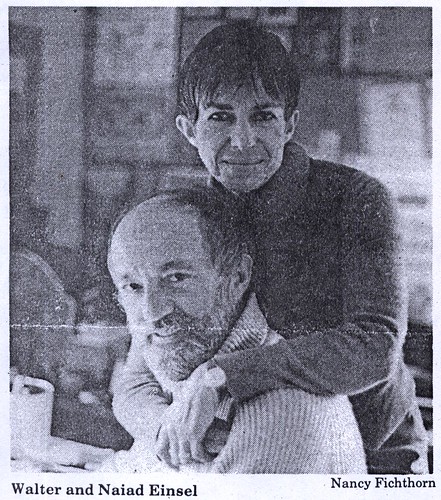

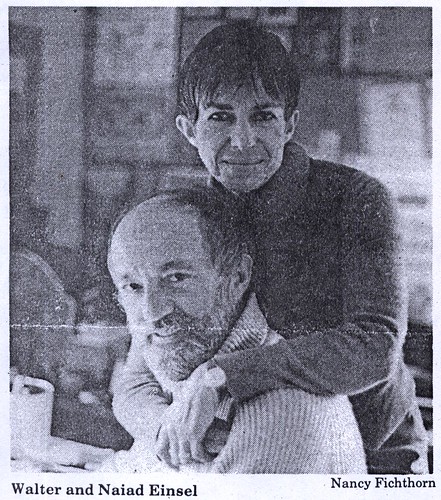

"We were really just crazy about each other," said Naiad.

"it was like a fever," Walter agreed. "It just went on for weeks and months."

"Years," said his wife, smiling across at him.

