Could they have also been looking at comic book art?

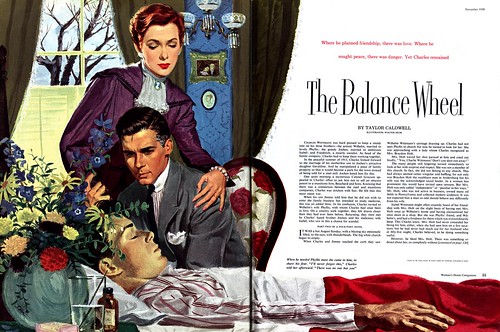

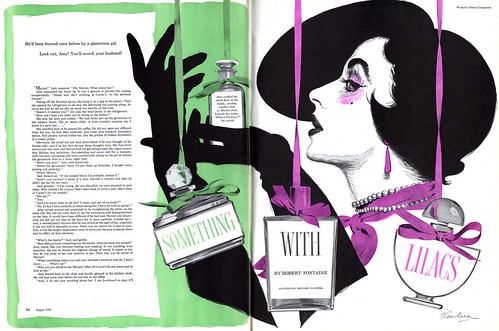

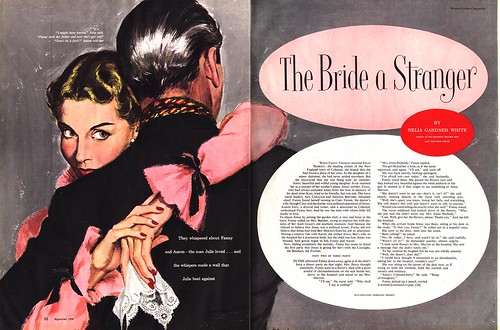

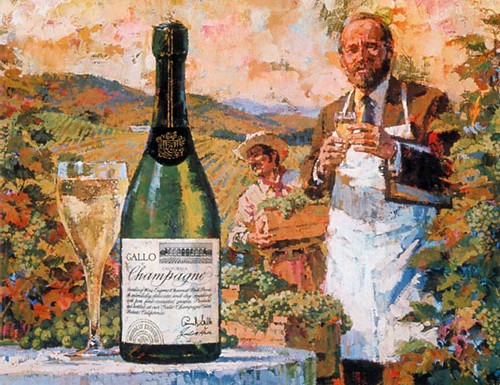

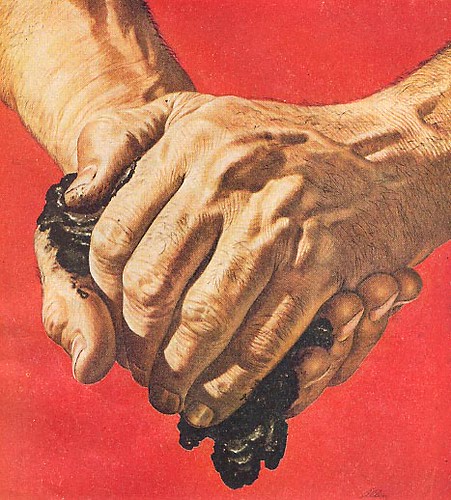

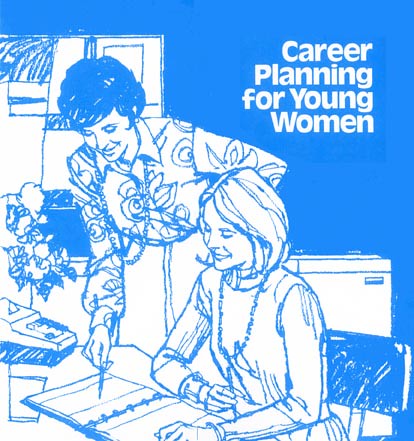

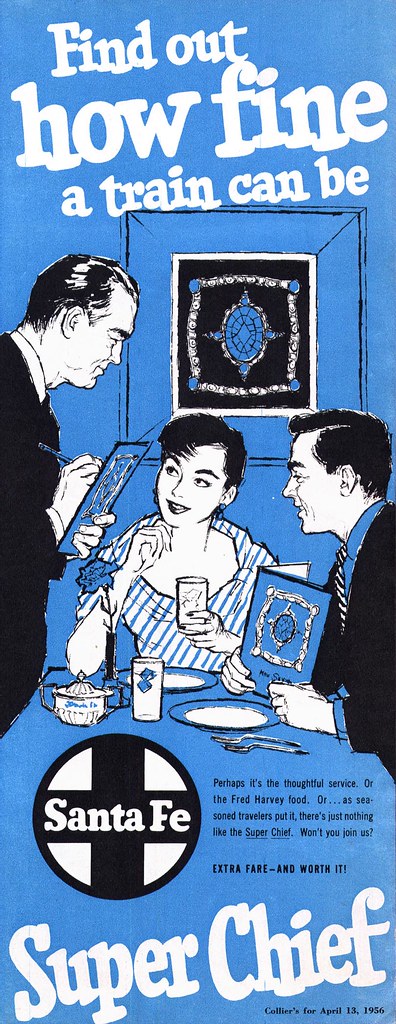

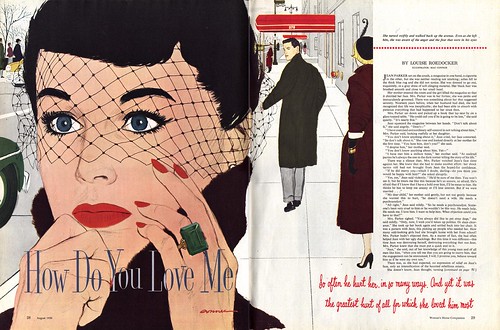

Consider this: a comic book artist working in 1950 would have had to draw many dozens of panels over 20 or 30 pages to earn a few hundred dollars. If such an artist had been working on a romance story, any one of those panels might have come out looking very much like this illustration Mac Conner created for the August 1950 issue of Woman's Home Companion. But because Conner was a highly respected illustrator working in a far more "legitimate" wing of the commercial art business, he was paid many hundreds of dollars for just this one panel.

