Where better to begin our look at the "New School" than with Coby Whitmore? Whitmore began his career in Chicago at

Haddon Sundblom's studio so his roots are actually in the Old School.

But he came to New York during the early 40's and joined

Jon Whitcomb at the famous

Cooper Studio - where the two men's work would come to epitomize the New School look.

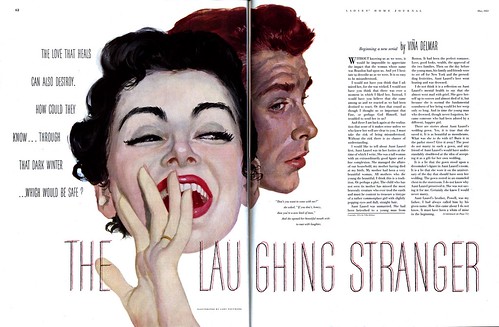

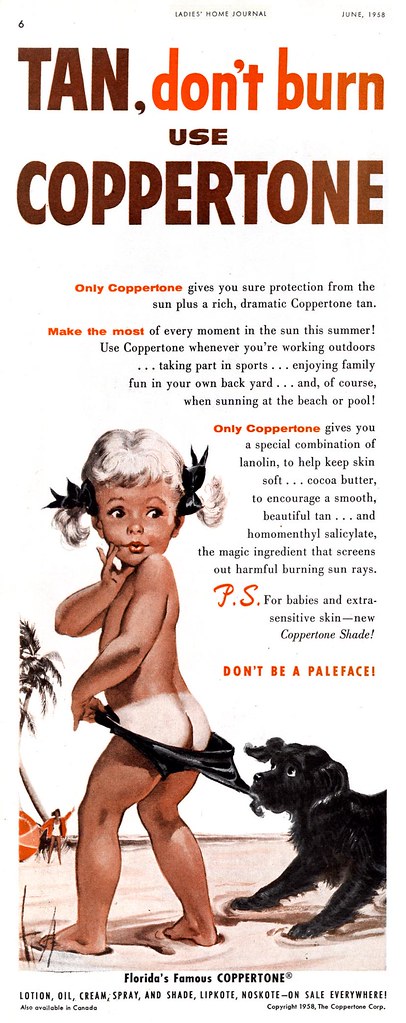

During the late 40's and well into the late 50's, hardly an issue of

Ladies Home Journal and

Good Housekeeping, the two highest profile and most widely read women's magazines, went by without story and/or advertising art by Whitmore and Whitcomb.