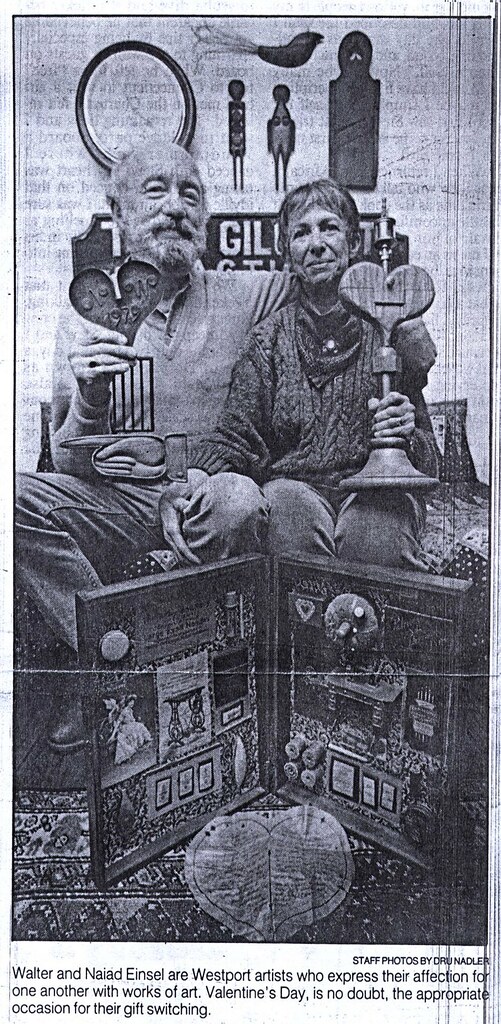

From a 1989 article in The Advocate

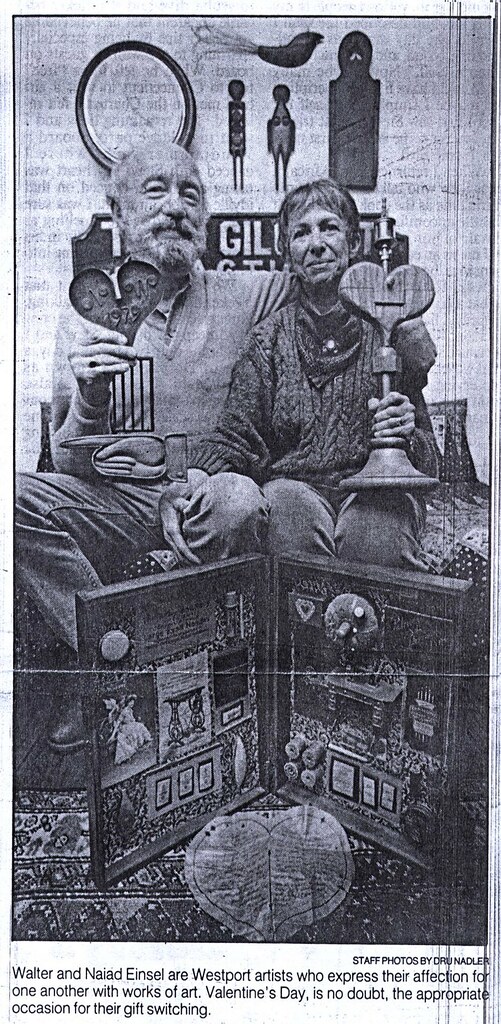

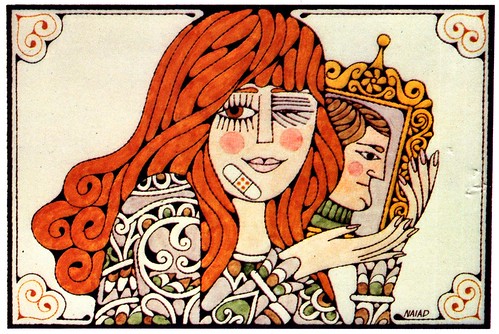

Early on in their life together, the Einsels began making elaborate Valentines for each other. It was a concrete expression of that crazy fever of love they felt for one another. When they still lived in their one room New York apartment, they would put a dividing screen in the middle of the room while they worked on them. "We were on our honour not to peek," says Naiad. Later, in their Westport farmhouse, the screen was no longer needed. Though the Einsels shared a second-floor drawing studio, their desks separated only by an old U.S. Navy map file cabinet, Walter would work on his Valentines in his sculpting studio in the barn.

