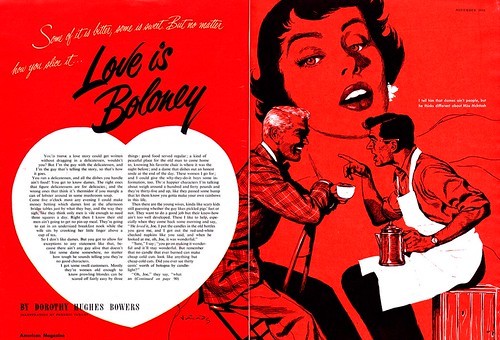

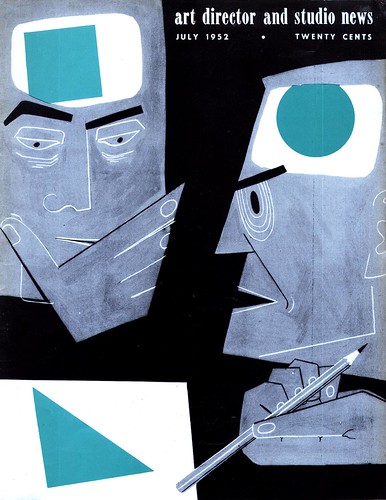

Forget New York - if you were an illustrator looking for work in 1952 the place to go was Chicago.

"It's small wonder Chicago leads the world in the art studio business," writes James A. Shanahan, Managing Director of The Association of Art Studios of Chicago in the November 1952 issue of AD&SN. "Chicago is the economic center of the United States. The U.S.A. center of population is now in Southern Illinois; the center of industry is in Northern Indiana; the center of agriculture is on the border line between Missouri and Iowa. If you describe a 500-mile radius circle around the city of Chicago, you will find within that circle's orbit:

37% of the nation's population. 34% of all the manufacturing firms producing 46% of the nation's total manufacturing output. 36% of the nation's wholesale firms. 38% of the nation's retail firms. And half of the nation's eighteen cities of more than 500,000 population."