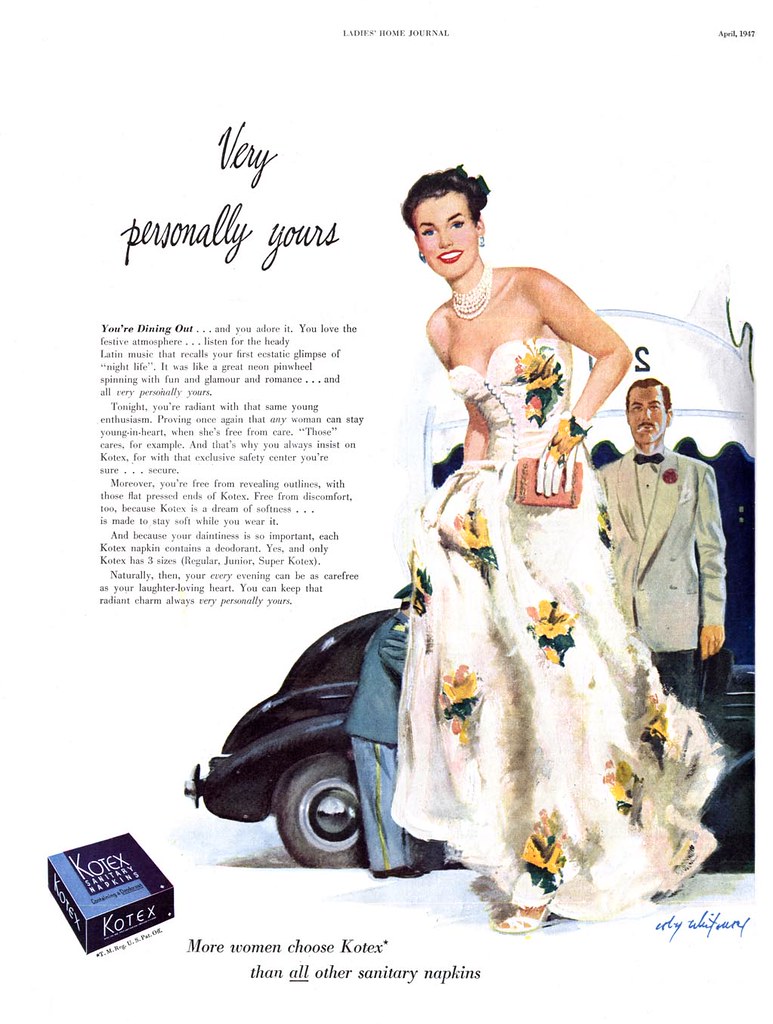

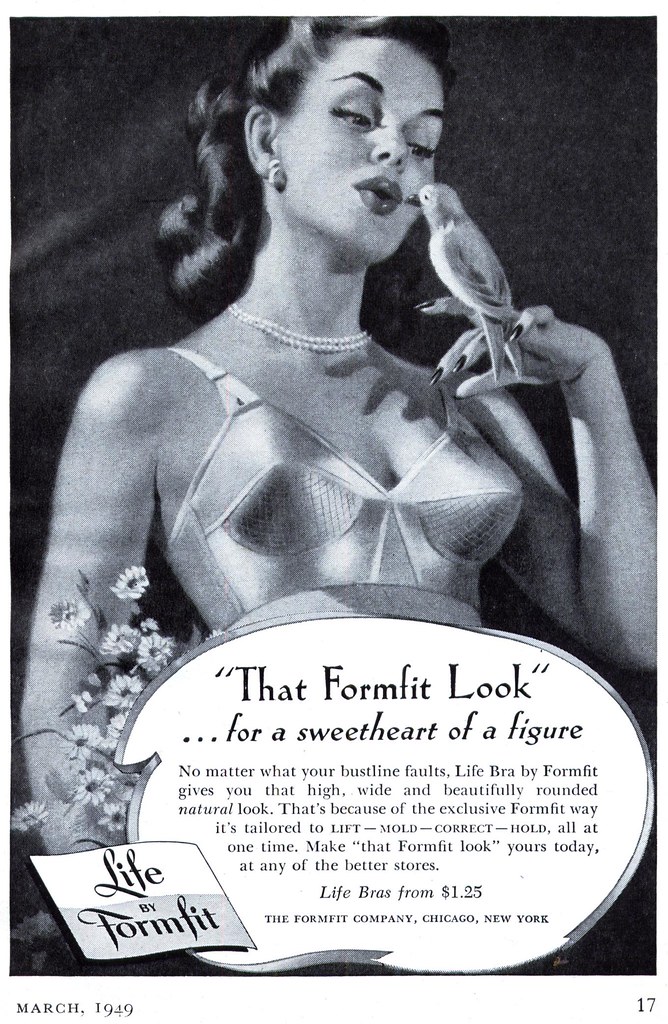

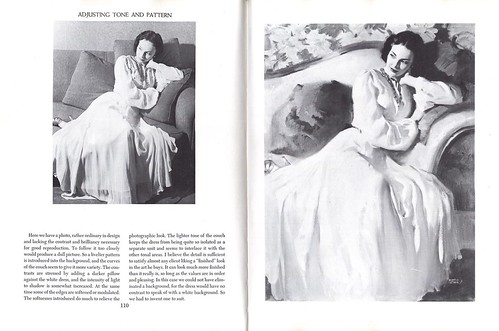

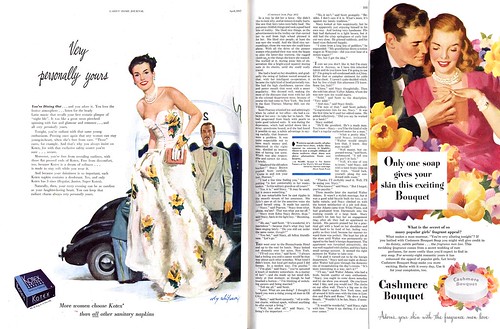

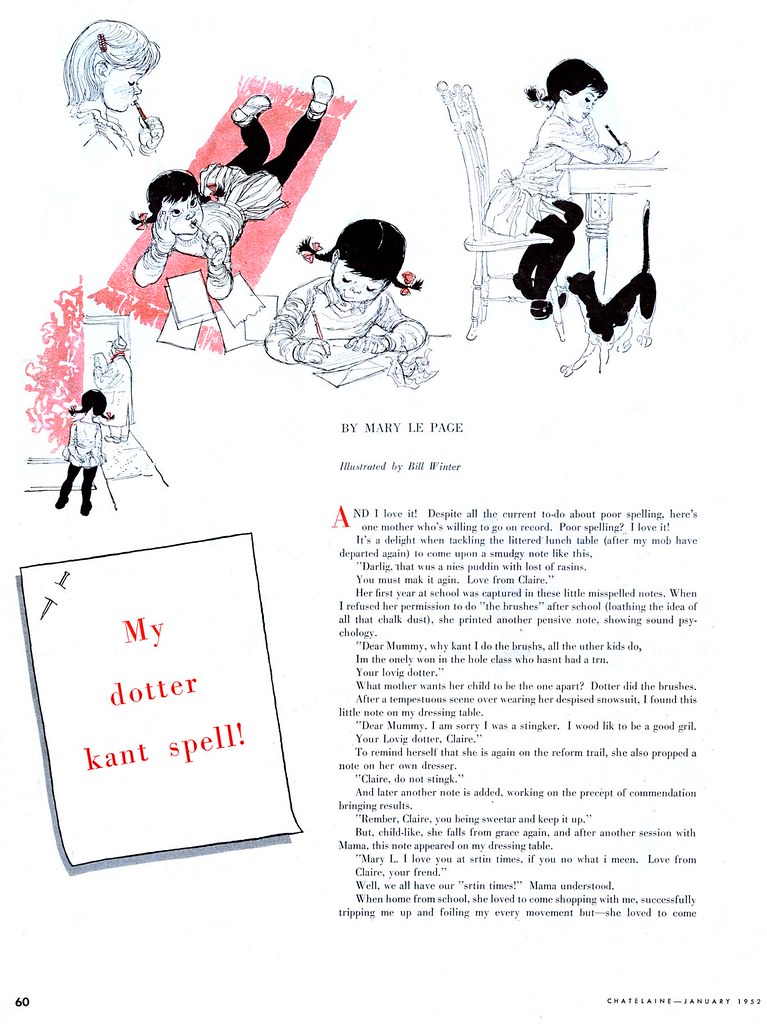

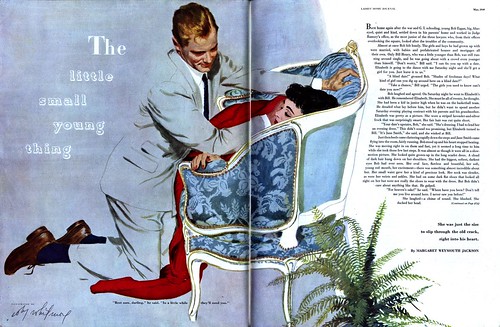

These mi-40's examples(above) still contain a sense of painterly treatment and a clearly defined, "natural" picture plane. But Whitmore's technique begins to hint at what is soon to come. He is not rendering as much "finish" -- the medium seems to no longer be oil, but perhaps watercolour or gouache. There is a sort of drybrush quality and a lack of blending that gives the work a nice vitality.