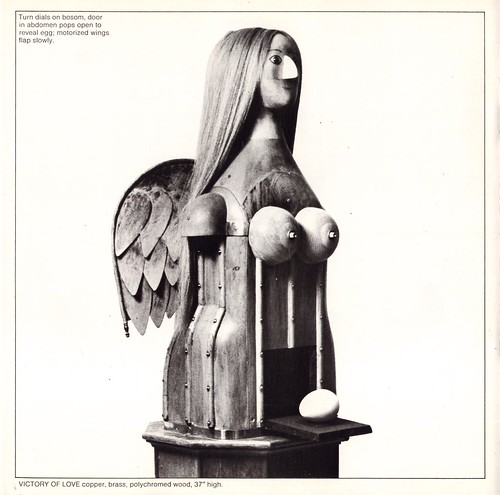

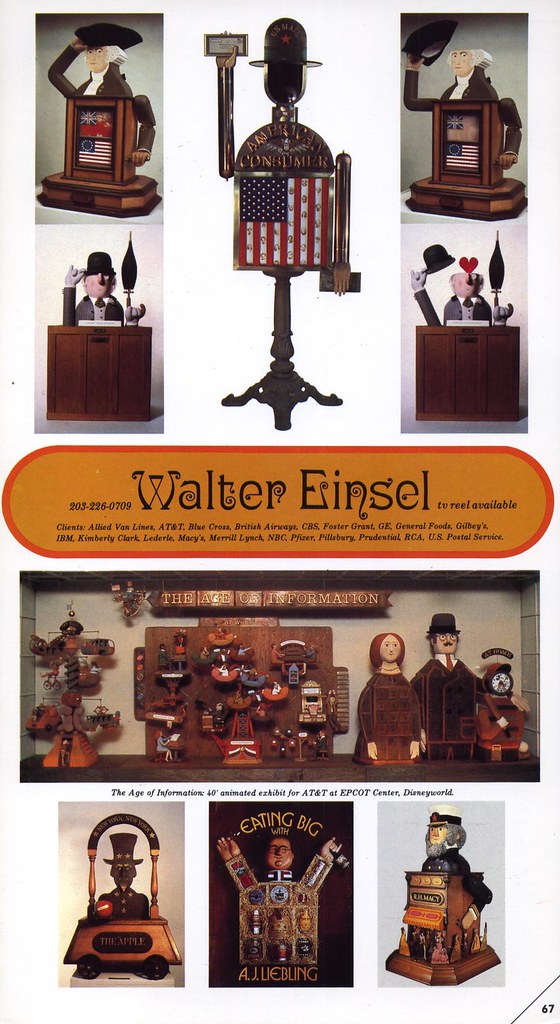

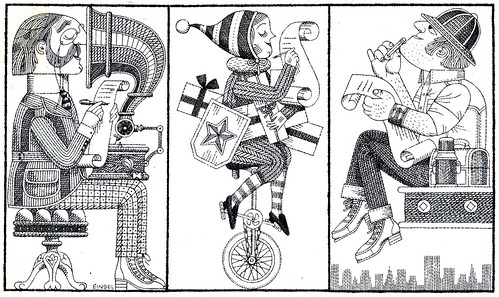

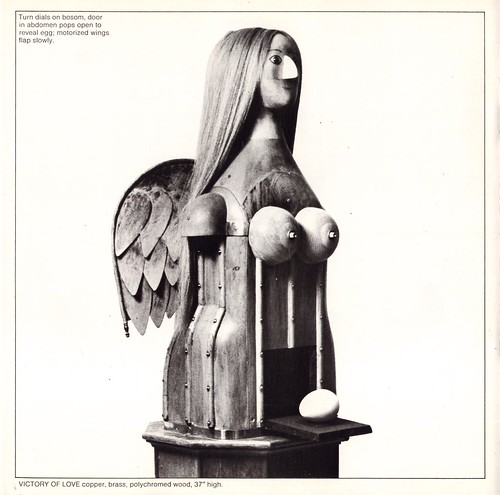

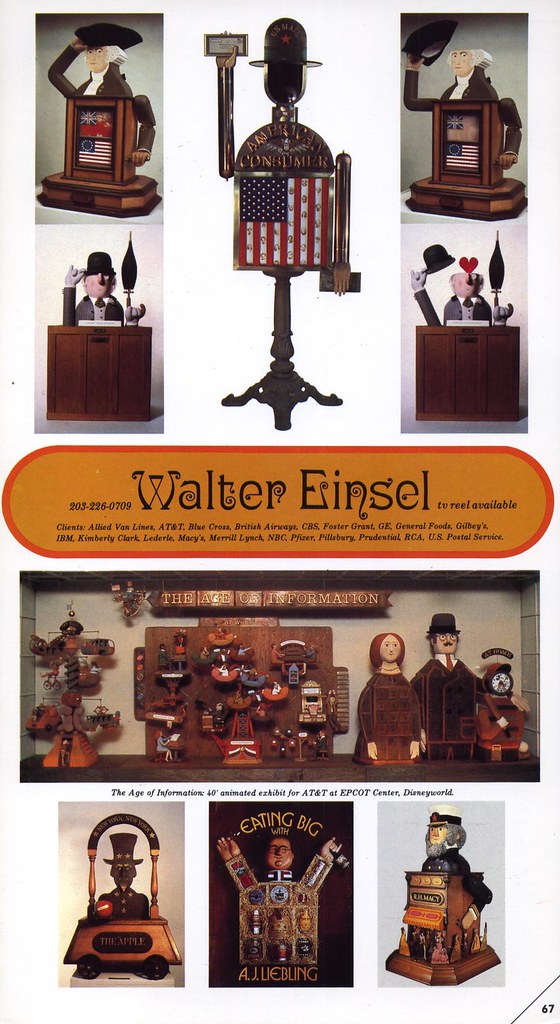

"Each year these efforts became more complex," says Naiad. What started out as collages with old decorations and rubber stamps incorporated into the design, evolved around 1960 into elaborate 3-dimensional sculptures carved in wood, with internal whirling disks and moving parts. This was a result of Walter's interest in engineering and mechanics and took his career in a new direction as he began creating Rube Goldberg-like sculptures for advertising clients in print and television.

