritability, anger or even frustration at other opinions that differ from mine, when it comes to illustration.. even when I'm told bluntly that I am wrong. I have heard almost all these points of view in debates I have witnessed or participated in, going back to 1958. It started with the fine arts students telling the illustration students we were "gutless sell outs", and we were "prostituting our talent". They claimed that "the real artist painted for himself, not for the masses that didn't understand the importance of the true meaning of being an artist". They denounced and even ridiculed the importance of academic training as being an "unimportant restriction left over form outdated academics". In their view, art was all about your "feelings", and that was too important to waste time learning disciplines from the past. The fine art students and even some of the illustration students considered Norman Rockwell's illos as the poster child of the worst attributes of repulsive unsophisticated American illustration. They thought Rockwell illos were sacrilege to the art world, and they were furious that his illos were loved by the public. Anything Picasso did was the ultimate of cool. And, the new wave of Abstract Expressionists were their heros. They were convinced that realistic fine art and illustration was disappearing forever, and it was the subjective innovator that would be the future. Sound familiar? How "open minded" is that?

So, I've had a long time to reflect and watch what came in, what went out and what stayed. And, I have no regrets for being a believer in a strong academic foundation for the illustrator and fine artist alike.

As for the French Impressionists rejection by the juries of the French salon, that is another popular point that is often brought up in defending so called "innovative directions". The French Impressionist were all grounded early in their art training, in rigid academic standards. So, most of them knew how to draw and paint three dimensional form very well. I think to compare the "cranky gripings of the French salon jurors", to those of us with traditional backgrounds, and/or disagreements expressed toward Ben Shawn, Weaver and that group, shouldn't be confused with the French salon jurors back in the Victorian era. Looking at the past through the prism of today, often clouds and distorts the thinking of the past. We don't really understand their perspective at that time in history. We can read their quotes, etc. and draw our own conclusions.. which varies, depending on our own experiences, knowledge and personal preferences.

Leif, I don't believe you wanted to encourage only agreeable and complimentary comments, as self gratifying as they might be. The important thing, in my opinion, is that we can all discuss our viewpoints and learn something in the process, without verbally sniping at an apposing viewpoint, even if we think it's dead wrong. And, that is the real benefit of yours, David Apatoff and other blogs.

Tom Watson

"Mine was no longer the era of Norman Rockwell, where everything was easy, obvious, and on the surface."

ReplyDeleteThis quote sums up the problem with Weaver and his acolytes: pompous, arrogant, self-righteous, condescending. The Depression, World War II, etc. were "easy, obvious, and on the surface?" Speaks for itself.

You nailed it Steve. Excellent point. Bravo!

ReplyDeleteTom Watson

Well, I've had to step away while I plowed through a ton of freelance, but I'm happy to see you've been carrying on and on without me.

ReplyDeleteI'll just dive in one at a time then...

Kev;

Here is your counter-argument:

Insisting that Weaver doesn't deserve any credit for shaking up the illustration business in the late '50s because Ben Shahn "Shahn was way ahead of him in everything he was known for, prior in time and better in quality," is like dismissing the Rolling Stones, Led Zepplin and Eric Clapton because Robert Johnson was doing The Blues first.

Weaver credited Shahn with being his inspiration, by the way, just as the early rock stars credited Johnson. But they still got to be the rock stars.

Chad; You're off base comparing Weaver to tuneless modern jazz. He more accurately could be compared to Punk Rock.

ReplyDeleteLike Weaver, Punk was "significant and real" to a great many young people while mainstream pop/rock had grown tired and predictable.

Punk was about rebellion and so was Weaver. Its what young people ought to do. Others (perhaps with more - or different - talent) figure out how to take that raw energy and refine it into something more palatable to a mainstream audience. I think Briggs' later work is beautiful and your comment about it is... uncharitable - but of course if we've learned nothing else here this week its that beauty is in the eye of the beholder.

Charlie; That was my point - the dramatic shift in technology ( fast film, tv ) made literal illustration redundant. It opened the door for stylized, conceptual artwork - and caused art directors to seek out artist who could deliver "something different" - their innovations trickled down to more mainstream illustrators like yourself in the form of technique adaptations ( the rough sketchy style, the rainstorm effect ).

ReplyDeleteTom; you clearly missed the humour in my comparing you to the salon juries. Read en masse, yours, Kev's, Charlie's and especially Chad Sterling's comments are like a relentless barrage of scorn heaped on Weaver. Seriously, go back and read them one after another - its like a pile-on. Hilarious! It so reminded me of what I'd read about the rejection of the Impressionist by the patrons and art critics of the Salon. Seems Bill could see what I was getting at, hence his "rolling on the floor with laughter" while you were busy consulting a thesaurus.