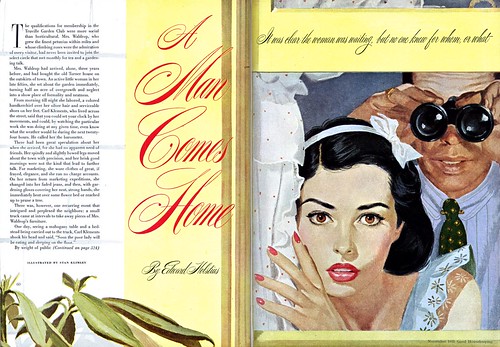

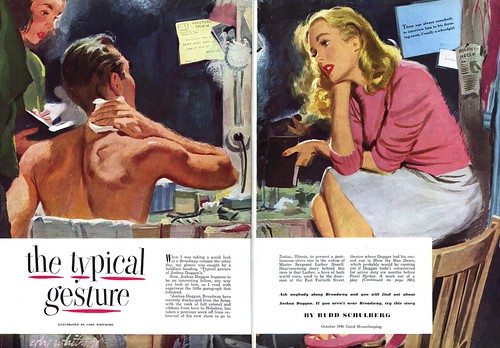

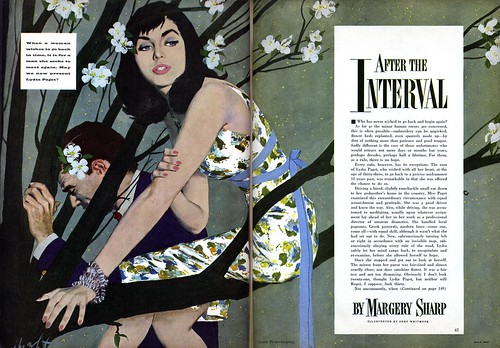

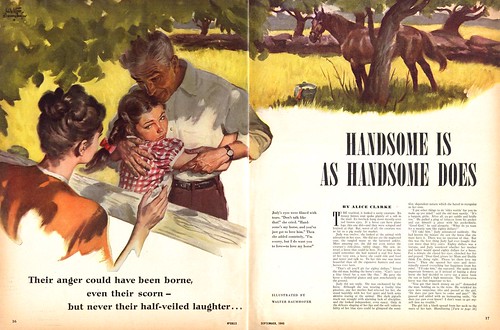

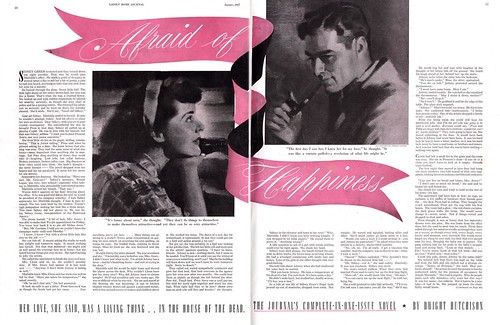

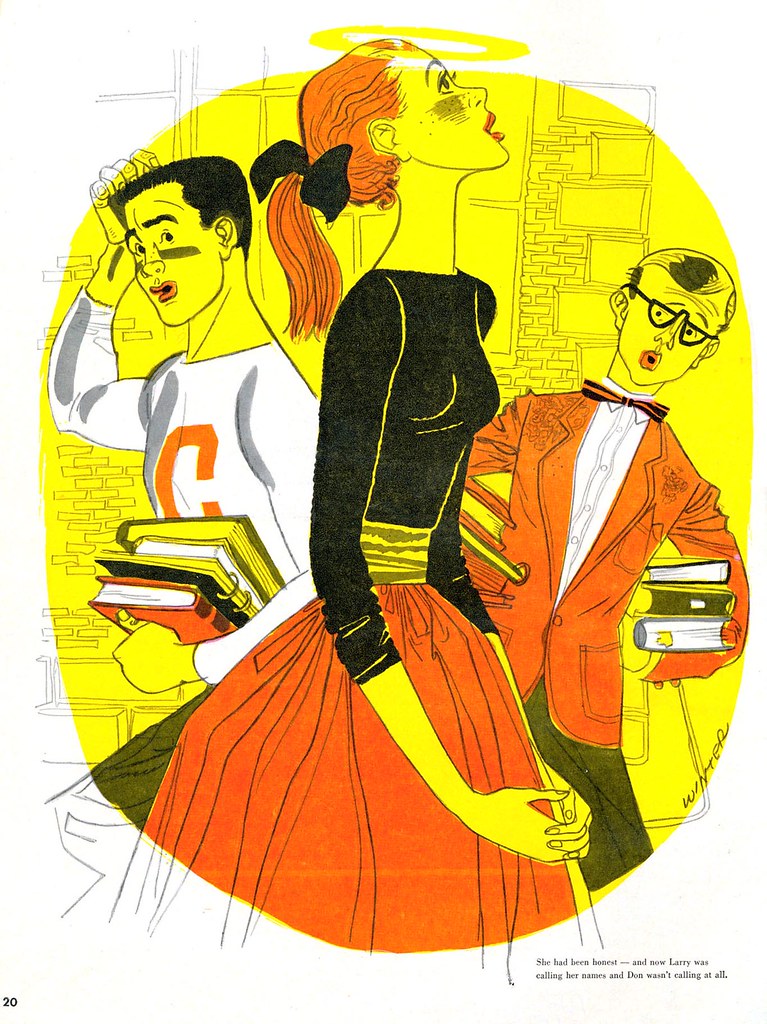

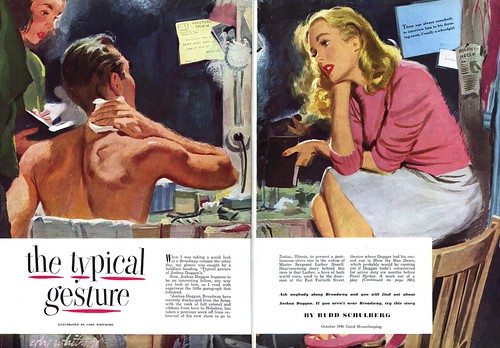

Then, in this 1949 illustration (above), we can see how the artist had begun to explore what would become typical visual cues of the New School style: background environment has been minimized or eliminated,leaving only a minimal amount of supporting props to hint at the location of the scene, the camera angle is deliberately obtuse and the figures are arranged in a visually unusual manner. Limbs, bodies and faces are partially obscured. Painting the entirety of the figure is discarded in favour of letting background and foreground blend together in an interesting arrangement of graphic shapes.