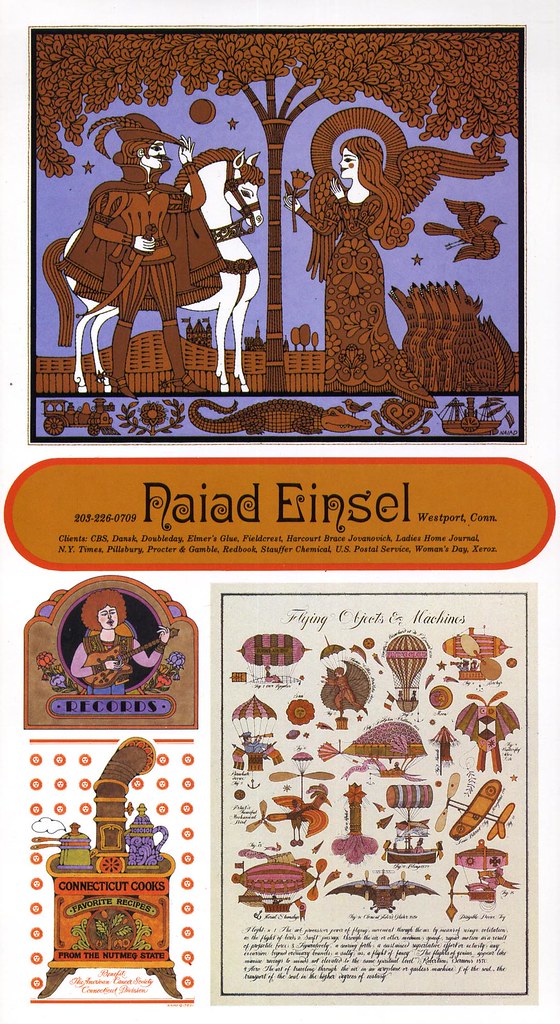

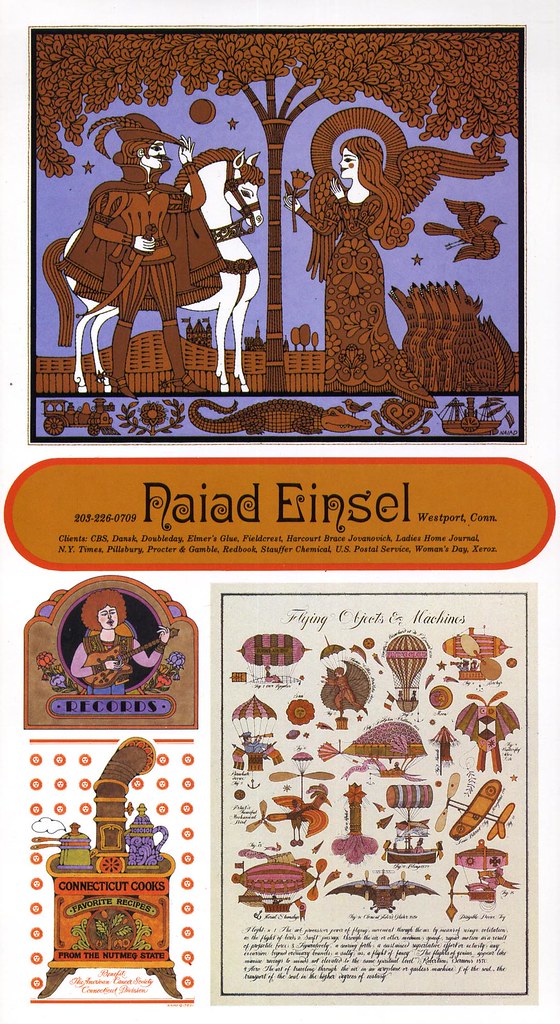

Naiad, meanwhile, was hardly resting on her laurels. Among many other prestigious accomplishments is her design and direction of the Westport Bicentennial Quilt. At 76" by 104" and with the assistance of 33 "needlewomen" to do the sewing, the quilt, begun in October, 1974 was finally put on display in January, 1976.

But in spite of their hectic work schedules, the Einsels always found the time to continue creating their Valentines. "Walter and I loved Valentine's Day. It was a big day for us. We loved it more than Christmas. We loved it more than birthdays."

Walter Einsel passed away in 1999.

"When Walter died," says Naiad, "I felt that I had been so fortunate to be a part of his life and his love. I feel very blessed. The memories of all that we had sustain me."

In tribute to those memories and that love, Naiad has been working on a book,

A Passion for Love, depicting the nearly 50 years of hand-crafted Valentines that she and her husband exchanged. "I just received some galleys on my Valentine book & I have to concentrate on them now," Naiad wrote to me yesterday as I pestered her with yet more questions.

There are so many moving examples of Naiad and Walter Einsel's tremendous love for each other, but for me, one of the most charming anecdotes is also the very first, again from the article in The Advocate: back in 1952, when Naiad was assistant art director in Promotions at CBS and Walter held the identical position at NBC. They had seen each other's work but had never met...

"I liked his work, because it looked like my own. I had this image of him with a thick German accent who was married to a big German housfrau out of Wagner," she said.

One day, a job opened up at CBS and Walter came over to apply. "I walked in and there was this adorable-looking man," said Naiad. "you know when you're young you picture this knight on a white horse..."

"I wasn't that impressed with myself," Walter interjected, "but I thought you were very attractive."

"Then we both stood there and looked at the floor," said Naiad.

To ease the tension, Walter then put his hand in his pocket and whipped out a hinged nutshell containing a miniature stage set from the opera "La Traviata".

"I thought to myself, 'Ooh, he's really weird; this is a kook...' "