ReplyDeleteNo need - "cranky" and "griping" were the words I chose because they were the most appropriate to describe the impression I have of you four based on what I read here.

Sorry to say, Steven K; not only did you not nail it, you hit your thumb with the hammer. Mention Rockwell to the average layman and if they know of him at all they'll think of small town America and Thanksgiving turkey, not the War or the Depression or "etc." - whatever that was meant to suggest.

ReplyDeleteThat's what Weaver was talking about - he was using Rockwell as a sort of symbol of the state of illustration during those days. For all its exceptional craft, nearly all illustration was simplistic in terms of interpretive content: take a passage from the story and represent it visually.

Read a little deeper into that Weaver quote you'll see that he was saying that illustration assignments were becoming more 'conceptual' during his period - requiring a different way of visually interpreting the related text.

I'm not sure why this matter-of-fact statement so offended you that you felt you had to characterize Weaver and anyone who admires him as "pompous, arrogant, self-righteous, condescending."

(Which would include me and Bill Koeb, btw, thanks a lot!)

* And Tom, when you applaud that kind of "verbal sniping" as you put it, with a "Bravo!", how can I take your claim seriously that you value the so-called "discussing and learning" of opposing viewpoints that is (supposedly) going on here?

Again, this is just a pile-on and again, you're amusing me.

No, Leif, I didn't hit my thumb with the hammer - Weaver hit his. So have you. Those are Weaver's words, not mine. I did read the rest of it, and it just gets worse. The fact that he had to use Rockwell "as a sort of symbol of the state of illustration during those days" is merely an indication of Weaver's arrogance and intellectual laziness. Much like the Modern Jazz "artistes" who dismissed Louis Armstrong and his generation so they could "save Jazz." Weaver and company had about the same effect - if nothing else, they took all the fun out of illustration. And since you brought him up, what would the "average layman" remember Weaver for?

ReplyDeleteNothing.

Would that be because Weaver did not consider the average layman "worthy" of his "more conceptual" illustrations?

Weaver and his acolytes casually dismissed generations of illustrators, going so far as to tell many of them they weren't "real illustrators" because they didn't work for the "right" magazines and demonstrate "high concepts." Because of course, everyone knows that thinking ("concept") is so much more important that doing("craft," or, as I call it, "execution.")Bear in mind that under "execution" I consider things like acting, drama, staging, action, expression - everything that makes a picture worth looking at. None of which Weaver exhibits. Bob Heindel illustrated Psychology Today articles as if they were fiction - dramatic and evocative. Weaver illustrates fiction as if it were an article in Psychology Today - turgid and ponderous.

But it is Weaver's words I take issue with: pompous, judgmental, arrogant, dismissive, elitist and above all self-serving and self-righteous. Like any "Modern" in art or music, sought to justify his own shortcomings by repeatedly undermining the legitimacy of others' work. In no position to challenge their craft or execution, he resorted to trivializing their "concepts." And just when did "taking a passage from the story and representing it visually" become a bad thing? Oh, that's right - when Robert Weaver said so. Well, if it was so easy - why couldn't he do it?

Tell you what - hang a Weaver between a Rockwell and a Cornwell, and let's see what happens. Or, if it makes you more comfortable, I'm fine if you hang it between a McGinnis and a Frazetta, or between a Norman Saunders and a Reynold Brown. It doesn't stand a chance in any case.

And as to why I am so angry, I suggest you talk to some of the illustrators from that era and see how they were treated when Weaver and company and their attitudes ruled the SI and the illustration establishment.

Weaver and company were the death of functional drawing in editorial magazine illustration for a generation - and come to think of it, the fun too.

Leif, I've written enough for a novel at this point, so I won't go back over it again. I don't disagree with you on all your points about Weaver, but I really thought that Stephen K. got to the heart of Weaver's tacky remark about Rockwell. I think Weaver had a bad attitude, and in spite of his talent, he will always be a flash in the pan.. with a big mouth. Weaver was like the "leisure suite" of the 70s'... popular at first, but didn't last long.

ReplyDeleteMy comments are not meant to convince anyone, just my point of view. And Leif, I don't think disagreeing with your point of view constitutes deliberately "piling on Weaver", nor do I think it reflects on you negatively. It's simply a contrasting opinion.

Peace,

Tom Watson

This comment has been removed by the author.

ReplyDeleteJust one question. How can you say that Robert Weaver was a "flash in the pan" when his career lasted for over thirty years, he was a monumental influence on several generations of illustrators to follow, is well respected by the top writers and critics of illustration, not to mention designers and art directors, and, drew extremely well.