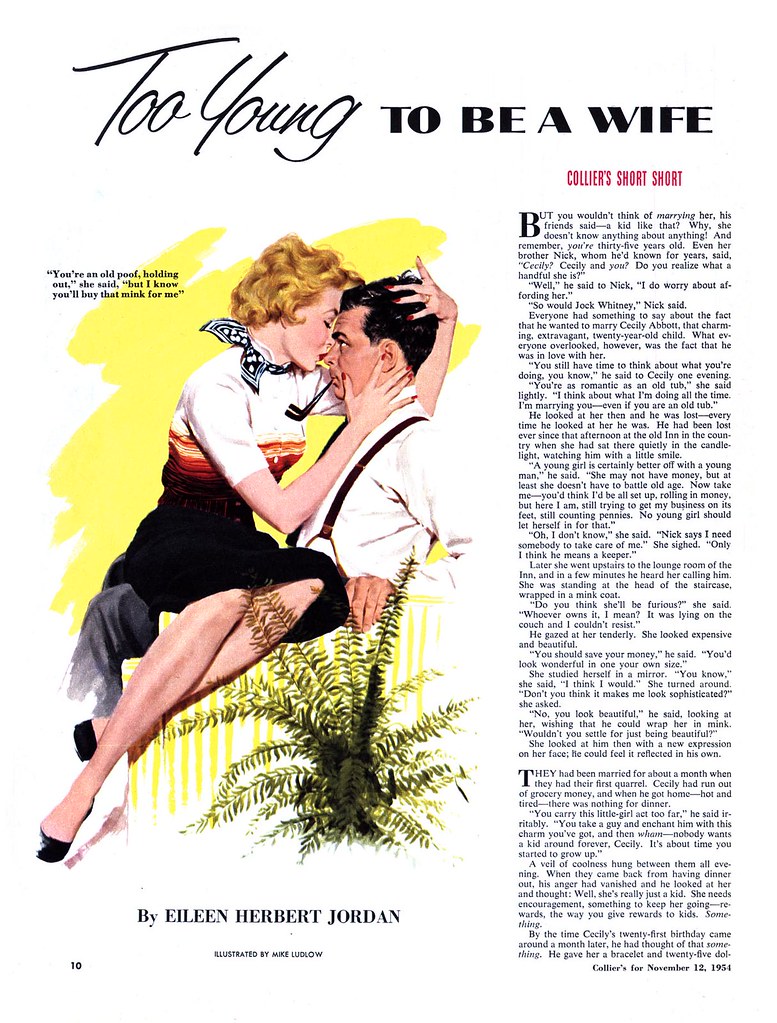

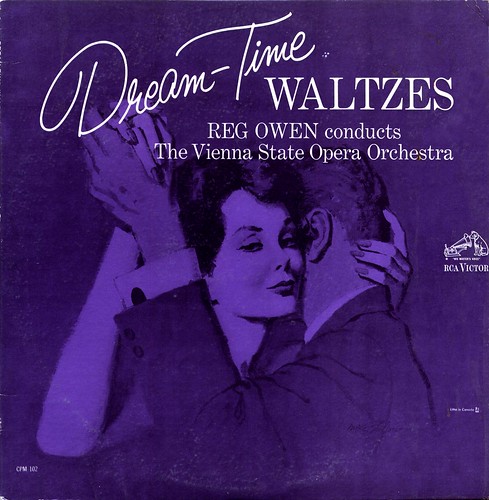

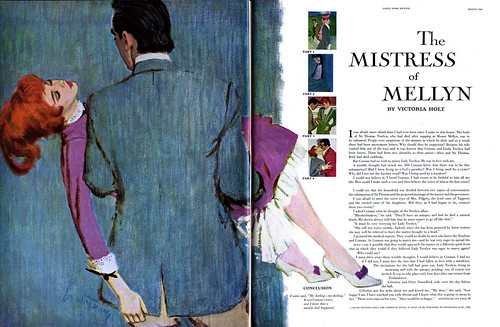

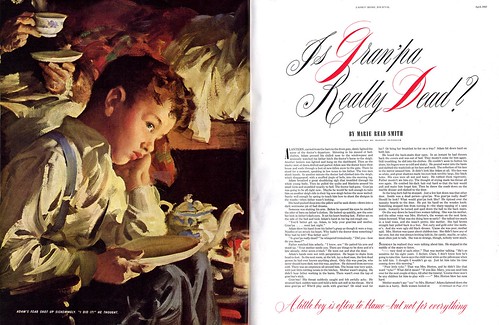

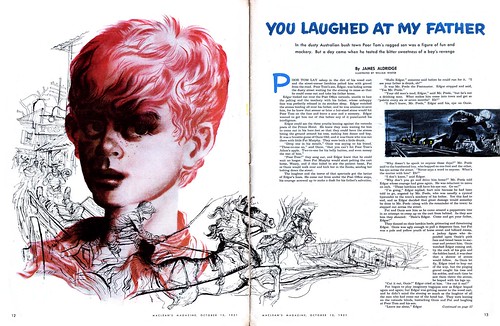

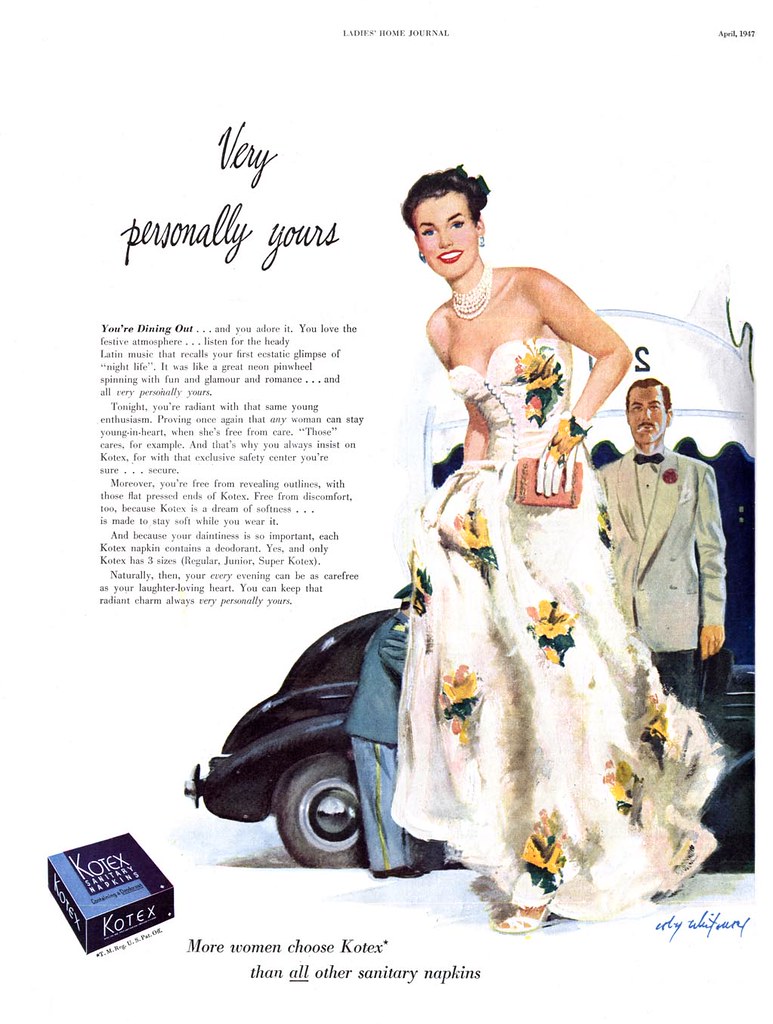

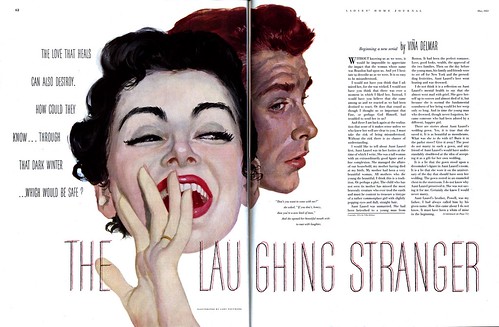

By the early 50's, Whitmore is showing us why the new School artists were sometimes referred to as "big head" artists: here he has stripped the romance illustration down to the bare essentials needed to express emotion and interaction... heads and hands and absolutely

nothing else.