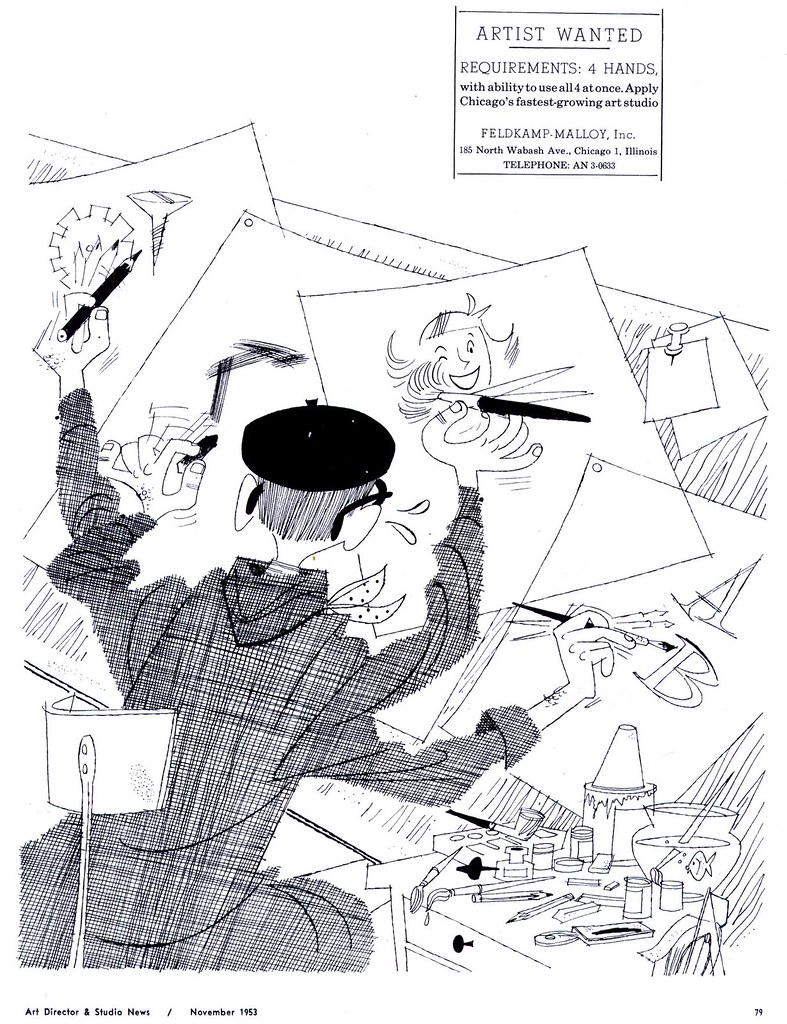

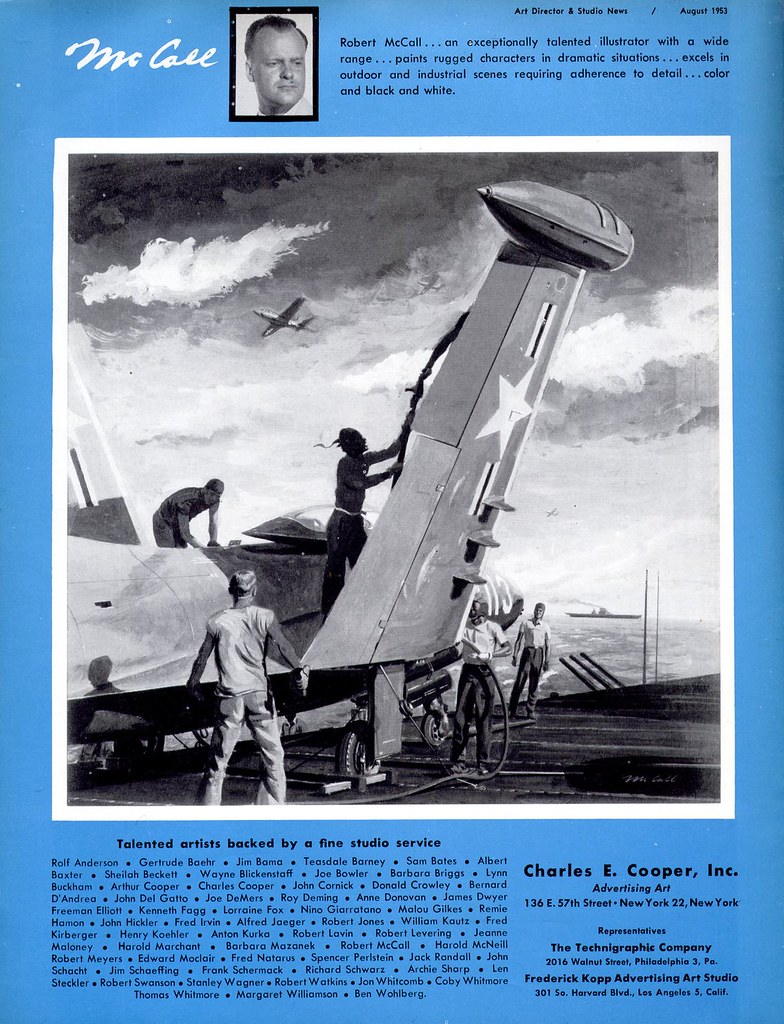

"In this great 'economic center' of the United States," Mr. Shanahan goes on to write, "there is the largest and best equipped 'art city' in the Western Hemisphere. There is no other similar area that offers the concentration of artists, designers, illustrators and photographers that is grouped together on Chicago's 'near north side'".

Chicago boasts the largest art studios in the world," says Shanahan, "some of which approach

$1,000,000 in monthly billings."

Later in that same issue, Beth Turnbull, Secretary of the Artists Guild of Chicago, writes, "Chicago is now recognized as a center of commercial art and the Artists Guild [has]

more than 600 dues-paying members."