ReplyDeleteHis work was the way it was because of choices he made based on his point of view about what illustration was, not because of a lack of skill.

Anyhow, I'm done. I appreciate the conflicting views, and it was interesting to read what others think.

Regards,

Bill

Bill, I think Steven K's. comments were quite eloquently on this issue, and all I can add is that by 1972, (perhaps even before), Weaver either did not submit, or was not selected into the New York Society of Illustrators Annual Show. All the hot illustrators like Fuchs, English, Peak, etc., were still going strong with more plumb assignments than they often were able to commit to, due to their heavy work schedule. Weaver's influence was primarily because of his maverick attitude and defying the established standards of draftsmanship and craftsmanship. That was appealing to young up and coming illustrators and designers. He conveyed that the intellect of an illustration was the most important factor. So, why should students think they should learn academic skills, which is hard work. That can be very influential, as were the abstract expressionist painters on fine arts, during the mid century. It discouraged solid draftsmanship as being out of step with future art. But, as all fads, it finally died down and the academics began to come back to the art scene.. and the art schools.

ReplyDeleteBill, all I can express is what I experienced during those times, what I read and what my illustrator and fine art friends experienced and expressed in our discussions. You sound like a level headed guy, and I appreciate that. And, I too enjoy our discussions on TI.

Tom Watson

Leif,

ReplyDeleteFirstly let me thank you for your blog. No animosity here. Just purely enjoy it.

However, you seem a bit cranky on this topic. ;)

On your counter argument: Is Weaver known because he was a rock star? Because he was influential? Or because he was either great or innovative?

I don't care about "rock stars" so let's skip that. And we've already gone over the innovative part. (I'd hardly place the distance between Shahn and Weaver as akin to Robert Johnson and Led Zeppelin. More like Shahn's Rolling Stones to Weaver's Sex Pistols...)

And I certainly don't care about what is encouraged in "academia" as "good" art... and thus don't care how influential he was. (Look how influential Manga is. Should I care about Manga?)

So you haven't given me an argument, you've given me bandwagon-ism disguised as an argument. And then you've heaped a bit of ridicule on top just in case the bandwagonism didn't take.

To wit: If I like Fuchs and Briggs, saying I'm just a rejectionist like the French juries encountering impressionism for the first time is a kind of silly argument, wouldn't you agree? I'm more like someone who appreciated Van Gogh and Vuillard, but thinks Bonnard and Denis are trying to sneak in the museum door hiding under their coattails.

kev;

ReplyDeleteThanks for the complimentary remarks about Today's Inspiration. You're right - I AM getting cranky about this topic. Sometimes the barrage of negativism that comes from certain commenters strikes me as narrow minded and needlessly antagonistic, not to mention narrow minded. Did I mention narrow minded? That as well. ;^)

I apologize that you sort of got swept up in that group I was responding to. "Timing is everything", and your first comment arrived in the middle of that group's onslaught.

Anyway, you and I likely won't be able to find a middle ground on the matter because, from your latest comment, we clearly have entirely different perspectives on the merit of McLuhan's assertion about perception being reality.

Should you care that Weaver was, in a sense, a 'rock star' - in my opinion, absolutely. Just as you should absolutely care about the influence of manga on art and popular culture.

Since you say you don't care, what more is there to discuss? Everything I would use as support for my side of the discussion has been dismissed by you with "let's skip it" and "I don't care about..."

If you're going to restrict all the parameters of the discussion (notice the great pains I'm taking to avoid the word "argument"? - my friend Tom Watson taught me that) then, with respect, there really is no point in having the discussion, is there?

Despite that roadblock, I do appreciate your follow-up remarks. :^)

Tom;

ReplyDeleteThe insight and eloquence you bring to your guest authoring here and many of your comments is always appreciated. I've got too much on my plate to continue with this at this time, but to you and Steven K and anyone else who cares to pursue this further, I will happily return to the topic when time allows.

Thanks :^)

Yes, I think we completely disagree on "perception is reality."

ReplyDeleteIf you read the massive History of Art (currently available at Barnes & Noble), illustration is absent. All those towering talents... not a whisper about them. No brangwyn, no cornwell, no Pyle, no Leyendecker, no Wyeth, no rockwell... there's no Fechin either... no draftsmanship or dramatic depiction allowed after 1880, especially if it was commissioned.

The point is obvious: Illustration just wasn't important as art BECAUSE it was commissioned and it was realistic and it was pleasing.

Is that the reality of Art History?

Does that perception equate with your History of Art?

The same question can be put this way: Are you going to rely on the "experts" to tell you that illustration isn't important art, but a pile of sand in a gallery is?