I'm not trying to disparage Conner - far from it - but isn't it interesting that for many people the merit of artwork depends on the context in which it is presented? Many talented comic artists spent their careers toiling in sweatshop conditions, their work beneath notice - beneath contempt - to many people in the broader public. Yet flip open an old comic of the day and scrutinize any single panel and you'll likely find many a composition every bit as accomplished and lovely as the Mac Conner illustration above.

Fast forward another decade and Roy Lichtenstein's super-enlarged comic book panel paintings were selling out at the Leo Castelli gallery in New York before his first one-man show even opened. Ironically, the fine art collectors that paid dearly for Lichtenstein's paintings would have turned their noses up at the thought of framing Mac Conner's original and hanging it on their wall.

It was, after all, just an illustration.

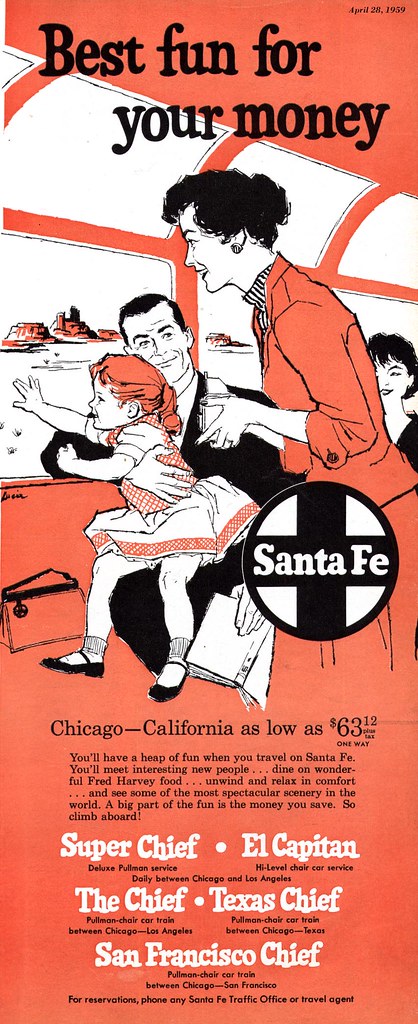

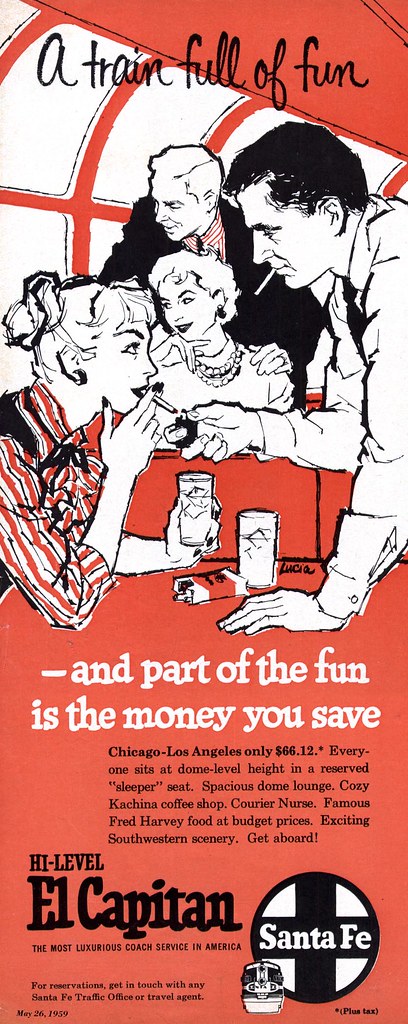

Both of these pieces and a few others can be seen at full size in my Mac Conner Flickr set.