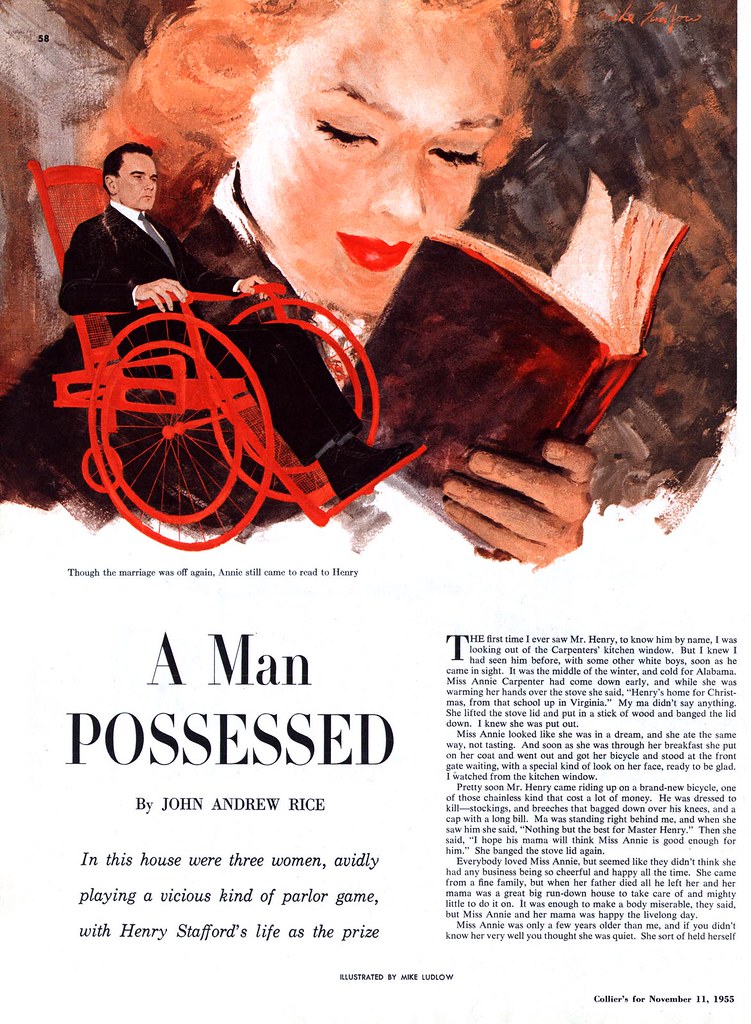

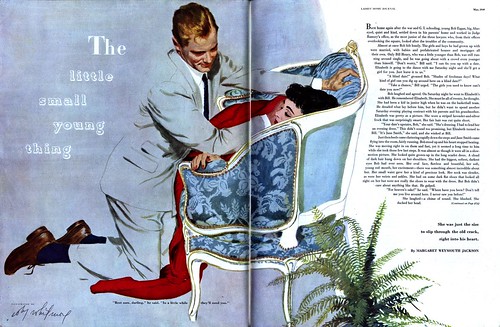

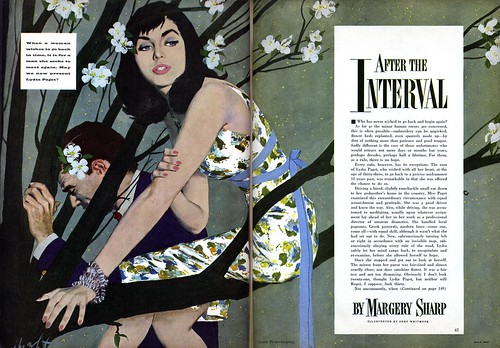

Then, during the mid-50's, what I consider to be the most visually interesting period of the New School style is displayed here with great skill by Whitmore: there are still the occassional fully or partially painted elements, usually the face and hands, and the rest is handled very graphically, with interesting patterning used to define clothing, and human and supporting environmental "props", like the flowering tree in this piece, intertwined into complex graphic shapes.