Somebody is certainly trying to create that perception.

Or should I say, someone is trying to keep that perception intact into perpetuity.

That maoist "history of art" is purely based on faddish vitriol against commercial enterprise. So, perception be damned, I'll create my own pantheon, thanks. My own history of art, my own criteria for excellence. I look for quality in art wherever it is found regardless of venue. I don't think any cow is sacred.

The opinion of the masses is an empty sheet. Their "reality" blows with the wind... depending on which knave with the billows is pumping hardest.

My personal aphorism on the matter is "If we don't think for ourselves, there will be no thinking."

Kev;

ReplyDeleteI'm going to presume that was a rhetorical question, because even a cursory perusal of this blog would make it abundantly clear that I've invested rather a lot of time and energy over the last several years into showcasing the accomplishments of the kind of illustrators you admire. I'm going to allow myself the small conceit that I've probably had more success at introducing the work of the illustrators of that last golden age to young graphic artists than anybody since Murray Tinkelman.

You seem like a pretty reasonable guy so I'm going to try to appeal to your sense of reason...

How is plunking yourself down in one camp of denial any better than the other one you describe?

Just as two wrongs don't make a right, two groups w/extreme POVs won't foster a world of open minds.

I think that's what has been so irritating about this whole series of comments from the "School of Weaver" haters. Say what you ( or Tom, or Steven or Chad or Charlie might ) it reads like "payback."

The lovers of traditional or classic illustration who commented and "discussed" on and on in this thread kept coming back to how much they resented the Weaverists ( hey, I'm inventing a whole new classification system here!)

I said right off the bat that I don't have any great love of Weaver's artwork - again, this blog's content is a testament to what I love - but come on, you all aren't able to see that Weaver cause a massive shift in the broad context of how illustration has evolved over the last several decades?

It seems so abundantly clear to me. And its not just specific to style - its something much more important: a shift in mindset - how a category of illustrators see their role in the business.

I maintain that the majority - not certain specific illustrators you might want to name - but the vast majority of commercial artists before Weaver saw themselves primarily a craftspeople first and artists second. They were content to take direction and do good work that entirely suited the needs of their client.

After Weaver a new class emerged: what he describes as the "painter/illustrator". This group feels, like Weaver did, that the client must accept their interpretation of the assignment - their personal vision. Otherwise why would the client choose them specifically and not some other artist?

Weaver recounts doing his first Fortune cover for AD Leo Lionni. He first tried to do what he thought was expected of him: a typical Fortune cover. Lionni rejected this cover - "I don't want a typical Fortune cover, I want a Robert Weaver cover," he told the artist.

Continued...

Continued, from above...

ReplyDeleteYou may not like the "fine arts superior attitude" of the Weaverists, you may feel they lack genuine admirable skills of craft, but they have continued to proliferate and frankly many do highly accomplished, admirable work. They see Weaver as their guiding light - not Ben Shahn, though they certainly admire him.

To those many, many illustrators Weaver is the rock star and Shahn is an interesting footnote, just as Robert Johnson is to young Stones fans. (over tie, as they mature, they may come to appreciate they genius of the original innovator, but that takes years and maturity) Anyway, that's sort of a side bar.

The point is, as Bill Koeb pointed out again and again, Weaver's been a huge inspiration to a vast swath of illustrators (some bad, some good and some great, just as on the other side) for decades. I think that deserves recognition, not name calling and derision and diminishment of accomplishment.

I would rather the traditionalist take the high ground and say, "Fair enough - that IS pretty worthy. Not my cup of tea, but good on you." instead of lowering themselves to the same "nose-in-the-air" attitude they accuse the Weaverists of.

(And that last not directed at you specifically, Kev - but in a more general way at the group as I (yes!) "perceive" it.)

This comment has been removed by the author.

ReplyDeleteIt's very hard to say complimentary things about images you generally find unappealing. Some of Weaver's drawings are energetic with strong compositions and the stylistic effect he had on Parker Peak and Fuchs was quite energising.

ReplyDeleteBut now I have run out of positive comments and await the Robert Fawcett book where I will find a real master at work.

Leif, with all due respect, are you sure Weaver wasn't a relative of yours. ;-).. just kidding. I mean, you sound personally offended and even hurt that some of us just don't see Weaver as the important figure in illustration that you do. Hey, it's okay to not agree. It doesn't mean there is some kind of betrayal or blaspheme toward you, your opinion or the history of illustration. Weaver seemed to be more influential with graphic designers and decorative illustrators than most of the main stream illustrators I knew or was aware of. I haven't really seen Weaver's influence in recent years, but then I haven't seen much illustration in the public eye recently.. seems like it's just about all photography.