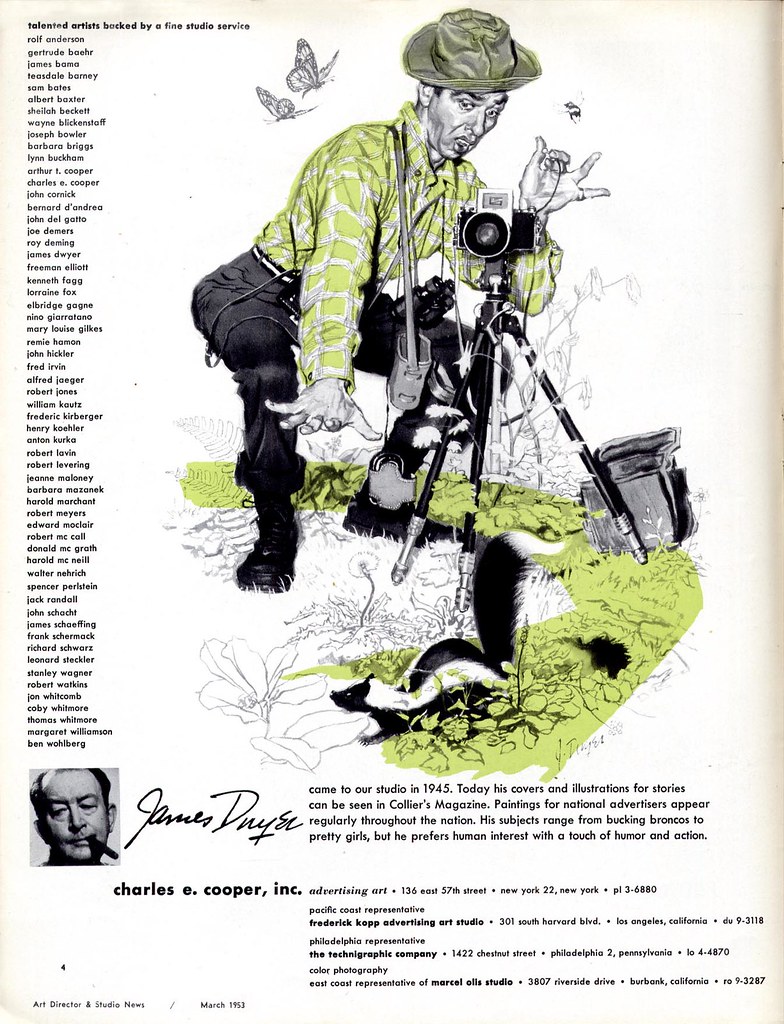

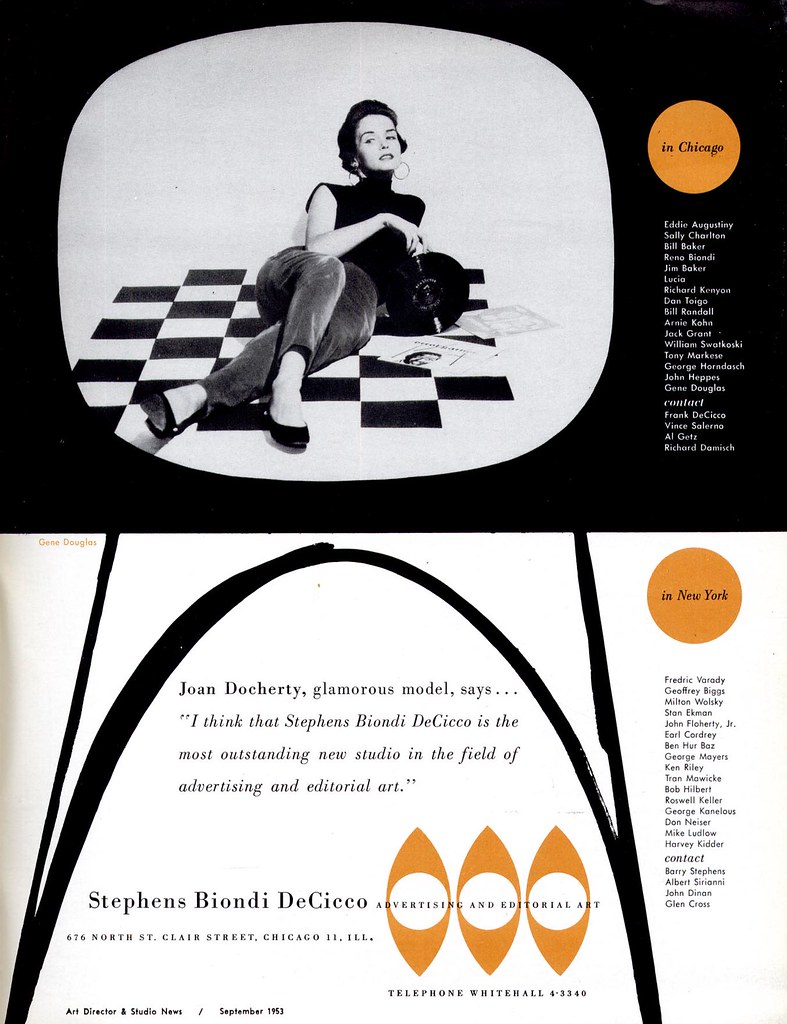

Clearly there was plenty of work for illustrators in Chicago - if rather less fame. It would seem that while the large full-service studios ruled in Chicago, the work was more often for industry, trade, packaging and display work. Few studios put much emphasis on their roster of illustrators and those that did had fewer high-profile "name" artists than did the New York studios.

Still, as James A. Shanahan writes near the end of his article, "If you had owned a certain ten Chicago art studios during July, August and September of 1951, you would have had a sales total of $1,166,553.30

for art and photography alone."