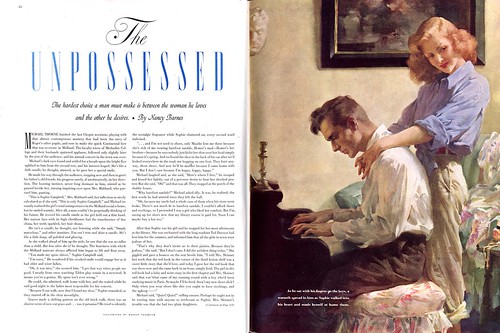

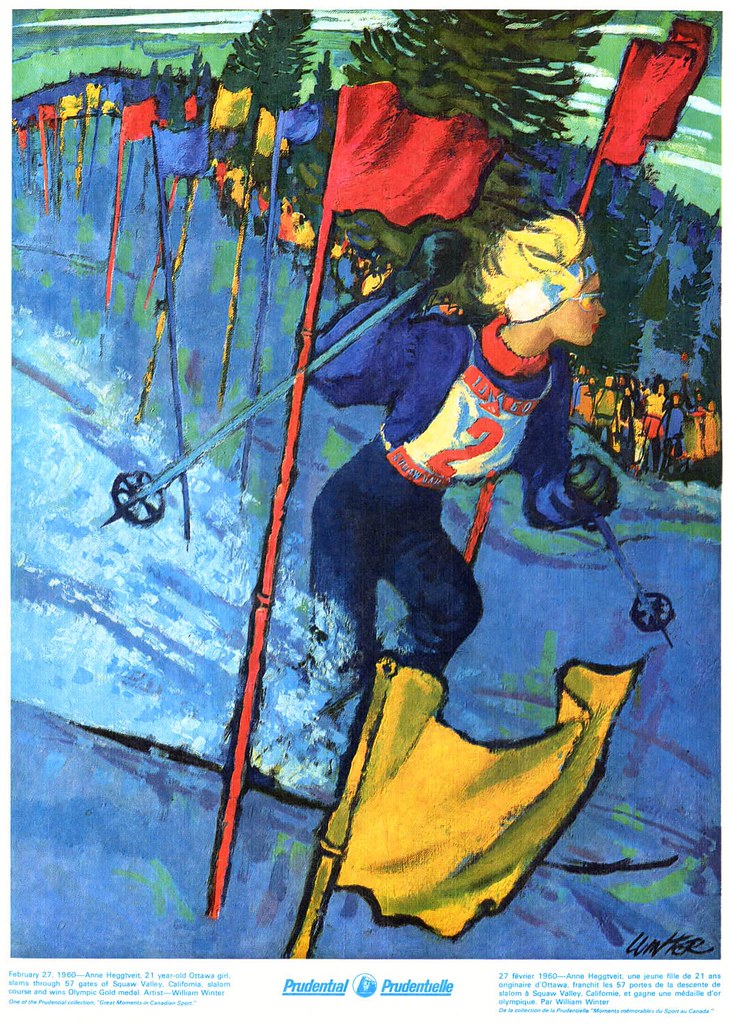

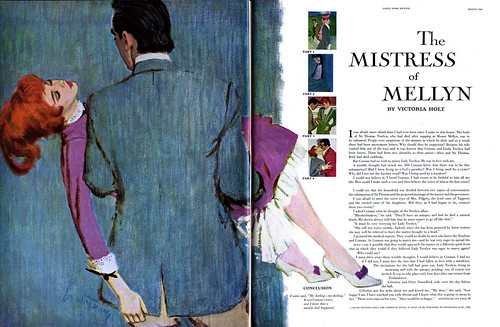

The 1960 piece below is the latest one I have by Coby Whitmore. As photography and decorative illustration styles began to dominate the magazine market, "realistic" illustrators like Whitmore evolved the New School style into a rough, sketchy phase in an effort to remain fresh. It didn't always work. In general, clients asked for less and less of this sort of work and studios like Cooper struggled to remain open.

I'm not sure what markets Coby Whitmore moved into after 1960, but with the drastic drop in magazine assignments many illustrators sought out work in the burgeoning paperback book cover business, others moved out west to participate in the lucrative "western art" gallery scene and no doubt many went into teaching. Of course there was still

some work in magazines, but the glorious days of the 1950's, when the New School dominated the printed page, were over.

We've looked at the other titans of the Cooper studio,

Jon Whitcomb,

Joe DeMers, and

Joe Bowler in the recent past, so the rest of this week I'll show you work by lesser known - though still worthy - "New Schoolers".

All of today's images have been added to my

Coby Whitmore Flickr set.