ReplyDeleteWeaver was apparently given cart blanche by most of the ADs from the start, and he still bitched and ranted about illustration and how oppressive it was. Why?.. doesn't sound like he was restricted at all, unless we really don't have the whole story.

I was on both sides of the fence.. art directing my own illustration assignments and giving commissions to other illustrators while working for an ad agency. Also, while freelancing for many years, I did illustrations for ADs, CDs, art buyers and corporate heads. Ultimately, we had to answer to the client, who paid the tab. The client might be an advertising manager or even the president of the company, but they knew their product or service, and they didn't give a rat's hind end about illustration fads or elite attitudes. I never knew a client that felt he or she "must accept the illustrator's interpretation", nor did the AD's think the illustrator should be dictating to them, for that matter. They would look at our ideas, but if they didn't understand what we preposed, or thought it wasn't right for them, it didn't fly. Had I insisted that I knew best, and they must accept my interpretation.. I will let you guess what the result would have been. It would have been an insult to them, and I wouldn't blame them.

"Craft" was what made our illustrations professional looking, no matter how loose, impressionistic, or avant-garde we approached them. Our interpretation or innovative input, had to make sense to the client and to the company's targeted audience. Apparently Weaver stuck his nose in the air and insisted that he should be the top dog in the food chain, when it came to his ideas. I think he was a frustrated fine artist, that started receiving praise and awards as an illustrator, and just wasn't willing to dump it all, and become a gallery artist.. exclusively.

As far as "taking the high road", I don't want to risk a nose bleed. Although you might think differently, that's also why I don't stick my "nose-in the-air". ;-)

Tom Watson

Leif,

ReplyDeleteDuring the heyday of the golden age, illustrators were quite free to do as they wished, (especially if they were trained by Pyle or his descendents). Illustration began as "fine art" for the page.

With WWII, (or maybe even earlier, in the depths of the depression), bean counters, advertising, and editorial consolidated power and ended the golden

age of illustration.

I have no doubt you know more about Weaver's legacy than I. I would have thought Briggs, Fuchs, and Peak had more of an impact. I wonder if they credit Weaver as an influence?

Or was he influenced by them too?

In looking at some pre-Weaver advertising annuals circa 1950-52, I see quite a few pieces that are remarkably similar to Weaver's particular style of graphic primitivism and pattern. I don't know how to reconcile that except to say that it is always difficult to establish priority on styles, as successful avant garde artists tend to lead an evolution, rather than a revolution. This is why, to me at least, quality is more important than style. Without quality, style is just an affectation, a method of selling otherwise inferior goods.

David-

ReplyDeleteWhat is the CBS art that Ben Shahn did? Do you have a sample? I'm curious to see it.

I know that Weaver later worked for CBS. He did location drawings at the CBS studios that were published in a notebook. It's something CBS did every year (Eric, Bouche, and Felix Topolski are some of the other artists that did different years).

We can't blame Weaver and the gang for the demise of America's Golden Age of Illustration. We can't give them credit for introducing the world to a new era of arty looking illustration.

ReplyDeleteIf anyone is interested in the facts, television killed the slick magazines. Period. The big circulation magazines were no longer getting the lion's share of consumer advertising budgets. People had other things to do besides sit and leaf through magazines. But there is much more to the story and how it affected the big changes in illustration.

Pick up any magazine from the 1950s and it was loaded with illustration. In the early 50s David Ogilvy began doing survey studies of the advertising market place. One of the many things he discovered was that people believed a photo in an ad more that they did an illustration. That spelled the end of illustration as the prime method of visual presentation in printed advertising.

With that and the general trend of photos dominating more and more of magazine visual content, art directors began pressing for illustrations that did not look photographic. At the same time, a more sophisticated public was very receptive to good design. Art directors like Otto Storch at McCall's were redesigning the look of editorial print. This was really the beginning of a short but Golden Age of Graphic Design. Storch and others like him were sensitive the the big changes in American society as a whole and were encouraging illustration that looked like artwork.

The entire country was changing—not just illustration. Weaver came along at the right time to look like he was more than he really was. Magazines were going down the tubes. Illustration was going down the tubes. And that, folks, was only the beginning. The world is still in the middle of ever faster changes.

Get best quality History Assignment writing Help online by academic writing professionals in UK. Avail accounting assignment help with Top Ph.D. Writers to secure A+ grades. Our assignment helpers will make sure that your assignments are taken as utmost priority. For more services:-

ReplyDeleteAssignment Writing Services UK

Assignment Writing Help UK

UK Assignment Help

Public Relations Assignment Help

Geography Assignment Help