My friend and fellow in-house storyboard artist at O&M Toronto, Dan Milligan, had been asked by one of the AD's at the agency who also taught at OCAD to substitute teach her interpretive illustration class for a few weeks while she was out of the country. Because it was a large group, the AD had also asked her friend, Anita Kunz, to co-teach the class with Dan.

But when Dan and Anita presented themselves to the students for the first time, and it was suggested that half the group go with Dan and the other half go with Anita, what should have been a simple arrangement turned into a huge conflict.

Apart from a tiny handful of students, almost everyone began stampeding towards Anita.

Now you could rationalize that given the choice between a (then) unknown storyboard artist or an award winning 'celebrity' illustrator you would have rushed Anita with the rest of the group. But personally, I think something else was going on (and the comments Dan endured from the students who grudgingly joined his group in the end confirm my suspicions):

Nobody could imagine enjoying an advertising assignment. They all wanted to express their unfettered creativity - and presumed that Anita's group, doing an editorial assignment, would allow for limitless personal expression.

I believe you can trace the origin of this philosophical rift to the work of the first generation of 'Avant-gardes'... and the early adopter art directors who hired them.

Yesterday David Apatoff commented that Robert Weaver was tormented by the fact that he had had to "compromise" his creative vision by working as a an illustrator - in essence, as a 'hired gun' - and that there were some fellow illustrators who were sympathetic to that perspective.

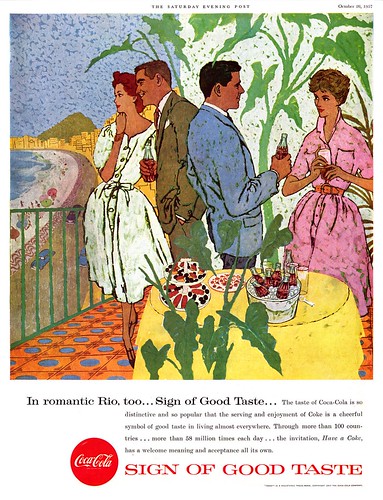

This way of looking at the profession seems to me to have been entirely alien to the previous generation of illustrators. From what I've read and from the conversations I've had with those who were there, the goal of just about every art student was to get paid to draw (not a bad prospect) and exert as much creative influence as was possible, considering the collaborative nature of the commercial art business.

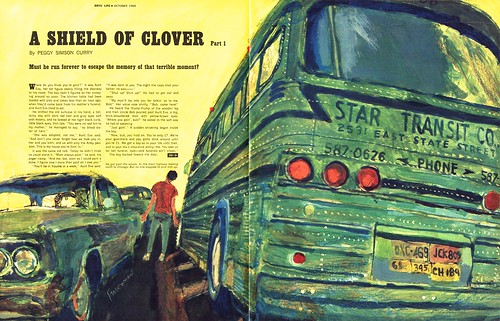

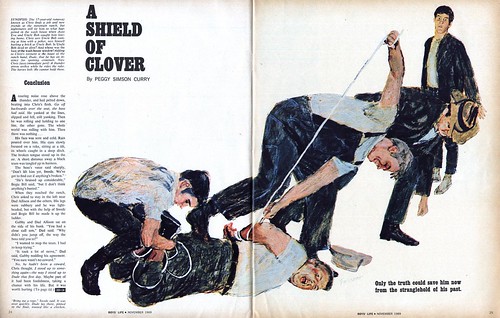

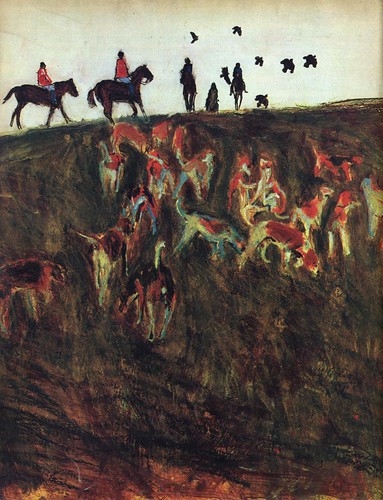

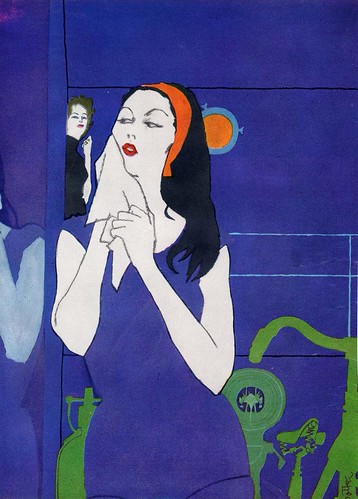

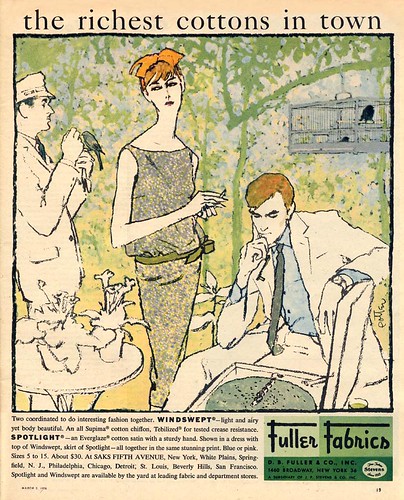

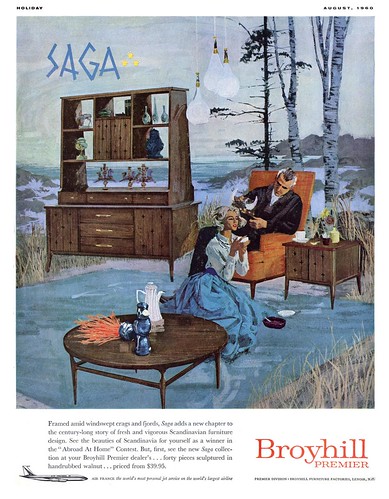

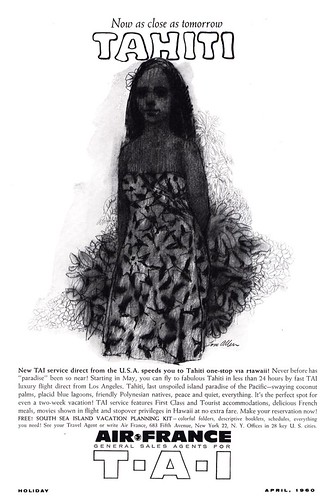

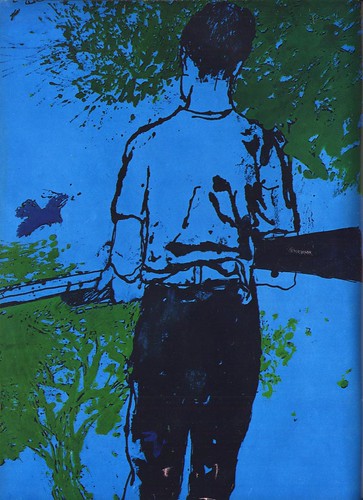

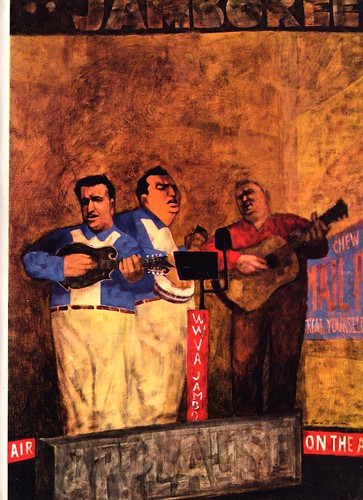

Looking at the editorial - or 'story' - art of the 50's, there is a general sense of traditional, acceptable, well-crafted restraint to the work - even when the subject matter is volatile. Even the most forward thinking illustrators like Al Parker seemed to have set certain parameters... certain boundaries that simply could not be crossed.

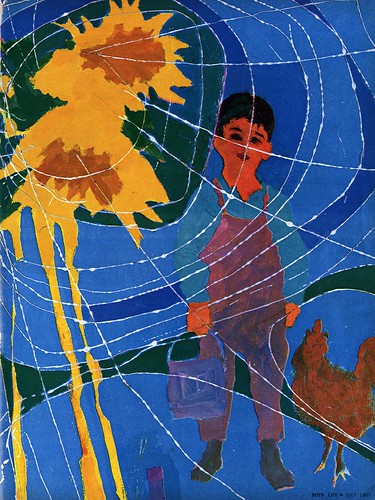

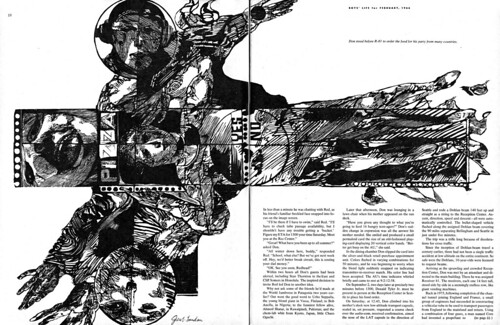

But beginning with the Avant-gardes - and I would say continuing to this very day, the idea of having total creative freedom (and I'm going to go out on a limb and suggest, even freedom from the constraints of craft) has been seen by a faction within the illustration business as a more acceptable - and even nobler - attitude than the traditional approach to commercial art.

I'm hardly in a position to judge. Like I said at the beginning of the week, I like a lot of the work we're looking at in these posts, even though I have to admit that I don't neccessarily understand it. But in regards to the broader public (and ultimately, we are talking about work produced for consumtion by the general public), no doubt some would say, "why would I want to pay somebody all that money for something my 5-year-old could draw?"

Is this were unfettered creativity leads? And if so, how does it make for viable commercial art?

This post will be continued... tomorrow.